Here’s a new climate change reality that Trump’s new policies ignore

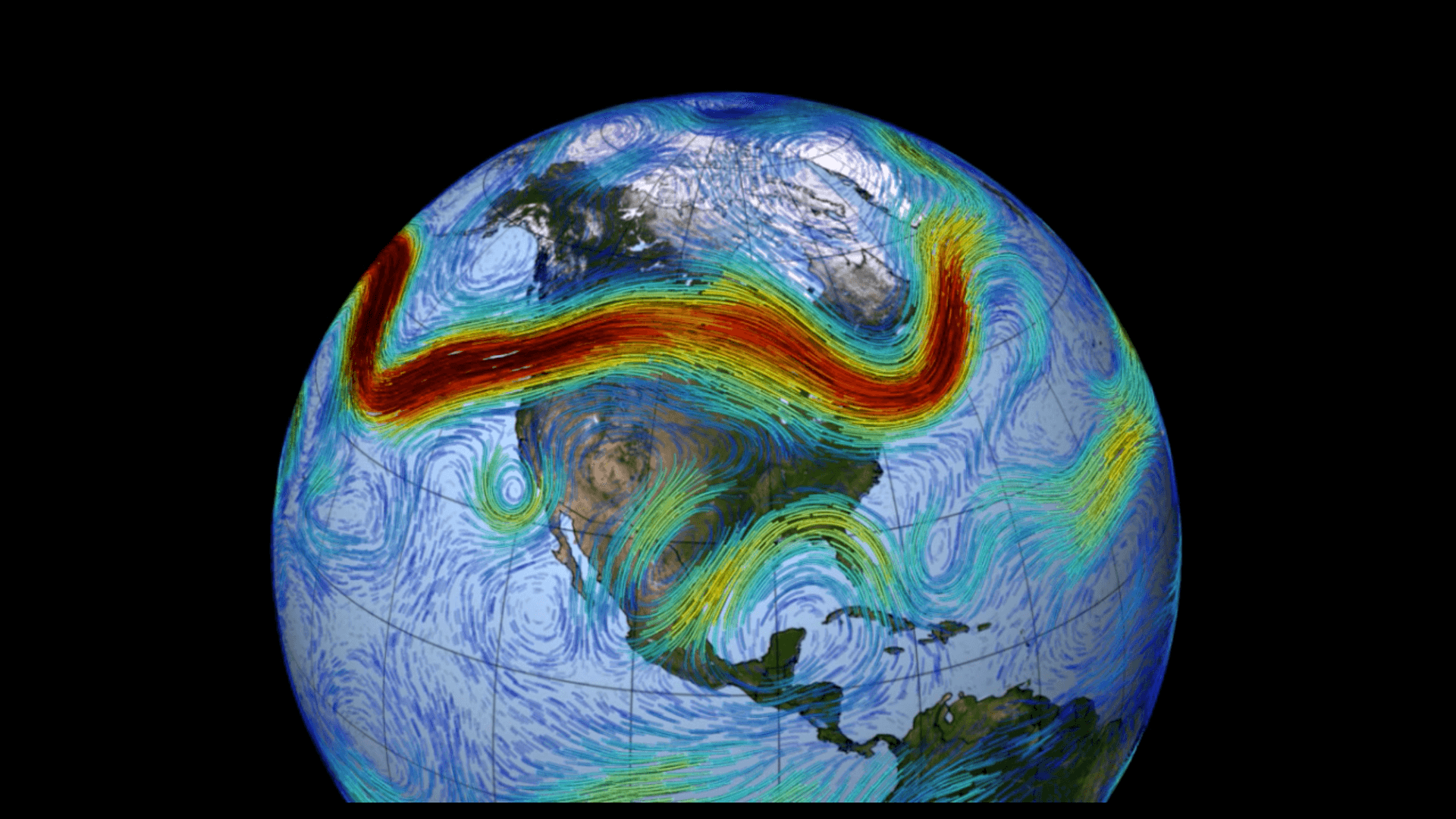

The Polar jet stream carries weather systems around the northern hemisphere. New research finds that warming in the atmosphere due to carbon pollution is disrupting its flow and contributing to dangerous extreme weather events.

President Donald Trump may be trying to scrub his predecessor's initiatives to fight climate change from just about every corner of the federal government — Exhibit A being this week’s executive order aimed at undoing Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan — but the reality of the climate crisis is not going away.

And the dangers we're facing may have gotten even clearer this week with a new study confirming a strong link between a warming atmosphere caused by human pollution and a growing wave of extreme weather events around the world.

The study, by veteran climate researcher Michael Mann at Penn State University and colleagues in the US and Europe, may nail down a phenomenon hinted at for several years: that rapid warming in the Arctic is disrupting the Northern Hemisphere's jet stream, which in turn is causing weather systems to slow down, turning rainstorms into extended deluges, hot days into heat waves, and dry spells into droughts.

We already knew there was a relationship between climate change and certain types of extreme weather events, Mann says. But he says the new study, published this week in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, shows what he calls “an extra linkage” in the effect of rising temperatures on the northern jet stream.

Rapid Arctic warming brings a slow and loopy jet stream

The jet stream is that ribbon of winds in the atmosphere that you see represented on your local weather report that carries storm systems across the Northern Hemisphere. And crucially, Mann says, “it owes its existence to variations in temperature with latitude — the colder it is at the poles, and the warmer it is at the equator, the stronger the jet stream.”

But those variations are starting to shrink, because the Arctic is warming up much faster than the rest of the planet.

That decreases the contrast between the Arctic and regions farther south, Mann says, which in turn decreases the strength of the jet stream. “And it turns out, our study shows, that it also creates conditions where the jet stream is likely to get stuck in place for long periods of time, and it's likely to exhibit very large meanders — those north and south wiggles that you see when you look at a weather map.”

The larger those wiggles, Mann says, the more extreme the regional weather becomes.

Mann says his and his colleagues’ work established clear links between this disruption of the jet stream and extreme weather events like the 2015 California wildfires, a massive 2010 heat wave that destroyed more than 30,000 square miles of crops in Russia, extreme flooding in Pakistan the same year that killed nearly 2,000 people, and a 2011 heat wave and drought that led to a widespread loss of cattle in Texas.

And he says in general, these types of impacts are likely to increase further as the temperature barrier around the Arctic weakens and the jet stream slows and meanders more.

“When we get what we think of as extreme weather, it isn’t so much something happens one day but that you have a low-pressure system that’s just stuck in place, continuing to produce rain over the same region for days at a time,” Mann says. Or “there’s someplace else where the bend in the jet stream is causing very hot conditions, and if those conditions persist you get extreme drought.”

Trump policy vs. climate science

Mann’s research focuses on the science of climate change. The irony of the timing of this finding’s release isn’t lost on him.

“It's somewhat jarring — the day after our study appears we hear that the Trump administration basically wants to eradicate the Clean Power Plan,” Mann says.

The CPP was the cornerstone of Obama’s commitment to meet the US pollution reduction targets under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, adopted by nearly all of the world’s countries. It would force electric utilities to dramatically cut pollution from power plants, with the heaviest burden falling on those powered by coal, the dirtiest of fossil fuels.

Related: Trump is ending Obama-era emissions cuts. How will CO2 emissions change?

The Clean Power Plan has been tied up in court and has not yet gone into effect. Trump’s order likely will result in the US dropping its effort to put the plan in place, but that move could itself face court fights from supporters of the CPP.

But the president’s order will certainly reverse a host of other climate-protection policies across the federal government. And Mann says the message to the rest of the world is clear: “What you have here is a situation where the US looks like they are retreating from participation in global efforts to conquer this problem.”

And he says that makes it more difficult for the whole world to beat back the climate crisis.

Mann is also deeply concerned about proposed cuts to federal funding for climate research, including work like his, that helps us understand what we’re doing to the planet and what might lie ahead.

“The problem apparently is that they just want to stop research that might be inconvenient to them and the fossil fuel interests that are running the show,” Mann says. “Clearly they are trying to simply dampen the message by preventing the messengers from even doing the work to understand climate change. And that is really scary.

“This harkens back to the days of the Soviet Union, where under the Stalin regime they tried to criminalize science that didn't support their ideological viewpoints. And it now feels like that's what's happening here in the US. There's an effort to stifle research, and an effort to defund climate research — at NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration], at EPA, and probably we will see that at the National Science Foundation as well, which is the main funder of basic climate research.”

If that happens, Mann says, “it would affect every climate scientist that I know in this country.”

See also:

Former UN climate chief: Trump's energy order not 'a big deal' for climate agreement

Two US coal miners, two very different perspectives on the future of coal