Scientists just used Hawaii as a ‘body double’ for Mars

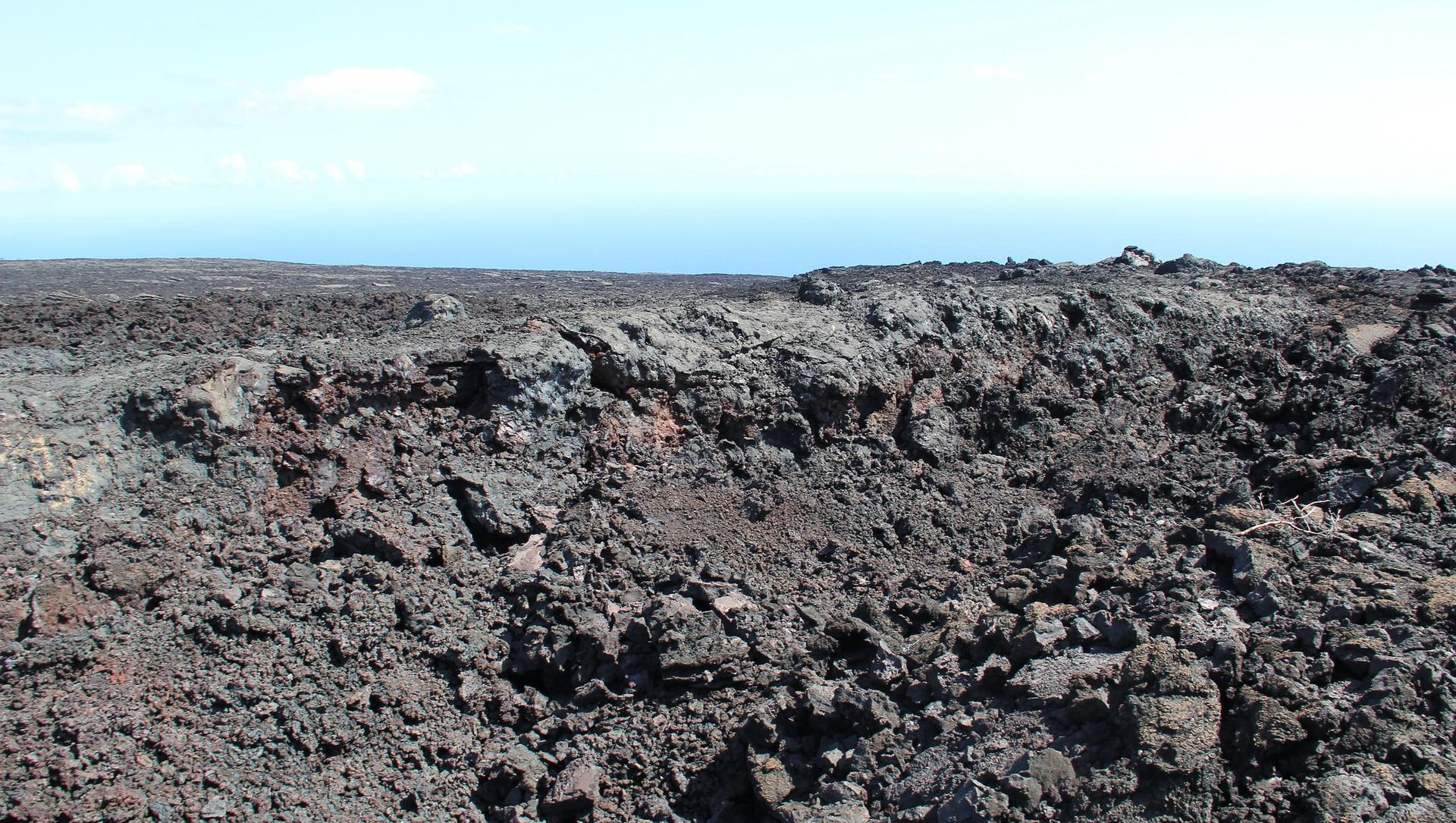

This is Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, which, in many ways, simulates a young Mars.

This fall, there's been plenty of buzz about sending humans to Mars. Elon Musk recently unveiled designs for a two-stage Mars vehicle and NASA has its own transport system in the works, slated for launch by the 2030s.

But how will scientists (and the rest of us) get to the Red Planet, and how will science actually happen once we're there?

To answer those questions, NASA’s BASALT mission — a snappy acronym for “Biologic Analog Science Associated with Lava Terrains” — recently simulated Mars fieldwork in an unlikely spot: Hawaii.

“This part of Hawaii is not the palm trees and the white sandy beaches that you might see on the postcards,” says Christopher Intagliata, Science Friday’s senior producer.

In fact, it’s downright hostile. Intagliata visited researchers at BASALT base camp, near the Mauna Ulu volcano in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park. There, the landscape oozes steaming lava. “There's even a bubbling lava lake up the road, with bubbles as big as Volkswagens exploding and splashing lava,” Intagliata says.

As it turns out, this section of the big island, Hawaii, is roughly analogous to what Mars was like in its youth, 3 billion years ago. “It's pretty wet, and there's all this activity, so that's why NASA … picked it as a simulated area for a Mars mission,” Intagliata says.

The BASALT team’s deployment in Hawaii wrapped up on Nov. 18. BASALT also spent part of August at Idaho’s aptly named Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve. One of the main goals of their fieldwork was to figure out how human scientists could safely and efficiently conduct research on Mars. BASALT researcher Rick Elphic, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, told Intagliata scientists on Mars will need well-thought-out protocols.

“You know, a scientist can easily get caught up in the, ‘Oh, that’s cool,’ ‘That’s pretty,’ ‘That’s something I’d like to investigate and explore,’” he says. “And if you don't have the time to do it before your oxygen runs out, well, that's dumb.”

Each day, the BASALT astronauts conducted their fieldwork at a sample site, directed by an operations team of scientists, programmers and engineers back at the park’s Kilauea Military Camp.

At each sample site, Intagliata says, the scientists did things like collect geologic samples, take pictures and zap rocks with X-ray machines and spectrometers. It was all part of figuring out the kind of tools that would be useful on Mars, he adds. “What sort of instrument or X-ray gun would a real astronaut want to be carrying around in the field pack? What's the geologic tricorder that they would want to develop for that sort of trip?”

And to make the mission as lifelike as possible, the astronauts even communicated with "mission control" at the camp using simulated Mars communication delays. Darlene Lim, BASALT’s principal investigator, told Intagliata that the delays will be a challenge to conducting research on Mars. “How do you allow … data to come into a science team that is effectively, you know, hundreds of millions of miles away, as well as separated by a delay in the communication?”

In all, Intagliata says, the distance between Earth and Mars can translate to a communication lag of four to 24 minutes each way — a far cry from the one-second delay shouldered during the Apollo missions. This means that when scientists do make it to Mars, they’ll effectively be working in the future. The lag, he says, “is kind of reimagining mission control.

“They’re going to have to figure out, ‘How do I help these astronauts that are walking around on the surface, knowing that they’re actually in the future for me, and everything that I’m getting is past information?’” Intagliata says.

For all the meticulous detail in BASALT's Hawaiian simulation of science and communication of Mars, there was just one thing missing. For Lim, it came up every time she explained the mission to an agreeable bystander: "Do you have spacesuits?"

The BASALT team didn't, but, "I think that visually, people just imagine that you have to have spacesuits," she says.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!