How a secret US war created a new generation of Americans who changed foreign policy

President Obama has pledged $90 million dollars over three years to help remove unexploded US bombs that still kill and maim people in Laos today.

Farmers in Laos saw small balls falling like toys from planes in the sky. Some exploded. Others just lodged in the ground. They called them “bombies.” After nine years, one-third of their small country had a bombie on it.

“As one Laotian said, the bombs fell like rain,” President Barack Obama said in a visit to Laos earlier this month. “I realize that having a US president in Laos would’ve once been unimaginable. Six decades ago, this country fell into civil war, and as the fighting raged next door in Vietnam, your neighbors and foreign powers, including the United States, intervened here. As a result of that conflict and its aftermath, many people fled or were driven from their homes."

For the first time, an American president admitted that his country dropped those bombs, and as a result innocent people became refugees. Obama didn’t apologize. But he explained why the US made bombs rain from the sky — more bombs than the US dropped on Germany and Japan during World War II.

“At the time the US government did not acknowledge America’s role," Obama said. "It was a secret war. And for years the American people did not know. Even now, many Americans are not aware of this chapter in our history and it’s important that we remember it today.”

Obama announced he was doubling US funding to $90 million over three years for removing unexploded bombs that still kill and maim people.

So when did the US change from a country that wouldn’t admit it dropped the bombs, to one that accepts responsibility and makes things right? One possible answer: when Laotians became Americans.

"You bombed our country, therefore we had to leave it and come here and we became part of you," explains Phitsamay Uy, a professor of education at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. "You educated us to know what our civic duties are. And this is how we contribute back. To make America great again, we're going to make America accountable for the actions they've done.”

Laos’s only crime was that it was next to Vietnam. The US thought Viet Cong soldiers, who fought the US and South Vietnam, were hiding there. Laos was supposed to be neutral under an international agreement, so the bombings had to be secret.

In Laos though, the bombings created chaos that fueled civil war. Uy was four-years-old when her father left Laos with her brothers. Her mother took Uy and her sisters out of the country by boat.

“She bribed a cargo captain and he put us into this pickle barrels in the middle of the night," Uy says. "And she made it all like a game. Like ‘OK you be quiet. We'll see who's going to be the quietest.’”

They were placed first in a state prison and then, when space opened up, a refugee camp. Two years passed. One day an American colonel visiting the camp recognized Uy's father. They had worked together; Uy's father had helped Americans gather intelligence about Viet Cong supply lines. The colonel helped Uy's family come to the US.

She didn’t know that her story actual began with her adopted country secretly bombing her homeland. Uy didn’t know about that until she went to college and got an assignment to interview her mother about how they came to the US.

“I'm just like, 'Oh my god, why hasn't anyone told me this before?'" Uy recalls. "And what I realized later is when communities have trauma — you have this post-traumatic stress disorder where you don't want to say too much because it might trigger you. And so my mom, and a lot of our elders, had this culture of silence because they don't want to talk about that stuff. Because, you know, it could be harmful.“

A few years later, Uy was working as a teacher in the Boston area when a woman from the Ford Foundation visited her school. Channapha Khamvongsa was working on a project to identify and connect refugee communities.

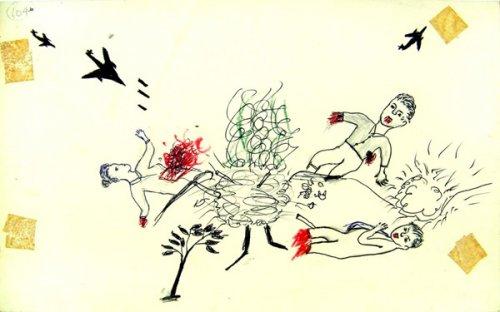

Khamvongsa showed Uy a stack of papers scrawled with simple drawings, done in pencil, crayon and marker. They looked like the work of children. Except the pictures showed people running from bombs, bleeding and digging graves. They were messages from the past with a history of their own. The drawings came from refugees in Thai camps. An American volunteer gathered them and gave them to Senator Ted Kennedy. In 1971, Kennedy held hearings on the bombings in Boston’s ancient Faniuel Hall, and included these drawings. The Departments of Defense and State had testified that the bombings were targeted and didn't hit villages.

Still, little changed. And the drawings sat gathering dust in a Washington, DC, office for years.

"Our elders are not talking about it," says Uy. "So we’re losing our history we're losing part of our identity here.”

Uy and Khamvongsa created a traveling art exhibit centered around the drawings, and amassed supporting evidence. There was much more of it available than before. In 2000, President Clinton had declassified the CIA documents that confirmed the secret bombings and discredited State and Defense Department testimony. Teams recovering unexploded bombs in Laos provided shell casings labeled “Made in the USA” and the pilots who dropped the bombs came forward. But Khamvongsa, Uy and the newly-formed Legacies of War group still faced considerable resistance.

“We got resistance from the military who didn't want to share the classified information," Uy says. "We got resistance from the local Lao community because they don't share bad stories about our community. And then we got resistance from just the general populace who was saying 'But we saved you, right? That was a good thing.'"

But Uy felt it was part of her civic duty as an American to spread word of what happened. And she says Obama was receptive to that message in part because of his own experiences.

“For me, it's very significant because it's a brown president looking into the eyes of other brown people saying, 'I acknowledge what our US government has done and I'm going to do something to change it,'" she says. "I don't think any other president would be as sensitive necessarily, just because of his lived experience being a biracial child living and growing up in a racialized United States.”

Citizens recognizing a wrong and working together to set it right — Uy says that's what makes America great.

"We have the freedom and the honor of being in a country that allows us to do that," she says. "And so that's part of us being Americans.”

Subscribe to Otherhood on iTunes, and like its page on Facebook. Tweet questions and comments to Rupa Shenoy @RupaShenoy.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?