The filibuster that tried and failed to stop the advancement of equality, 59 years ago today

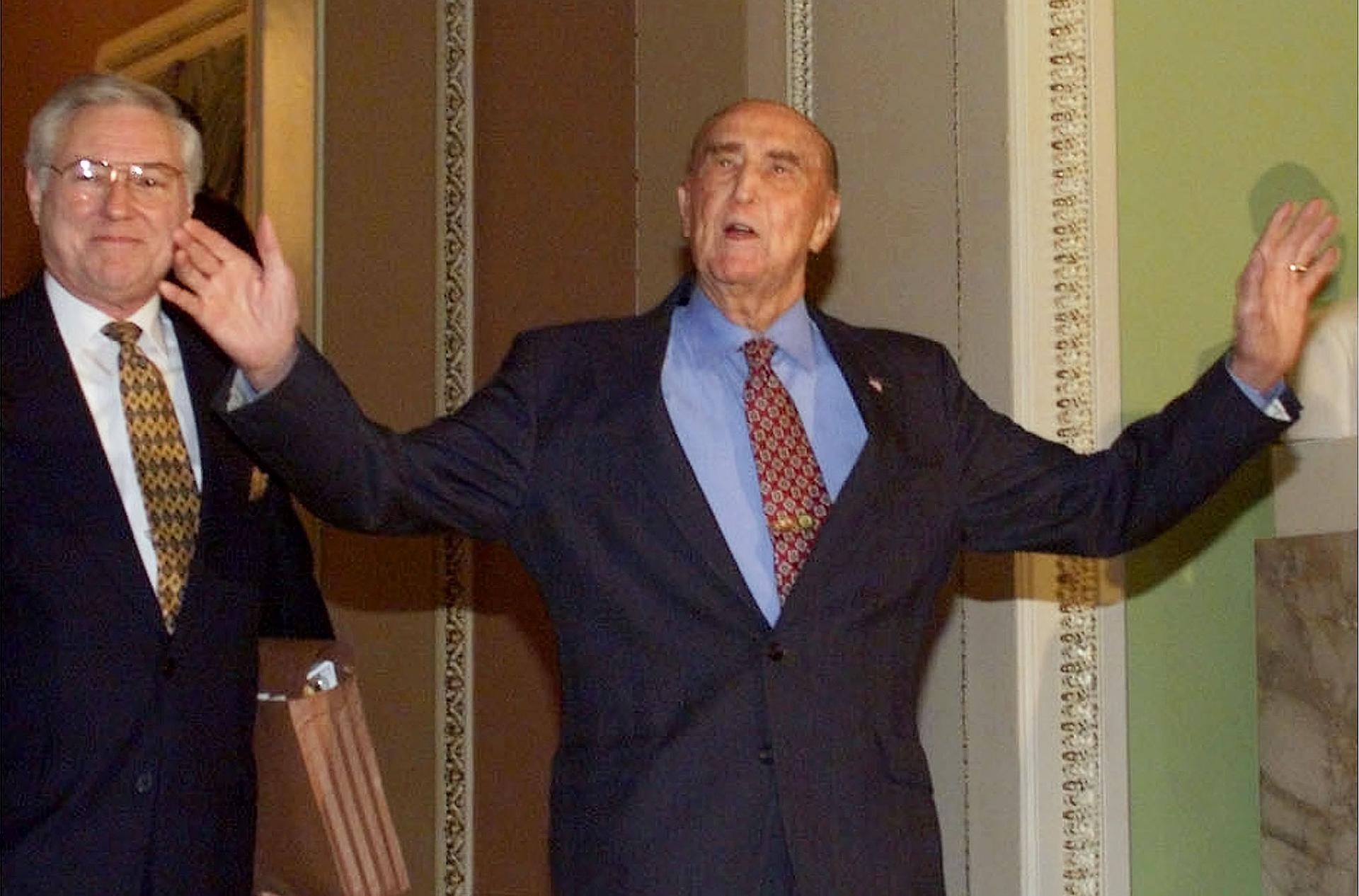

Sen. Strom Thurmond greets photographers as he arrives for the impeachment trial against President Bill Clinton January 14, 1999.

I want to take a moment and recall a moment in US Congressional history by thinking of it in a slightly unorthodox way. Filibusters come and go in Congress. Long ago they were retired in the House, but they still make news in the Senate.

When we look at famous filibusters in the US Senate, they’re often measured by the length of time lawmakers were able to continually hold the floor by speaking, even if it meant uttering nonsense for some of that time. Consider the moment when Senator Ted Cruz of Texas read the Dr. Seuss book “Green Eggs and Ham” during an Obamacare filibuster.

But I want to remember another filibuster — from 1957 — not for its length of time, but for what it represents. This filibuster was carried out for more than 24 hours to prevent the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. It was the last stand by a group of senators who used the Senate rules to maintain a state of racial injustice that befell the United States for nearly a century. It’s a lyric of intolerance — an epic poem of sorts on institutionalized racism.

There are other more familiar historic lyrics from our American nation — lyrics that deliver a different message that show how we struggle to be a more perfect union. Take this excerpt from “Leaves of Grass” by Walt Whitman:

The runaway slave came to my house and stopt outside,

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him

limpsy and weak,

And went where he sat on a log and led him in and assured

him,

And brought water and fill’d a tub for his sweated body and

bruis’d feet,

And gave him a room that enter’d from my own, and gave

him some coarse clean clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his

awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and

ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and

pass’d north,

I had him sit next me at table, my fire-lock lean’d in the

Corner.

I’m also reminded of the powerful “Let America Be America Again” poem from Langston Hughes in 1938:

O, let my land be a land where Liberty

Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath,

But opportunity is real, and life is free,

Equality is in the air we breathe.

(There’s never been equality for me,

Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”)

Say, who are you that mumbles in the dark?

And who are you that draws your veil across the stars?

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek—

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

I am the young man, full of strength and hope,

Tangled in that ancient endless chain

Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land!

Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need!

Of work the men! Of take the pay!

Of owning everything for one’s own greed!

I am the farmer, bondsman to the soil.

I am the worker sold to the machine.

I am the Negro, servant to you all.

But these lyrics, powerful as they are, speak of only a partial history. Their power is rivaled by words spoken without fear, with patriotic fervor, with a passion that makes us gasp today.

Consider the Russell Senate Office Building, named after US Senator Richard Russell of Georgia. It is the oldest Senate building. It’s a building where mostly white men spoke to history in grand lyrics of the principles they held dear. For example, Russell said this in 1935:

"As one who was born and reared in the atmosphere of the old South, with six generations of my forebears now resting beneath Southern soil, I am willing to go as far and make as great a sacrifice to preserve and insure white supremacy in the social, economic, and political life of our state as any man who lives within her borders."

Russell was willing to lay down his life for white supremacy. It feels and sounds upsetting, and so far out of the mainstream of today's politics. It was coming from a man who quite legally and proudly, and under banner headlines in the leading newspapers of the day, filibustered a civil rights bill back in 1935 — an anti-lynching bill. He spoke for six days straight to preserve the legality of hanging black people in public by their necks until they were dead — an act we would call terrorism today.

But it was called patriotism then.

I want to warn you the language of this legal American politics we like to think of in the abstract is only going to get more upsetting, and perhaps you may want to stop reading now. Though I hope you don’t.

At precisely 8:54 p.m. on August 28, 1957, Senator Thurmond began the longest continuous filibuster in US history. A final stand against a tide of history that was overwhelming the forces of racism and white supremacy that dominated the South and Southern lawmakers in Congress.

But almost a decade before Thurmond's filibuster, Southern state separatist leaders had revolted in opposition to President Harry Truman's civil rights platform in 1948. Democrats dubbed themselves “Dixiecrats” and spoke about taking back their country that was being turned into an unrecognizable dictatorship.

Then the governor of South Carolina, Strom Thurmond spoke at the Dixiecrat Convention of ‘48, like a member of the Republican faction we would call the Tea Party today.

“[The Civil Rights Act] simply means that it's another means, that it's another effort on the part of this president to dominate the country by force and to put into effect these uncalled for and the damnable proposals he has recommended under the guise of so-called ‘civil rights.’ And I tell you, the American people, from one side to the other, had better wake up and oppose such a program, and if they don't the next thing will be a totalitarian state in these United States.”

But the language you’re about to read you won't hear from the Tea Party today, even though it was legal, permissible, newsworthy, and part of the so-called racial debate back in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“There's not enough troops in the army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the n***** race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches,” Thurmond said.

My god, that is upsetting. And I grew up at a time when people around me said it all the time. From 8:54 p.m. on August 28, 1957 to 9:12 p.m. August 29, 1957 — Thurmond delivered the longest filibuster on record to defend the rights of racits. It’s the longest filibuster in American history at 24 hours, 18 minutes.

But it is no Olympic event. It is a lyric of hatred and an endorsement of violence and bigotry that stands as a national shame. Here’s a bit of what he said on the Senate floor:

"I am convinced that this is bad proposed legislation, which never should have been introduced, and which never should have been approved by the Senate. I urge every member of this body to consider this bill most carefully. I hope the Senate will see fit to kill it."

The word “kill” feels as reckless and brutal and offensive as that N word, spoken without a care in the world in this lyric of hate. It was a lament for a tradition of segregation, vigilantism, death, and hatred disguised as something called “state rights,” a principle spoken of quite vigorously today.

Governor Thurmond was the Dixiecrat’s presidential nominee in 1948. There is a monument to him in Washington and Alabama — places where you can see no monuments or commemoration of the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow or segregation.

Well, maybe the White House. It was built by slaves, after all, as First Lady Michelle Obama reminded us recently. But Thurmond lost the political battle, even if the late senator still holds the record for filibustering on this day in 1957.

This story first aired as an essay on PRI's The Takeaway, a public raio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.