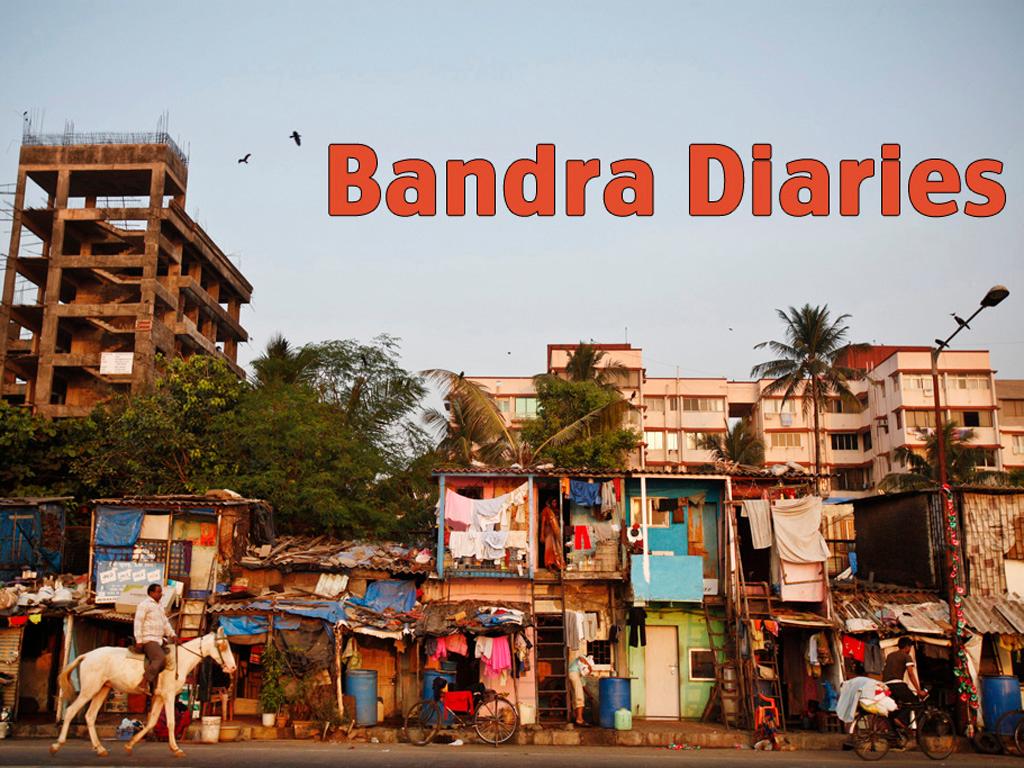

Bandra Diaries: surrogacy turned nightmare

Illustration by GlobalPost.

Editor's note: The Bandra Diaries is an occasional series that details life in today's India.

MUMBAI, India — “Chai Baby,” “Baby Masala” and “Made in India.” These are a few of the many blogs written by infertile Westerners trying to start a family through surrogacy in India. For the most part, the blogs tell tales of frustration, nervous anticipation and joy.

Commercial surrogacy has boomed in recent years as a result of India’s low cost of labor, lack of regulations and relatively inexpensive yet high quality medical care.

Surrogacy, which can cost upwards of $70,000 in the United States, is only a quarter of that in India. The Indian women who carry the babies earn about $5,000 to $7,000, upwards of 10 years’ salary for rural Indians.

“India is fast becoming a hub for surrogacy,” said Amit Karkhanis, a lawyer in Mumbai whose office, KayLegal, gets one new query a day from someone who wants to come to India to have a baby via surrogacy. “Five years ago, we were not even doing this.”

But not every surrogacy story has a happy ending, and given the fact that each country has its own laws on the matter, some Westerners who have engaged in the practice in India are finding themselves in legal limbo. As a result, the Indian government may soon regulate the surrogacy industry.

Consider the case of Kari Ann Volden, from Norway.

Volden visited the Rotunda infertility clinic in the Mumbai suburb of Bandra in early 2009. There she had an embryo — made with both a donated egg and donated sperm — implanted in the womb of an Indian mother tasked with carrying the baby to term, according to the clinic’s medical director and news reports.

Nine months after her trip to Rotunda, Volden’s surrogate gave birth to twin boys. Volden returned to Mumbai to pick up her babies and bring them home.

Norway grants citizenship to babies born abroad to either a Norwegian mother or father. However, surrogacy is illegal in Norway, like in many European countries, and the Norwegian government considers the woman who gives birth to the child — no matter whose egg was used — to be the mother, according to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration.

In this case, neither the egg nor the womb belonged to Volden. Furthermore, Volden used donated sperm and therefore cannot establish that the father is a Norwegian citizen or resident. By Norwegian law, the Indian surrogate is the mother of the twins, and they are not eligible for Norwegian citizenship.

The story gets even more complicated.

India recognizes the mother as Volden and therefore has not made the twins Indian nationals.

Norway allows adoption, but a combination of national and international regulations governing adoption makes the process difficult and uncertain.

The twins are now stateless.

Volden, who was not available for comment, is the latest in a string of Westerners with newborn babies made in India who have found themselves caught in a state of legal limbo.

To address this and prevent future legal battles, India’s health ministry is trying to pass a bill, called the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Bill – 2010, that will regulate the surrogacy industry. The bill is currently awaiting approval from the law ministry.

Some like Karkhanis have blamed the Rotunda clinic for not ensuring that Norway would have agreed to take the babies before conducting the surrogacy procedure.

Gautam Allahbadia, medical director of Rotunda, said the clinic asked Volden before they began the procedure if Norway would grant citizenship to the babies, and she said it would.

As a result of Volden’s case and other such citizenship disputes, the bill to regulate surrogacy contains a clause that outlaws embryo adoption in which neither the egg nor sperm of the intending parents is used, Allahbadia said.

The bill also stipulates that the clinic ensure that the future mother’s home country allows surrogacy and will permit the baby into the country as her biological child.

“We lived and learned,” said Allahbadia, who is on the bill’s drafting committee. He said that once the bill passes, “it completely protects both the surrogate and the intending parents from any litigation after the birth.”

The bill will also affect Indians, who have likewise begun to choose surrogacy as a way to have children. The Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre in Mumbai has seen a three-fold increase in the number of surrogacy cases in the past five years, and 80 percent of the clients are Indians, according to Firuza Parikh, director of the hospital’s department of assisted reproduction and genetics.

However, women’s rights activists have criticized the bill on the grounds that it protects the clinics and future parents but neglects the rights of the Indian surrogates, who waive their rights upon agreeing to carry the baby.

Activist Chayanika Shah argues that the bill lumps the woman and her womb together with sperm and eggs and thereby treats the surrogates like “child-bearing devices” rather than human beings.

“She is not only a womb, she is a person. She is a person who is providing labor for somebody else,” said Shah.

Shah argues there should be a separate bill that delineates the rights of a surrogate and ensures she has proper information on the risks involved.

Surrogates in India tend to be lower class women who are offering the service because they need the money to support their families. Because these women often feel a stigma around their choice to carry another woman’s child, they are unlikely to form unions or otherwise advocate for their rights, Shah said.

The surrogate, she said, “is obviously the weakest party and her rights have to be protected the most.”

The law also faces resistance from some doctors who feel it takes away their control over the process. Nayana Patel, the medical director of the Akanksha Infertility Clinic, in Gujarat, says the bill’s introduction of an agency that acts as a mediator between the surrogate, future parents and clinic could increase expenses and the chance for corruption.

An agency might be necessary in an urban setting, said Patel, whose work has been featured on the Oprah Winfrey Show. However, in a small town like hers, the clinic wants to be involved in helping choose the surrogate, ensuring she gets proper attention, nutrition and compensation, and then following up with her to help her spend her earnings as she had planned.

“In our small town it’s always better that we have direct contact,” Patel said.

Another problem with attempting to regulate assisted reproduction is that the field is rapidly evolving in India, according to Parikh. Problems arise when science and society develop faster than the law.

“By the time the bill is legislated there will be many modifications that we will have to make.”

Whether the bill passes or not, Volden is stuck in India with the twins for now. She has spent the past year living here and trying to work out a legal solution to a complex family problem.

Follow Hanna on Twitter: @Hanna_India

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!