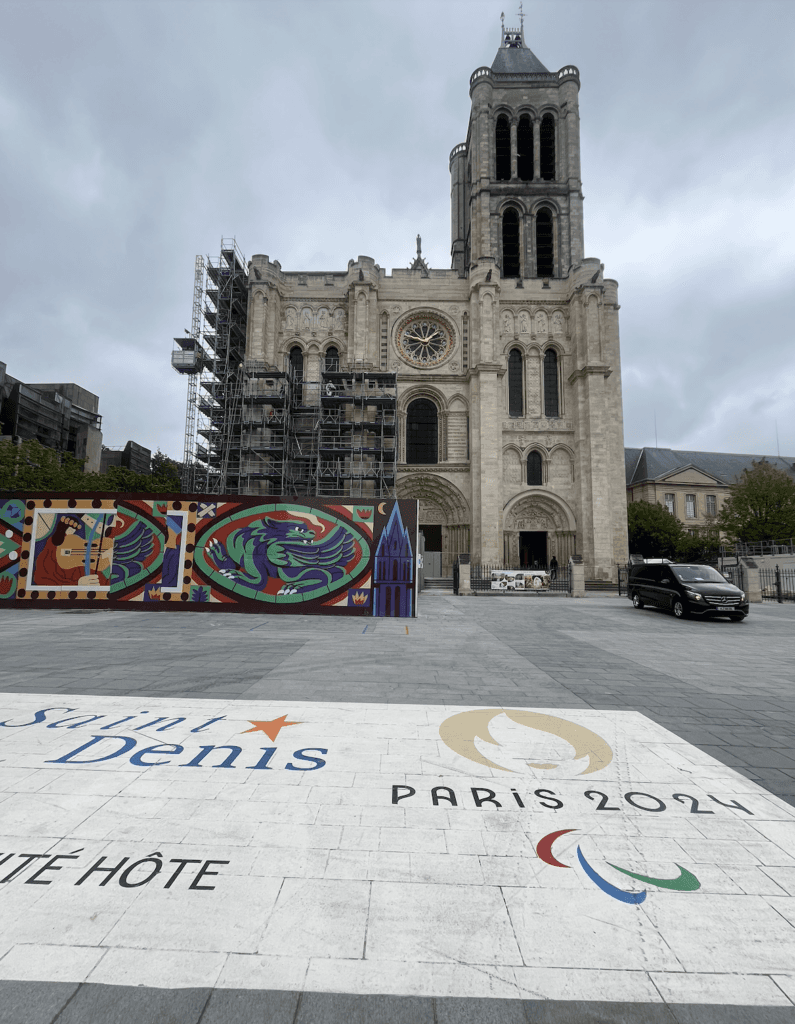

This Paris suburb gets a facelift amid controversy ahead of the 2024 Olympic Games

Rosa Poulbot, a mother of four, has lived in the Parisian suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis for 34 years. Her centuryold house stands on a narrow backstreet just a few minutes walk from the newly constructed Olympic village.

The densely populated district of Seine-Saint-Denis is where most of the Olympic Games will be hosted this summer. It’s also one of the poorest districts in Paris and has the highest number of immigrants.

Paris won the bid to host this summer’s Olympics, in part, on a promise to rejuvenate the district.

On her roof, Poulbot has erected a makeshift white sign that reads (in French): “The Olympic Games 2024. Environmental excellence means 40% more air pollution, 50% more noise for the 700 children and 2,000 residents.”

Poulbot isn’t opposed to the games but said all the construction in the lead-up to the event has been intolerable.

“I have a lot more noise, a lot more dust, a lot more fumes, from exhaust pipes. I have cracks on the walls, on the ceilings that I never had before.”

Eighty percent of investment for the Olympic Games has been focused on this sprawling district. The two main construction projects — the Olympic Village and the Aquatics Center — are both situated there.

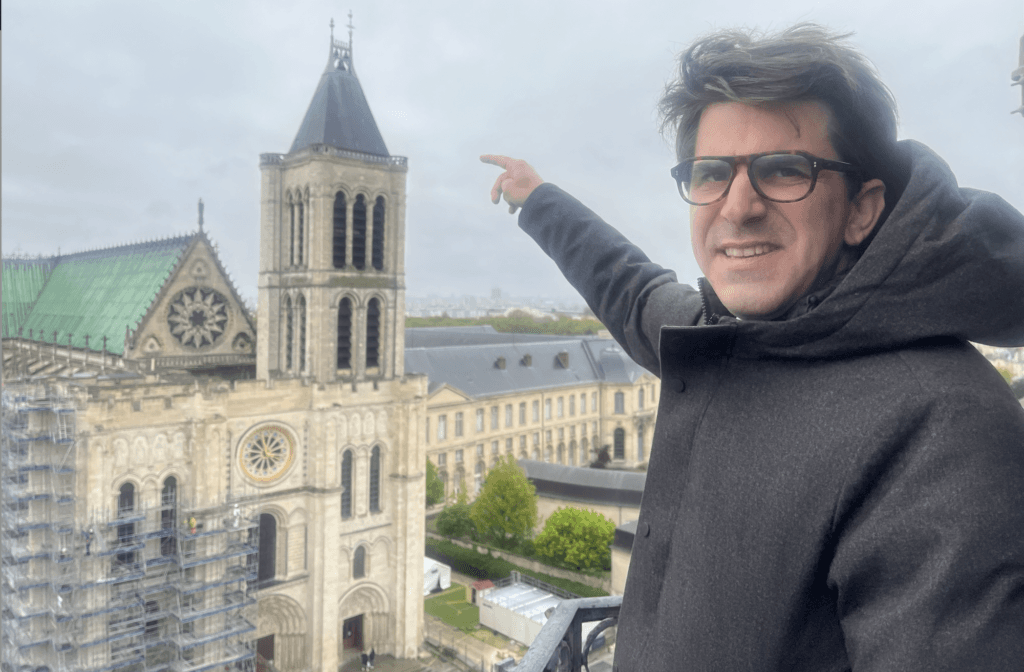

Mathieu Hanotin, mayor of Saint-Denis, has heard complaints like Poulbot’s before but he said the vast majority of local residents are excited about the Games.

“There is great pride in hosting the Olympic and Paralympic Games here and [the residents] think that the games can do a lot for the area in the future.”

Seine-Saint-Denis has long struggled to overcome its troubled reputation. The district — known in France as departments — has one of the highest levels of unemployment in France with an estimated one-third of its 1.6 million residents living below the poverty line. In 2005, riots sparked by the deaths of two teenagers fleeing police kicked off in the suburb before spreading throughout the Paris region for more than three weeks.

The district took a further battering in international media in 2022 when football fans were attacked and robbed during a chaotic UEFA Champions League final between Liverpool and Real Madrid.

Mayor Mathieu Hanotin acknowledges that the area has considerable social problems but he sees the Games as an opportunity to change the narrative. It’s a chance to show people another side of Saint-Denis and to remind everyone of the historic importance of this town, he explained.

“The roots of French history are here.”

Mathieu Hanotin, mayor of Saint-Denis

“Most of the kings of France are buried here in Saint-Denis, in the basilica. The roots of French history are here.”

Paris won the Olympic bid with a promise to deliver a cheaper, greener sporting event than previous hosts.

So far, the budget — which is fast approaching $10 billion — is still below the price tag of the Games when they were held in London, Tokyo or Rio de Janeiro. A big chunk of the money has gone toward building the Olympic Village with investment by property developers, bringing the total cost to around $2.2 billion.

Dominique Perrault, whose architecture firm led the design, said they focused on how Seine-Saint-Denis would look after the Games, not just on servicing the athletes’ needs. The village was built as a prototype for future development in the area, he said. The roughly 40 low-rise tower blocks will house about 14,500 athletes and their support teams over the course of the games. The eco-friendly village is built on a former industrial zone along the River Seine and all its energy will come from heat pumps and renewables.

But its construction has not been without controversy.

Seine-Saint-Denis has the largest number of squats and informally built slums of any department in the country, according to a 2021 report by the housing authority. It’s estimated that about 60 squats were shut down in 2023 alone.

The Seine-Saint-Denis branch of France’s interior ministry said the evictions were not related to the Games but part of normal legal procedures.

But organizations like Le Revers De Medaille (Reverse Side of the Medal), a charity that aids vulnerable people, said it finds that difficult to believe. Jhila Prentis, a spokesperson for the group and a volunteer with United Migrants said the evictions were also a symbol of how the French government views refugees and asylum-seekers.

“It’s bigger than trying to make the city look nice and shiny for the tourists.”

Jhila Prentis, spokesperson, Le Revers De Medaille

“It’s bigger than trying to make the city look nice and shiny for the tourists. I think the deeper cause is just a very hostile political attitude towards immigrants,” Prentis said.

Last year hundreds of refugees, asylum-seekers and homeless people were evicted from a squat in L’Île-Saint-Denis, near the Olympic village. More than 150 of them moved into an abandoned building in Vitry-sur-Seine in the southeast of Paris, expanding the squat’s occupants to over 450.

Prentis said 80% of them have refugee status and many have full-time jobs but finding private rental accommodations is a real struggle. Plus, racist attitudes among landlords is an ongoing issue, she said.

“The refugees say, ‘if you’re called Mohammed, don’t bother trying to find a flat.’ Many have money in their accounts and regular money coming in but they just can’t seem to get a flat. It’s really absurd,” Prentis said.

Police evictions

A few days ago, dozens of police descended on the Vichy-sur-Seine squat at 8 a.m. and evicted all the residents.

Among them were 20 children and 50 women. Prentis said the majority were from Africa, from countries like Chad, Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Some were bused to other French cities like Bordeaux and Orléans. Others were offered temporary housing in the surrounding Île-de-France region.

But Prentis said most were offered only a one-month housing contract, which means many are likely to end up back on the streets by mid-May.

French Sports Minister Amélie Oudéa-Castéra said that the eviction was not linked to the Olympics.

“These policies were implemented before the Games and they will be implemented after the Games,” she said.

Controversy around the construction of the Olympic Village doesn’t just revolve around evictions.

The 2,800 new units that will house the athletes are set to be converted into permanent homes for up to 6,000 people by the end of 2025. More than 50% of inhabitants in Saint-Denis live in social housing but only around a quarter of the new Olympic Village apartments are expected to be available for this type of accommodation.

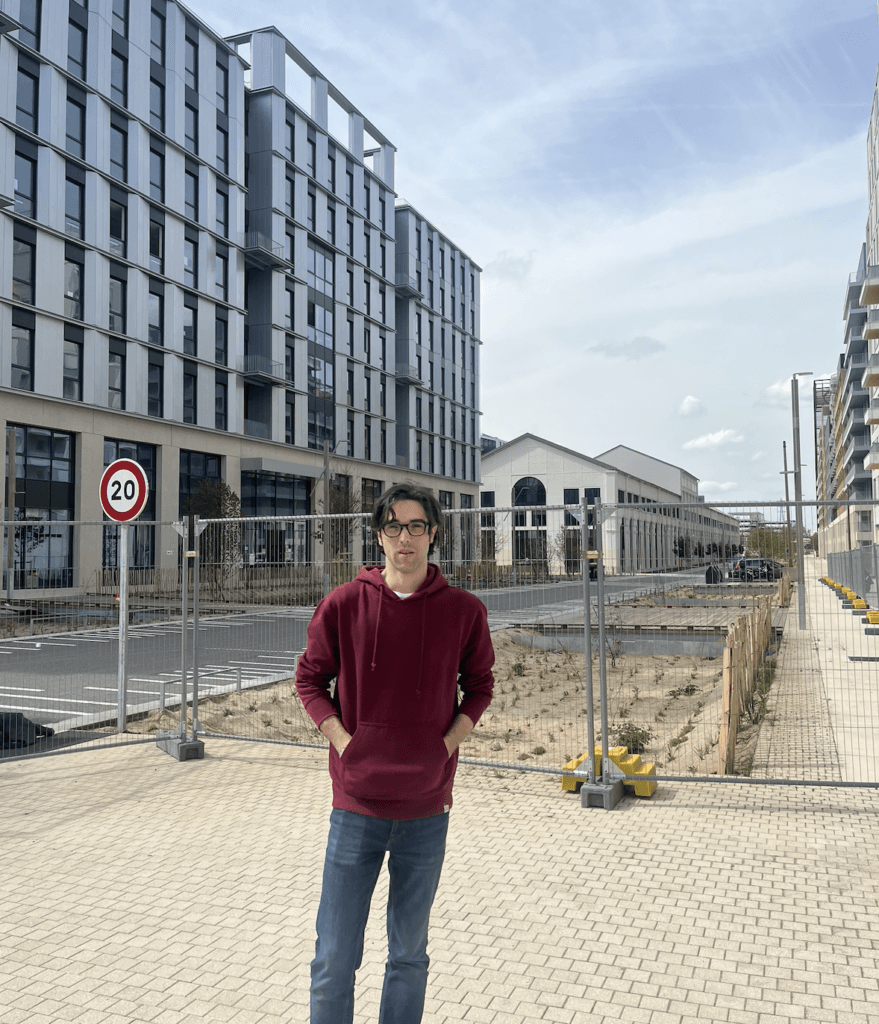

Local history teacher Alexandre Schon said the vast majority of people living in the area will not be able to afford to buy any of the new flats. Schon, who is a member of a group called Olympics 2024 Vigilance, said he worries about the potential gentrification of Saint-Denis. He bought an apartment in the area three years ago, but said today he could no longer afford it.

“This is my area. It’s my city. But the price of the apartment now would be too expensive for me.”

Saint-Denis Mayor Mathieu Hanotin said the Olympic Games cannot be blamed for the price rises. There’s a housing crisis across France, he said, and the Olympic Village was never built as a “social housing village.”

Saint-Denis already has 52% of its inhabitants living in social housing, so the challenge is to build a balanced neighborhood model that would reflect how the town could look in the future, he said.

A massive soon-to-delivered extension of the metro system into Seine-Saint-Denis will also make the area more attractive for developers and would-be home buyers. Earlier this year, Elon Musk said Tesla was moving its headquarters to the district.

Hanotin said many more people will soon be traveling to Saint-Denis for work.

“Our challenge is to encourage them to stay and live here,” he said. “We want to create a place with a lot of solidarity. But for that to work, there must be people who earn money living alongside people who earn a little less. Otherwise, it’s not solidarity, it’s social separatism.”

History teacher Schon plans to leave Saint-Denis while the Games are underway to avoid the influx of visitors, the large police presence and the restrictions in the area.

“It’s not my Olympic Games, it’s the Olympic Games for the rich, for the powerful. It’s not the Olympic Games for all,” he said.

But Mayor Mathieu Hanotin disagrees.

“The Games are for everyone,” he responded. “And I hope when visitors come to watch events in the Aquatics Center or the Stade de France that they also take the time to look around our town and visit our famous basilica. They will see that Seine-Saint-Denis has so much more to offer than what you read in the news.”

Léontine Gallois contributed to this report.