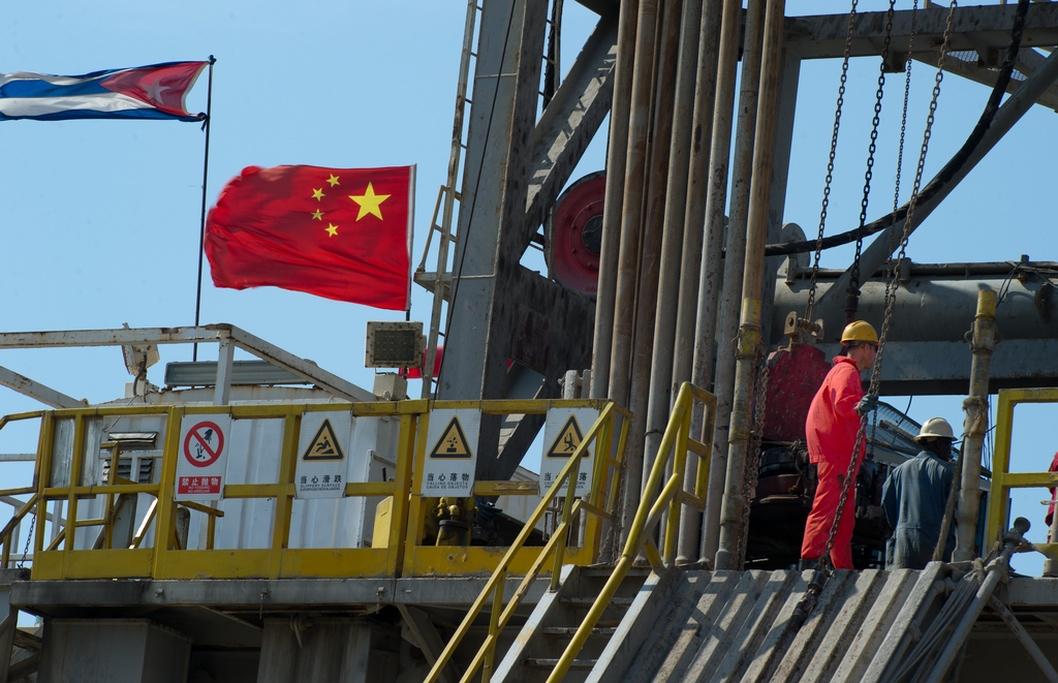

Oil discovery in Cuba gets US notice

Hunting for Cuban oil.

HAVANA, Cuba — Somewhere between here and China, a hulking, hungry oil rig dubbed “Scarabeo 9” is making its way across the oceans, preparing to put a very controversial hole deep in the Gulf of Mexico.

To nervous Floridians, even its name suggests “scare,” or “scar.” It will puncture the sea floor in Cuban-controlled waters just 60 miles off the Florida Keys, not far from a protected coastline where offshore drilling is banned under U.S. law.

More from Cuba: Economic inequality on the rise

U.S. geologists believe there may be 5 billion barrels of oil down there. Cuban studies estimate the total at four times that, enough to put the island on par with mid-size energy exporters in the region like Ecuador and Colombia.

A major oil strike could rescue Cuba’s struggling socialist system from its financial woes, giving the Castro government access to new credit and a potentially lucrative industry.

More from Cuba: Venezuelan subsidies keep Cuba afloat

Having conducted test wells in the area before, Spanish energy company Repsol and its partners are now bringing the Chinese-built Scarabeo 9 to a site off Cuba’s northwest coast, where it aims to drill as soon as November at a depth of more than 5,500 feet, deeper than the blown-out well that spewed 5 million barrels of crude into the Gulf last summer.

That disaster has added to anxiety about Cuba’s exploration efforts, but it has also intensified calls for U.S. officials to engage the Castro government on spill prevention and contingency plans.

A high-level delegation of U.S. oil-spill experts traveled to Havana this week to meet with Cuban officials. It has urged the Obama administration to cooperate with the Castro government on a joint-response plan that could avert environmental catastrophe for both countries.

The delegation included William Reilly, co-chair of the presidential commission that investigated last year’s spill at the Deepwater Horizon rig, at the well known as Macondo.

“The fact that Cuba is about to drill six wells in the next two years, some of them very deep, deeper than Macondo, in places we wouldn’t allow it if it were in our waters … you better believe that the United States has an important interest in that,” Reilly said.

“The Cubans have never regulated this industry, they don’t have familiarity with it, but they are doing things to get ready for it,” he added. “We want to make sure the Cubans have got the lessons we learned, and get a sense of what they do need — that the U.S., in its own interest — would help them get.”

Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-Fla.), a long-time Castro foe, criticized the delegation’s visit, saying it gave “credibility” to Cuba’s attempt to become “the oil tycoons of the Caribbean.” Other lawmakers have also urged retaliatory measures against Repsol.

But experts say with Cuba moving forward, the U.S. should help them do so as safely as possible. Some of the industry’s leading safety-equipment providers and cleanup contractors are nearby along the Gulf Coast, but the U.S. trade embargo bars them from doing business with the island.

In recent months, Cuban authorities have given minimal information about their drilling plans, but the U.S. delegation gave new details into the project.

The fact that the drilling rig was built in China should not raise concerns, said delegation member Lee Hunt, president of the Houston-based International Association of Drilling Contractors, a trade group. As many six other rigs already working safely in the Gulf of Mexico were built in the same Chinese shipyard, Hunt said.

“It has the latest generation of equipment,” said Hunt.

American trade sanctions against Cuba prohibited the use of more than 10 percent U.S. technology in the rig’s construction, but Hunt said the Norwegian-designed platform will have an American-made blowout-prevention system that is more advanced than the one which failed on the Deepwater Horizon.

While Cuban oil officials will manage and regulate the operations, the engineers and crews doing the actually drilling will be composed of experienced international oil workers, said Hunt. An Italian firm, Saipem, will be operating the rig, and Repsol’s partners include Statoil, a Norwegian company that he and others praise as a world leader in safe deepwater drilling.

When asked how closely U.S. oil companies were following Cuba’s drilling plans — and if they might be angling behind the scenes for access to its waters — members of the delegation said it would depend on the size of the find.

If the deposits hold close to 20 billion barrels, as Cuban geologists claim, that would probably attract some interest, said delegation member Richard Sears, a former vice president and deepwater drilling specialist at Royal Dutch Shell.

For now, though, Sears said, U.S. firms will likely prefer to work in parts of the world with proven hydrocarbon reserves and fewer political hurdles than Cuba. “The challenge for any company is how you allocate resources,” he said.

“Do I want to fight political and public-relations battles?” said Sears. “Or do I put my resources into other parts of the Gulf of Mexico where I have well-established leases?”