The curious case of the death of Malawi’s president

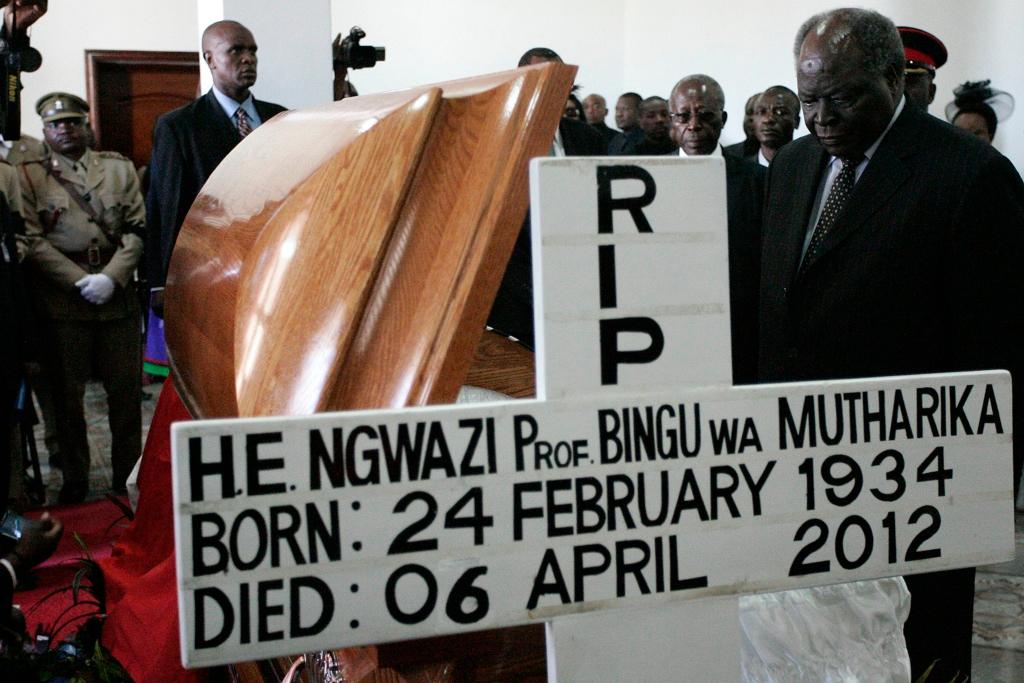

Mourners at the funeral of Malawi’s late president Bingu wa Mutharika on April 23, 2012.

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — The day began as usual, with the presidential food tester ensuring that his breakfast was free of poison.

It ended with the president’s corpse on a gurney, battered by futile resuscitation attempts, a diaper tied to his lifeless face to stanch the blood flowing from his nose and mouth as his supporters tried to convince a nation that he was still alive.

These bizarre details were part of the evidence that led to the arrests of 11 powerful politicians and former officials in Malawi last week, accused of attempting a coup by pretending President Bingu wa Mutharika had survived a heart attack last April.

With his food tester and his dislike of dissent, Mutharika had all the hallmarks of an authoritarian ruler. For nearly two days after his death, his cronies kept up the ruse that he was still alive, stalling for time in an attempt to maneuver his brother into the presidency, according to allegations contained in a 94-page report produced by a Malawian government inquiry.

Among the 11 people charged with treason, now out on bail, are the country’s former economic planning minister and the late president’s brother and heir apparent, Peter Mutharika, a graduate of Yale Law School.

Under Malawi’s constitution, Joyce Banda, the then-vice president, was to take over as president, but she had fallen out with Mutharika. His supporters were determined to keep her out of power.

Bingu wa Mutharika’s body, beginning to decompose but still with a tube in his mouth, was even flown to South Africa under the pretense of being ill and needing medical treatment. His personal doctor “opted not to disconnect all the medical equipment to the late President’s body in order to give an impression that the President was still alive,” the report said.

The exhaustively detailed report tells of the confusion in the hours after Mutharika collapsed during a morning meeting. He died in an ambulance on the way to hospital, with the inquest putting the time of death at 11:25 a.m.

But despite it being clear that Mutharika had died, medical attempts to “save his life” continued throughout the day, with false statements given to the press about the president’s condition.

An air ambulance that arrived from South Africa refused to depart with the Malawian president because the pilots didn’t have clearance to transport a dead body. After receiving approval, the pilots refused to take off because their flying hours for that day had expired. The South African high commissioner and Zimbabwe’s ambassador to Malawi were summoned to the airport to intervene.

Hours later the air ambulance landed at Waterkloof airforce base in Pretoria. Mutharika’s body was transported to the emergency ward of One Military Hospital, where it remained for about 15 minutes, before being taken to the morgue.

Back in Malawi, cabinet ministers were trying to get an injunction to stop the swearing in of Joyce Banda. Six ministers held a late-night news conference a day after Mutharika's death to insist he was still alive.

According to the inquiry report, Peter Mutharika suggested to army commander Gen. Henry Odillo that the military “just take over.” Odillo refused, saying the constitution should be respected.

In the end, a fed-up South African government said that, “if the Government of Malawi was not going to announce the death of President Mutharika, then President Jacob Zuma of South Africa was going to do it.” Malawians were finally told of the death of their president nearly 48 hours after he had passed. Shortly after, Banda was sworn in as president.

Despite the disturbing revelations in the report, the arrest of the “coup plotters” has sent shock waves through Malawi, sparking accusations that Banda is cracking down on her opponents ahead of elections next year. While she has been feted by the international community for her relatively progressive stances on issues such as homosexuality and human rights, she is facing growing discontent at home over rising inflation and the devaluation of the Malawian currency.

A spokesman for Banda denied the arrests were politically motivated. But they sparked violent protests in the country’s commercial capital, Blantyre, where supporters of the late Mutharika’s Democratic Progressive Party threw stones at police officers, who in turn used tear gas to try and disperse the crowd of about 500 people.

Edge Kanyongolo, a legal expert and professor at the University of Malawi, said that while the commission of inquiry’s report was largely thorough and comprehensive, “some think the inquiry itself was politically motivated, a setting of the stage for what would come next.”

“It seems like there were clear violations of the law,” Kanyongolo said. “From a legal side, it is a case that has a clear basis. But politically, it draws questions about timing.”

After returning from South Africa, Mutharika’s body lay in state with heavy makeup to conceal the damage from resuscitation attempts and decomposition. The date of death on a cross accompanying the body was changed several times during the course of the public viewing, from April 7 to 5th to 6th, the inquiry's report said.

In the end, the commission of inquiry found that “the handling of the body of President Bingu wa Mutharika, due to attempts to conceal his death, to have been most unbefitting for the honor and respect of a Head of State in death.”