These photos will help you appreciate the beauty and diversity of birds

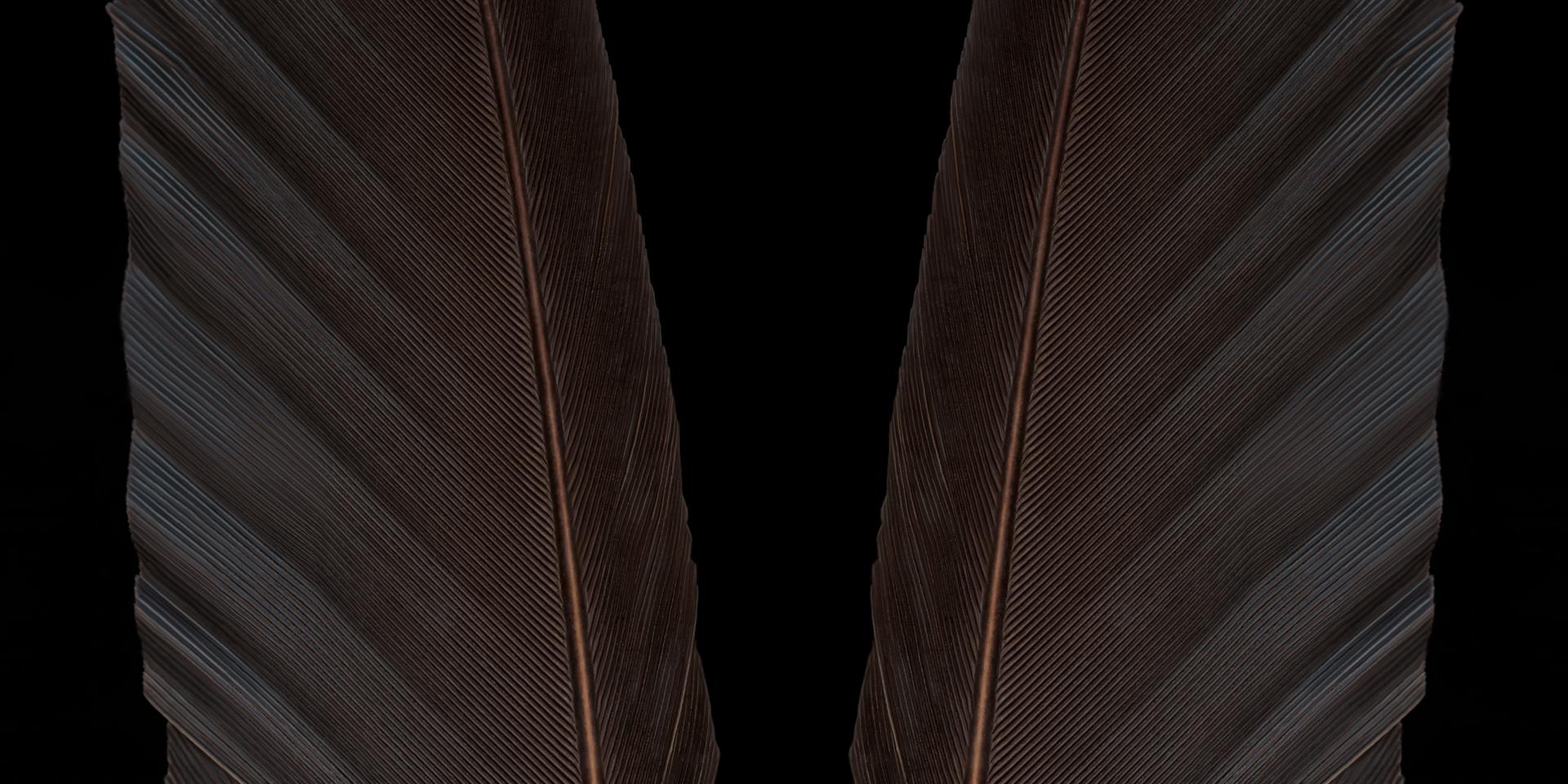

This photo of a bald eagle’s wing feathers is one of photographer Deborah Samuel’s favorites from her new book. From "The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds."

Photographer Deborah Samuel began her latest project after experiencing a series of profound losses, of family and other loved ones.

“It seems that as soon as one left, the next one came up, and it was even worse,” she says. One afternoon, sitting in her backyard and watching the birds fly, she was overcome by their elegance and freedom. That’s when she knew: “I had to find that beauty again.”

Her search culminated in a new book called The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds, which features 135 images of specimens found in the ornithology collection at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Canada.

The museum contains thousands of skins, nests, eggs and blood and tissue samples, organized neatly and tucked away from damaging light, heat, and humidity. While scientists primarily use the ornithology collection, mining samples of skin and tissue for molecular research, the ROM often works with artists, too.

Samuel’s photographs offer an intimate tour of the collection, with images ranging from close shots of the details of a single feather, to a full study of the tangled and twisted fibers of a nest. Bright and colorful plumage stands out in stark relief against a black background, while dark feathers almost vanish, and speckled white and blue eggs practically glow.

“We think it’s great that we’ve got this cross pollination between science and art. The collections are one of those things that are often hidden away in the back rooms,” says Mark Peck, the manager of the ornithology collection. “To illustrate those can only be positive, both for younger people and older people, who can see the collection not just as a bunch of dead stuffed birds.”

Though Samuel does not have a scientific background, she has worked with animals through her photography for the past 16 years.

“I’ve always been interested in the science behind life,” she said. “My interest has always been what makes an animal tick — mentally, emotionally, physically.”

Before birds, Samuel created a photo series of animal skeletons called Elegy. For part of that project, she used skeletons from the ROM collections.

“Then they said to me, what are you working on next?” Samuel remembers.

For her new book, Samuel focused on finding what she considered the most important aspects of each individual bird. For some it may be strength, for others patterns, or just pure beauty, she says.

According to Peck, Samuel’s photographs reveal an entirely new dimension of the museum’s ornithology collection.

“Deborah’s work has brought back a certain life to the specimens,” he says. “It has given the specimens even greater value and, I believe, will inspire people to see the extraordinary beauty of the natural world.”

Both Samuel and Peck cited the photograph of the black sicklebill, a bird of paradise found in New Guinea, as one of their favorites. During courtship, males extend their black breast feathers to reveal iridescent blue tips.

“It’s so poetic, the way the feathers move,” said Samuel. “There’s a poetry in all of this.”

This story was first published by Science Friday with Ira Flatow.