The workers who pick your summer berries are asking you not to buy them

Ramon Torres, president of Familias Unidas por la Justicia, rallied workers and supporters outside the gates of Sakuma Bros. berry farm in Washington state on Monday, July 18, 2016.

Go into any grocery store this time of year and you’re sure to find an abundance of neatly packed cartons of blackberries, blueberries and strawberries. For many it’s a hallmark of summer.

Beneath the sweetness of these berries, though, lies a bitter labor dispute that has been roiling for years at Driscoll’s, the world’s largest distributor of berries — the ones you find at Costco, Target, Whole Foods and host of other grocery stories.

The conflict came to a head last week in Washington state, when farmworkers and their families marched alongside hundreds of supporters on a usually sleepy country road about an hour north of Seattle. With bullhorns, musical instruments, honking cars and chanting — “Wage theft is not OK, Sakuma has to pay” — the loud procession made its way to the family-owned Sakuma Brothers berry farm and packaging plant.

The workers, many of whom are undocumented indigenous Mixteco or Triqui from the Mexican state of Oaxaca, were marching to commemorate the third anniversary of their dispute. Organized by the independent Familias Unidas por la Justicia (Families United for Justice), protesters rallied for a continued consumer boycott of Driscoll’s berries and to put pressure on Sakuma Brothers to sign a contract allowing union representation for seasonal farmworkers.

“Farmworkers are the people who are most oppressed in the social and labor ladder,” the group’s president, Ramon Torres, wrote in an email, translated from Spanish. He and a growing number of farm worker unions across the nation are hoping to change the way workers are treated.

Also: Workers may unionize — but not farmworkers. A lawsuit in New York seeks to change that.

In a statement on their website, the union alleges that Sakuma Brothers is guilty of “systematic wage theft, poverty wages, hostile working conditions, and unattainable production standards.” They’ve organized protests, strikes, legal actions and boycotts of both Sakuma Brothers and Driscoll’s, their largest client for fresh berries.

For their part, Sakuma Brothers feel unfairly targeted. The Sakuma family has a 100-year history as berry farmers in the region. They own and operate a 1,000-acre Washington farm and processing plant in Burlington, Washington, that employs hundreds of seasonal laborers each year. Though the current president and CEO, Danny Weeden, was hired from outside, the Sakuma family remains deeply engaged and invested in the company.

In an email to PRI, former CEO Steve Sakuma says that worker welfare is of utmost importance and argues that many of their workers see them as charitable employers.

“The Sakuma generations grew up understanding that our farm workers are the backbone of our success and it is our responsibility to care for them as we would want to be treated; with respect. We feel that our philosophies are working. We have many families who return to work for us year after year,” writes Sakuma.

But University of Washington student Elizabeth Alvarado says the fact that many families return each year isn’t necessarily evidence of a happy workforce. A third generation Sakuma Brothers employee, Alvarado started working at the farm at age 12.

In a recent article for the Seattle Globalist she wrote: “No one does it because they love the job. Workers return year after year because they need the money and they don’t have many other opportunities. At least, that’s how it was for my grandparents.”

At the peak of the 2013 summer harvest, seasonal workers not participating in the H2-A guest worker program began organizing protests and work stoppages, and demanding equal treatment. In response to the unrest, Sakuma Brothers suspended its use of the H2-A program after just one year, but workers’ demands for better treatment have continued.

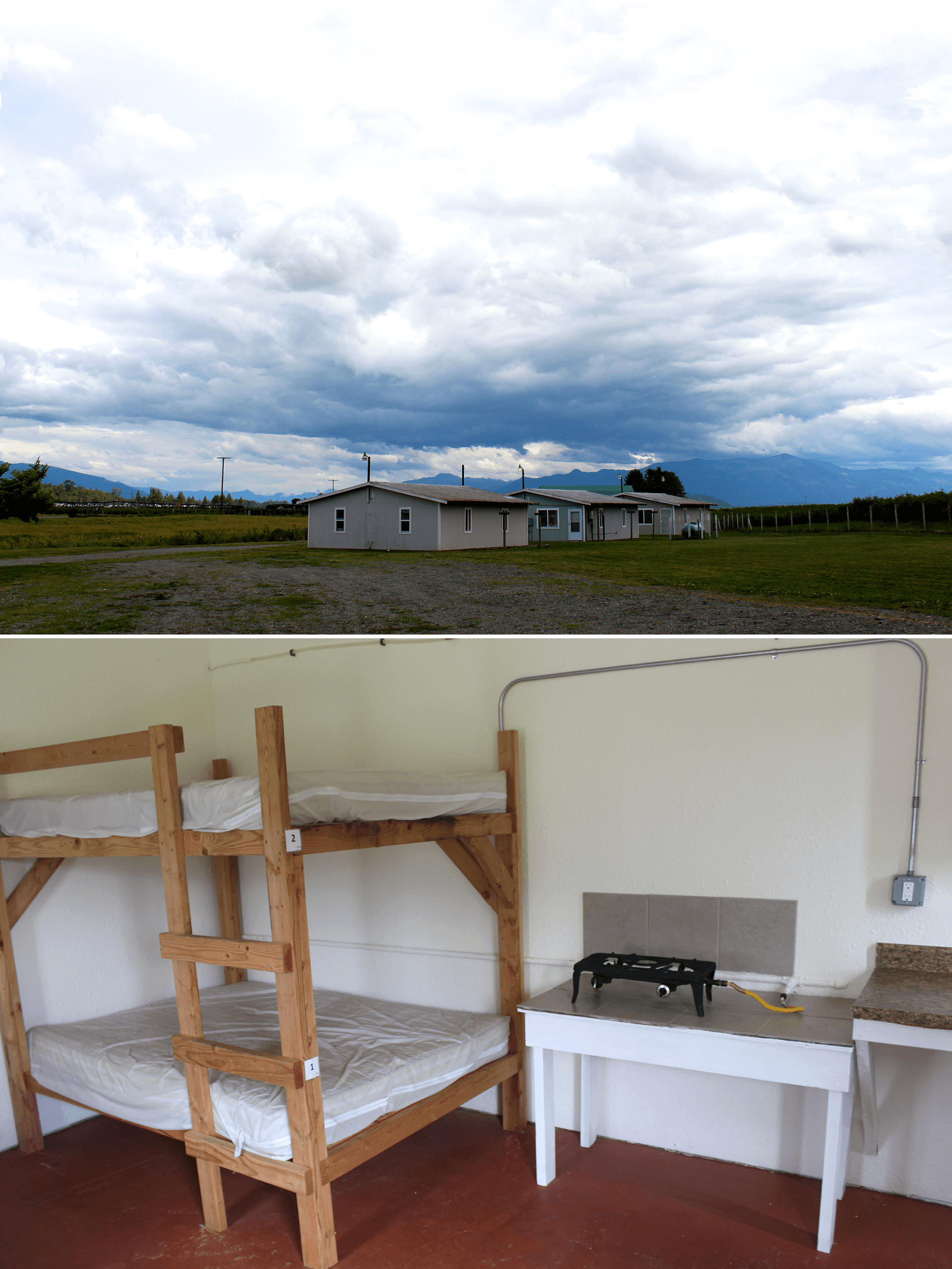

In 2015, the Washington Supreme Court ruled in a lawsuit that workers at Sakuma and across the state are entitled to paid rest breaks. Beyond that, the workers’ group says that they have seen some improvements to housing conditions and wages have been increased. Still, the they say, it’s not enough.

Another worker, Alicia Hérnandez, 18, of Oaxaca says she recently worked a 10-hour day and came away with $40 in pay. The blueberries she harvested during that time will go for as much as $4 per pint in grocery stores.

Sakuma Brothers says that in June they paid both Telles and Hérnandez what amounted to between $12.92 and $18.84 per hour for the strawberries and blueberries they picked. They say they would never pay less than minimum wage. FUJ says this sort of discrepancy in pay is the reason they want to move beyond the piece rate wage and instead institute a flat $15 per hour pay rate. (Workers are, for the most part, paid largely by how much produce they pick rather than by the hour.)

The stories of disadvantaged workers are familiar to the Sakuma family. Like other Japanese Americans in the US in the first half of the 20th century, the Sakumas worked as underprivileged laborers, facing racist and exclusionary laws.

Also: A lesson from history about protecting migrant workers

“When my father started the farm in Burlington, says Steve Sakuma, “they started with no land and minimal assets to farm. They rented land and turned an abandoned chicken coop on the rented farm into their home shelter. They later were able to purchase some property which they farmed and built a house in which to live.”

But World War II threatened to change all of that. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, the family was forced to give up their farm and was forcibly relocated to concentration camps. Despite this loss and shame, the family maintained a fierce allegiance to the American dream. Their patriotism was noted even among their peers, earning coverage in a camp newspaper as “the largest nisei service family in the US Army,” with six sons reporting for active duty.

After the war, the Skagit Valley property the family had worked hard to acquire was, remarkably, returned to them by a neighbor who had cared for it in their absence. The ability to overcome racism, poverty and illegal imprisonment has now been woven into the family’s success story.

“Our parents’ generation truly lived the American Dream; start with nothing but the opportunity to work hard and build a legacy around the Sakuma family name…. Our parents worked their way through poverty and expected no special treatment,” writes Sakuma.

The irony is not lost on the workers’ organizers.

“We believe Sakuma is replicating the oppression they suffered in the past … we can’t believe that after going through that, they are treating us this way,”says Torres.

Still, three years later, there could yet be an amicable resolution. On Friday, Sakuma Brothers met with representatives from the workers’ group to begin negotiations for a union contract. While the United Farm Workers of America has union contracts across the country, the protesters’ group would be one of just a few regional organizations representing farm workers.

“We do believe in the freedom of association,” says CEO Danny Weeden. He wants the workers’ union to sign a memorandum of understanding that would legally bind the workers to the same standards established in the National Labor Relations Act, which regulates the activities of other labor unions but doesn’t extend to farmworkers. The agreement would mean the workers’ group couldn’t call for boycotts of Sakuma clients like the one they’ve organized against Driscoll’s.

Kevin Murphy, Global CEO of Driscoll’s, says that their company has been working with Sakuma Brothers on improving conditions for farmworkers since 2013. “They’ve done a lot of work in the years to make the adjustments necessary,” he says.

Still, Murphy supports the workers’ right to unionize, protest and even boycott. He trusts Sakuma Brothers will take the necessary steps to resolve the labor dispute.

“We don’t like that we’re getting boycotted, but that’s not the point,” he says. “We want them to resolve the issue.”

In the lead-up to last week’s meeting, the mood among members was hopeful but skeptical. They were pleased to see their efforts pressured Sakuma into considering the union contract, but concerned about the terms of Sakuma’s memorandum and a breach of confidentiality they say was agreed upon prior to the meeting.

“While we certainly were encouraged by Sakuma approaching us initially, unfortunately, the recent press statements and actions by Sakuma, are far from encouraging,” says a statement from the group.

Still, this is the closest the two groups have come to resolving this conflict since it began three years ago. As the negotiation process unfolds, Torres encourages consumers to continue to support a boycott of Driscoll’s berries. Torres reported via email that Friday’s meeting was “productive” and that they are “looking forward to continuing the dialogue.” For now though, he’s still looking for consumer action.

“We ask the public to grow their own berries and support the boycott against Driscoll’s,” says Torres.

The Sakuma family, on the other hand, is feeling pressure from clients and customers to resolve this dispute as soon as possible.

While other allegations of labor abuse at Driscoll’s affiliates continue to mar the company’s reputation, consumers may soon be able to eat Sakuma berries with a bit more ease about the circumstances in which they were harvested.

This story was updated on July 19 to include new information provided by the Sakuma Brothers and more discussion of how workers are paid. On July 20, we added additional comment from the distributor, Driscoll’s. An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the Familias Unidas por la Justicia as a non-profit organization. It is, in fact, an independent union recognized by the state of Washington.

More: How the produce aisle looks to a migrant farmworker