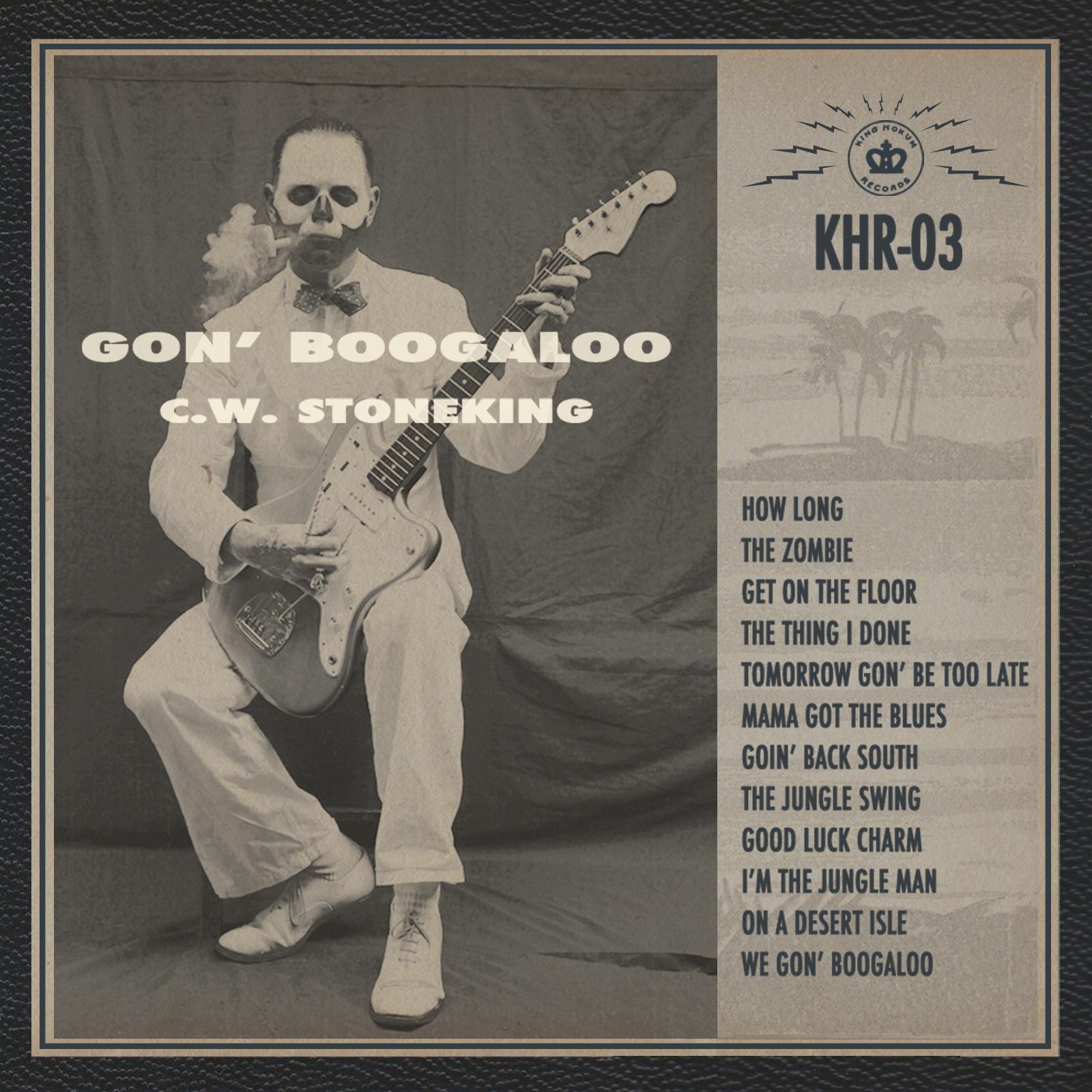

C.W. Stoneking playing his electric guitar

C.W. Stoneking is an Australian who loves the blues.

He doesn't just love it; he has made it his life. He has modeled himself on the likes of Robert Johnson and Son House.

Blues music originated with African Americans in the American South, but it’s certainly grown and changed in ways its original performers would scarcely recognize. And that can lead to conflict, especially when whites, Stoneking, perform the blues.

Stoneking says he draws inspiration from the blues music that was played in places like Mississippi in the 1920s.

He admits that the cracked deserts of Australia could hardly be more different than the lush deltas of Mississippi. But for Stoneking, the music still seemed to fit his environment.

"The first time I traveled through Mississippi, I was surprised. It was really at odds with the imaginative world that I had set these sounds into. There is a sort of ancient eroded quality to Australia, not like Mississippi's kind of green, cleared jungle and floodplains. But growing up in the desert in Central Australia, I found [the blues] fit really well with the sort of imagery and context I had put it in"

While blues music might fit the arid Australian landscape, some readers will undoubtedly cringe at the cover image of Stoneking's most recent album cover for "Gon' Boogaloo."

In the US, the recent history of minstrelsy and black-face performances (specifically white musicians performing in stereotyped African American vernacular) is hard to escape.

Upon closer inspection, it's clear that his face is painted as a skull, the black paint serving to imply the absense of a face, rather than skin color. However, there are other questions.

Stoneking's record label, King Hokum, refers to a sub-genre of the blues, hokum blues. Hokum was known for comical and often bawdy lyrics that made frequent use of inuendo.

The genre is pure entertainment, composed for the vaudeville shows and rundown theaters home to minstrel shows in the 1920s and '30s.

Both black and white musicians sang hokum. It wasn't only white people making fun of black people, nor was it black people playing up stereotypes for a white audience. Stoneking, for his part, sings his hokum songs with a strong American southern accent, an accent specifically associated with African American residents of turn-of-the-century Mississippi.

It is doubtless that Stoneking is sincere in his appreciation of this music. Yet, there are still obvious markers of the minstrel roots of his music. References to "the jungle" and fictionalized voodoo practices abound in his lyrics.

Still, no question that I love this album. It is incredibly well-crafted and true to both musical style and recording techniques of prewar blues in the South.

Music doesn't have to be politically correct, but it should be sensitive to the music's history as well. Imitation may be a form of flattery but the history of white people's enjoyment and imitation of African-American culture has been rife with exploitation of black performers. But Stoneking makes no mention of that history — despite using a heavily affected black, southern accent.

Refusing to acknowledge this history does not impact the quality of Stoneking's album. However, it does impact my listening. Blues is black music. Blues music touches me because it is full of life. Without that context, though, it's just another piece of entertainment. And there's plenty of that out there.

Here is Stoneking in his own words, on the topic:

"I don't even think about that when I'm making the song. It's not part of my creative process to sift through the multitudes of politics and just people being bad. I try to not to act bad in everything I do and make other people feel like sh*t. Pretty much everything in life is loaded with past wrongs and unfairness and crap. You do the best you can do as a human being and as an artist and that's about all you can do no matter if you're doing blues or whatever it is. That's all I have to say about that."