He calls Yiddish a language of life — so translating Oscar-winner ‘Son of Saul’ was an especially dark experience

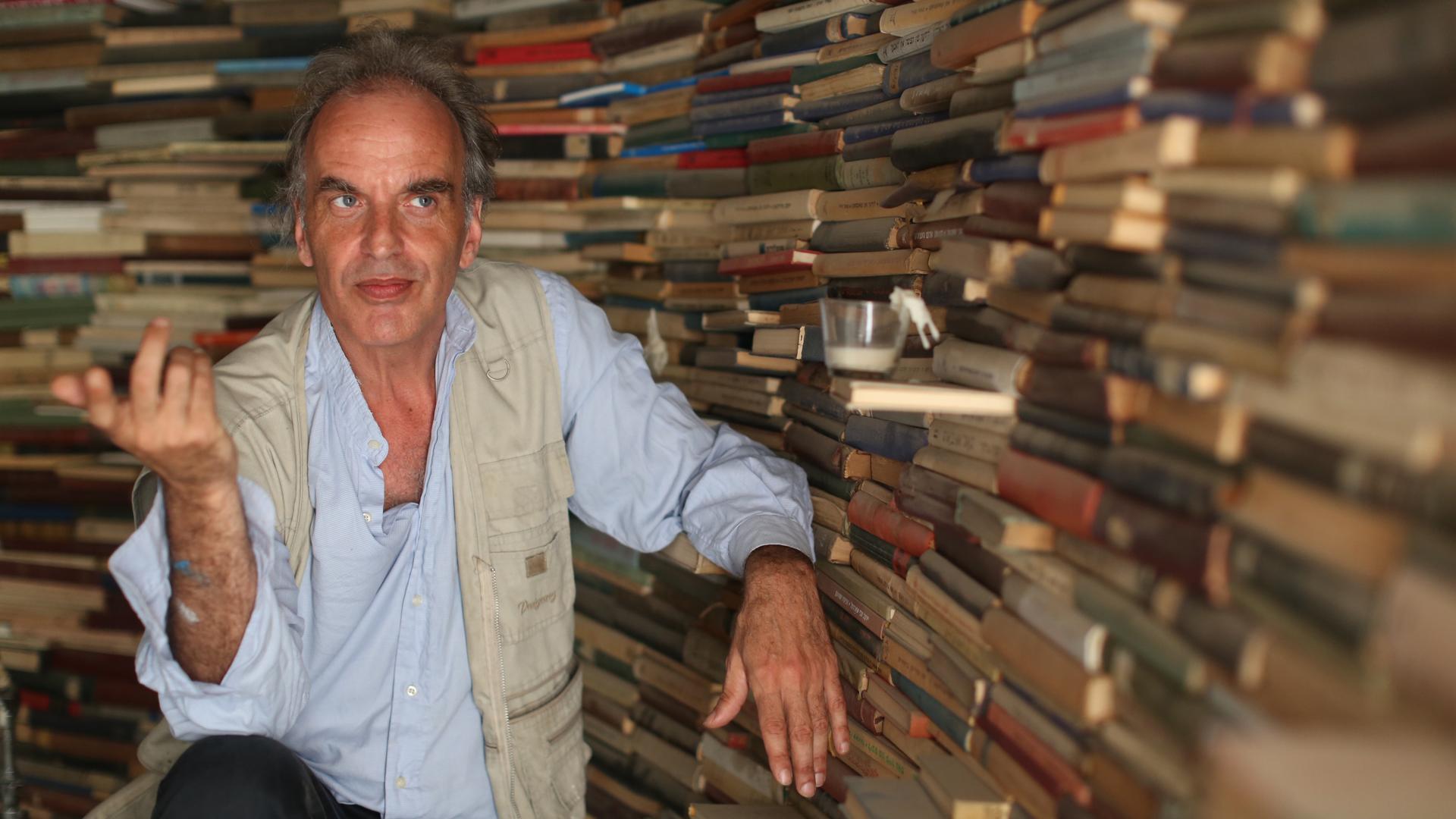

Mendy Cahan in his library, Yung YiDish, at Tel Aviv's Central Bus Station.

This year’s Oscar for best foreign language film went to "Son of Saul," a Hungarian movie about the Sonderkommando, the special squad of Jews who escorted Holocaust victims to the gas chambers in concentration camps, and burned their bodies after they were murdered.

Director Laszlo Nemes took care to include voices speaking the languages that would have been spoken during World War II, including Yiddish, the lingua franca of European Jews. Very few people speak it now, other than Orthodox families.

Nemes found a Yiddish speaker in Tel Aviv to translate the dialogue and train the actors who would be re-enacting the Auschwitz death camp scenes. Ironically, that man spends most of his days preserving everything about Yiddish that isn’t about the Holocaust.

Mendy Cahan presides over a library of 57,000 Yiddish books in an unusual setting: the fifth floor of Tel Aviv’s grimy Central Bus Station.

“You have the buses shaking and the walls vibrating here, which reminds you every time that culture is not a secure and stable thing. Culture is a shaky thing, which you have to uphold,” he said.

Cahan would know. He grew up in Antwerp, Belgium, speaking Yiddish at home. His parents were Holocaust survivors.

In the 1980s, he moved to Israel, where Hebrew is the predominant language. And he began collecting Yiddish books that people were throwing out. Now 52, he has piercing blue eyes, bushy eyebrows, and a receding mane of grey hair. He sings translated jazz standards like “Fever” in his band, Mendy Cahan & Der Yiddish Express. And he smokes Camels inside his dusty center, called Yung YiDish.

“My Yiddish books — I must say they survived gases, they survived ships and boats and sea and wars,” Cahan said. “And a little cigarette smoke will not hurt them.”

One day in 2013, Hungarian film director Laszlo Nemes walked into the library looking for help with Yiddish. It was for a film he was making that was set in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

“When I heard that he wants to make a Holocaust movie, I was hesitant,” Cahan said. “Like I said, no, another one is going to tackle the Holocaust in a movie? It’s true that I would rather not. I would rather we do something else, because it’s such a difficult subject. But when I saw his work and I saw his script, I understood he has here an opening which no one has tried.”

The movie tells the story of Saul, a Hungarian prisoner who escorts his fellow Jews into the gas chambers and then drags out the bodies.

For Cahan, Yiddish is a language of life. So translating the dialogue into Yiddish was an especially dark experience.

“Always when the theme of Holocaust just approaches, it’s kind of an elevator taking me down, and something forces me to stay there, to look as much as I can,” he said.

He also coached the Hungarian, German and Polish actors in Yiddish, mostly through months of training over Skype. He said the most difficult part was recording Yiddish for scenes of death in the movie, including the shouts victims would have let out from behind the doors of a gas chamber.

In early May, the Tel Aviv Cinematheque screened "Son of Saul" on Israel’s Holocaust Memorial Day.

Computer graphics designer Ruthie Vollweiter was there. Like most young Israelis, she doesn’t speak much Yiddish. She said Yiddish might have been the glue for European Jews from the past, but today, “it’s like a relic from a lost world, which is sad. It’s gone and we have Hebrew to glue us together now.”

Cahan says his life’s work is to make sure Yiddish is not forgotten, especially in Israel. He’s grateful for the chance to use Yiddish to make the Holocaust story more vivid. But he dreams of working on a film that depicts the rich world Yiddish speakers inhabited before the Holocaust.

“I think we should make an historical movie in Yiddish, which would be like in the 16th or 17th century,” he said. “This would be a beautiful movie showing the extent of Yiddish and you would have the different Yiddishes, and songs, and things. And we have novels we could base upon.”

It would be a movie most people would need subtitles to understand.