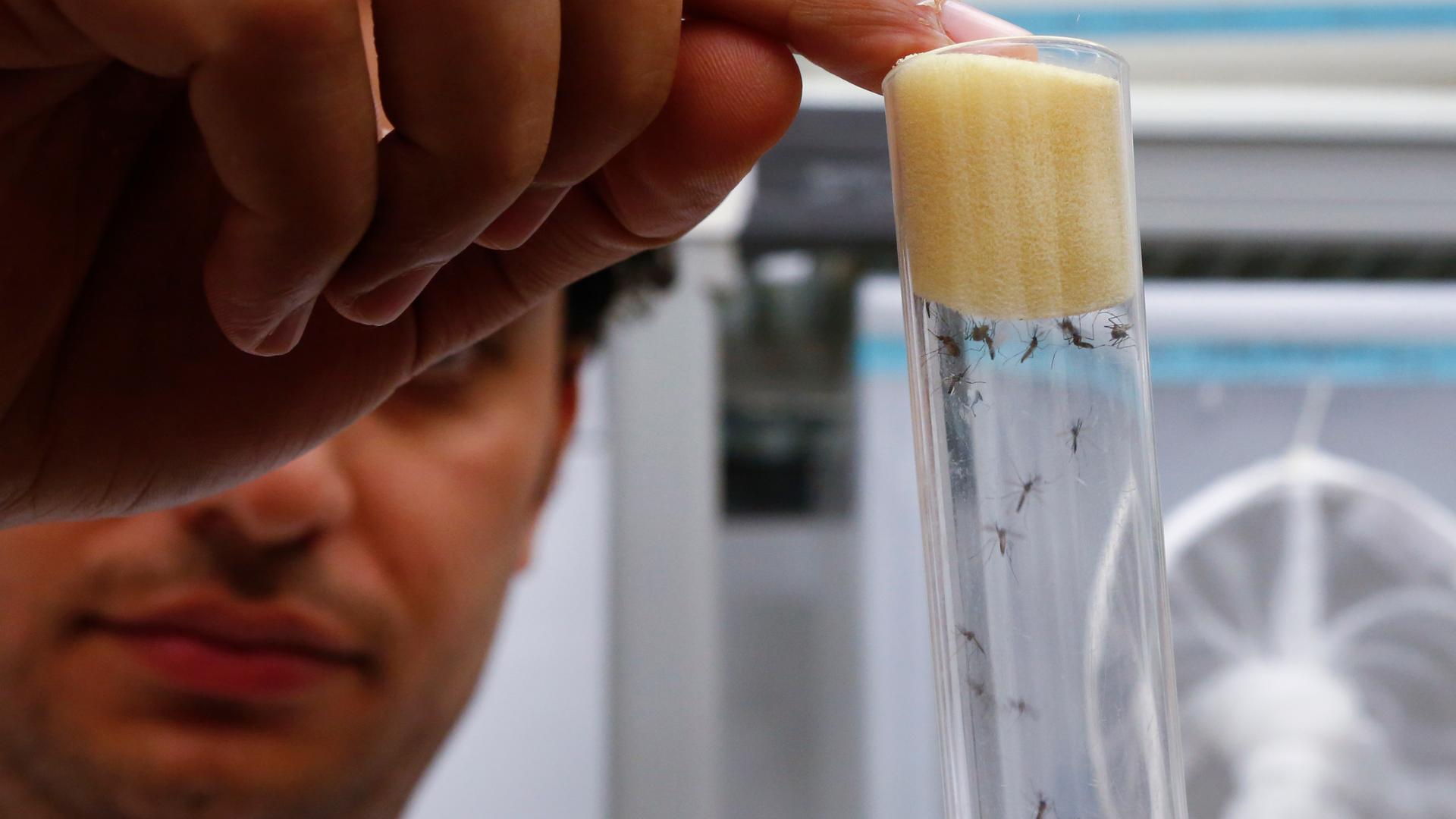

A scientist displays Aedes aegypti mosquitoes inside the International Atomic Energy Agency's insect pest control laboratory, Austria.

A pandemic is an epidemic gone global. Journalist and author Sonia Shah says humans' "disruption of wildlife habitat has been implicated in a number of new epidemics, from Ebola to West Nile virus and Lyme disease."

She says at this point, science and medicine react to epidemics, which means treatment comes after lots of cases are reported. The latest unnerving outbreak is the Zika virus.

"We wait for [viruses] to erupt, and then start scrambling to create drugs and vaccines to treat them," Shah says. "There won't be a vaccine for Zika for three to 10 years, by which time millions of people will have been infected."

But Christian Lindmeier, a spokesperson for the World Health Organization, says Zika has not yet been as lethal as other diseases.

“Zika is definitely very scary right now,” he says. “We don’t yet know what it’s responsible for, we don’t yet know if all the microcephaly cases … are caused by it, whether Guillain-Barre syndrome is caused by it, and that unknown is what scares people a lot.

“But in other terms, it doesn’t kill as many people as even malaria or dengue, so I think in numbers it’s definitely not ‘winning’, but in the scare factor right now, especially in the female child-bearing age population it is definitely ranking very high and its very understandable.”

Zika has been reported in 52 countries since 2007, including five where old outbreaks have already ended.

Guillain-Barre syndrome rates have risen in at least seven countries where Zika cases have been recorded, Lindmeier says.

Evidence that links Zika to microcephaly and severe mental handicaps in babies is not conclusive, but it is growing. Zika virus has been found in the amniotic fluid of babies born with microcephaly, and in the brain of a fetus with central nervous system abnormalities.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this month found that fetal abnormalities were detected by ultrasound in 12 out of 42 pregnant women in Brazil infected with Zika.

Larger comparative studies are tracking women in Colombia, where health officials were more prepared to study the disease when the outbreak arrived than they had been in Brazil. Results from those cohort studies are expected in May or June, Lindmeier said, and could help shed light on a number of questions, including how much Zika infection increases the risk of a pregnant woman giving birth to a baby with microcephaly.

“We need to establish, of course, could it be Zika alone which causes this,” Lindmeier said. “Could it be Zika with some other infection?”

As populations in South America get infected and develop immunity to Zika, infection rates and associated cases of microcephaly and Gullian-Barre syndrome are expected to peak and drop again, in a kind of wave.

“We don’t know yet how long these waves will last,” Lindmeier said, because it’s not yet know if immunity to Zika lasts for years or forever.

Shah, whose new book "Pandemic" explains the history of epidemics that have expanded throughout the globe, says medicine could evolve to be proactive in dealing with these diseases.

"If we expand our idea of health beyond biomedicine," Shah says, "we could start to address the underlying social and political conditions that fuel pandemics. As history has shown, pandemics are an outcome of human activities."

Shah goes back to the first cholera pandemic, which she says was caused by British colonization of the South Asian wetlands, "the cholera bacterium's natural environment."

"When we invade or disrupt wildlife habitat, we're forced into novel, intimate contact with animals — giving their microbes an opportunity to spill over and adapt to our bodies."

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!