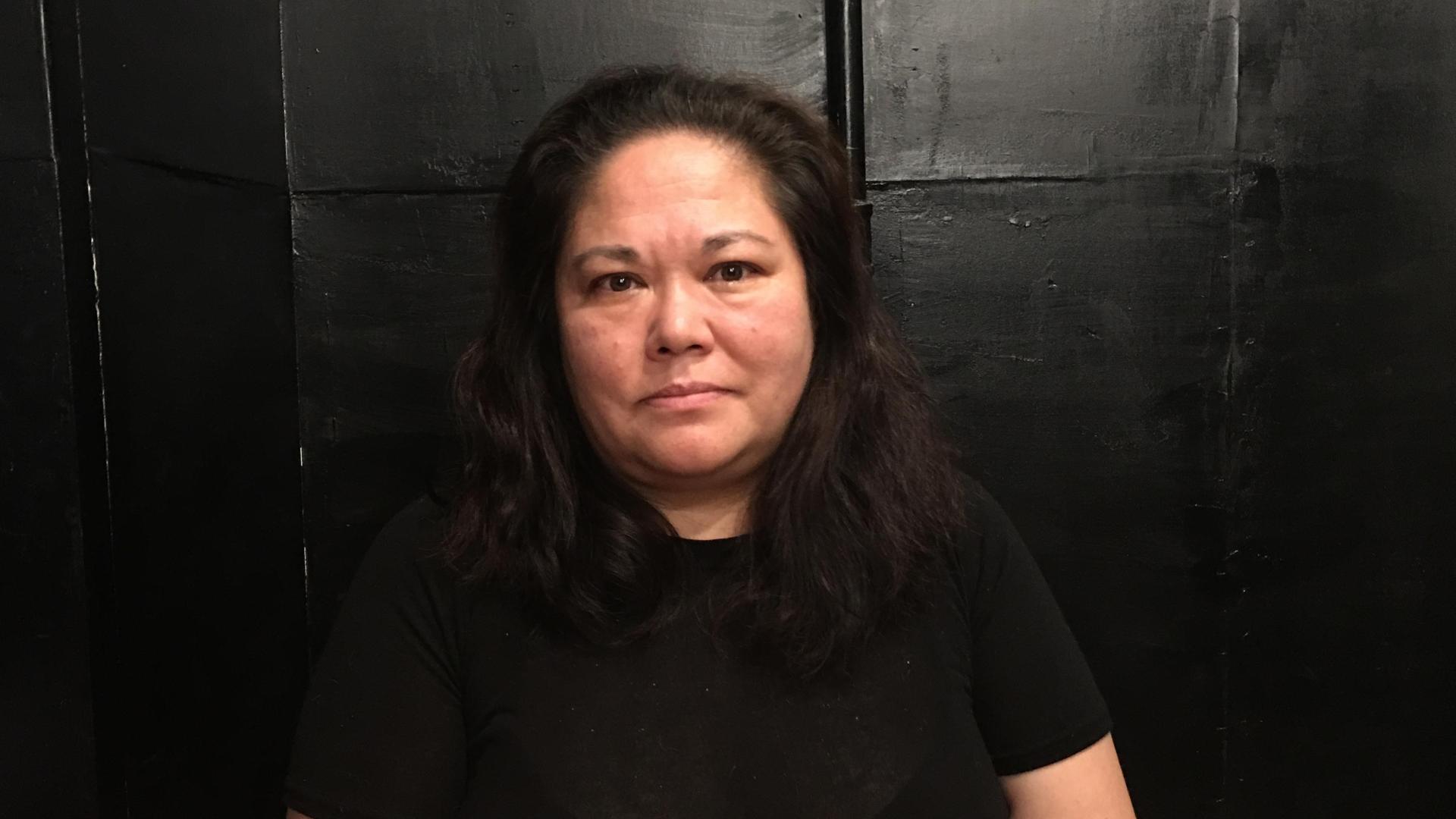

This woman has been stuck in Korea for three years trying to get home to the US

Kim Craig has spent the past three years in Korea, hoping to get home to the US.

Kim Craig was adopted at the age of 5 by a family in New Hope, Minnesota. On a recent fall day in a coffee shop in Seoul, she looked like any typical American tourist on vacation — no makeup, casual clothes. She ordered her coffee in English. But technically, Craig is not an American. She never received her US citizenship.

More than 160,000 children from South Korea have been adopted internationally since the 1950s. Most of the receiving countries conferred automatic citizenship, except for one: the United States. The process there created a loophole that left some adoptees without the rights they were supposed to receive. Last month, a Korean adoptee, Adam Crapser, lost his bid to stay in the US and is expected to be deported back to South Korea — a country he left nearly 40 years ago at the age of 3 — because he also never received citizenship.

Kim Craig’s troubles started with her unstable home life in the US.

She says her adoptive mother was abusive and gave her up after a year. Craig was then sent to live with another adoptive family in Minnesota, which didn’t work out either. She remembers having to project a certain family image, but she says it was a lie.

“I don’t have a lot of memories, other than maybe [events that took place] outside of the home,” she says. “Inside the home, very few except for getting beatings.”

“She said, 'well, you’re going to get what you want. We’re going to give up our rights… and oh, by the way, you’re not a citizen.' And at the time I didn’t know what that meant,” she recalls.

Although she was raised as an American — and even joined the military later — she wasn’t a US citizen. A loophole in US immigration law required adoptive parents to observe a several-year waiting period after an international adoption before naturalization could be finalized. Meanwhile, the Korean government would routinely cancel a child’s citizenship there. But some parents, like Craig’s, never completed the paperwork. It’s not known how many international adoptees in the US currently are without their citizenship; some advocates estimate it’s in the tens of thousands. The Korean government says the citizenship outcomes of as many as 18,000 adoptees to the US are unknown, though it admits to not keeping good data historically.

Craig says she once got close to acquiring citizenship on her own as an adult. After she enlisted, the military helped her fill out the paperwork. But she missed the swearing-in ceremony because she was shipped off to Germany before she got the notice to appear. And then there was another setback: Craig says she made a mistake and received a bad conduct discharge.

“As most things, I have a tendency to screw things up,” she says.

She returned to the States, where she worked and raised five children. She married, though she and her husband separated "fairly quickly." As a single mother, she says she was too busy to give much thought to ever returning to Korea to visit.

But a few years ago, one of her teenage daughters, a fan of K-pop, eventually won her over.

“She kept playing the music and it was driving me nuts. And I was like, ‘What are you listening to?!’ Actually I love [the K-pop band SHINee] now, they’re my favorite,” she says, chuckling at the memory. Craig liked one song in particular, “Please Don’t Go,” because it told a story of a lost love or separation. It reminded her of South Korea.

Her daughters wanted to learn more about their Korean background, so they persuaded Craig to take them to South Korea. She couldn’t get a US passport, but she found out that for $35 she could obtain a Korean one. So they went to Korea for a three-month visit.

Craig says from the start, she felt a jolt of recognition — familiar smells, familiar images. She saw the mountain ranges in the backdrop of Seoul and realized that mountains she would draw as a child in the US were actually from memories of South Korea.

And there was this: “First time in my life that I can remember walking [around] and I looked like everyone else,” she says.

Just as they were getting ready to go home, though, Craig lost her wallet. It had her US permanent residence card, which she had been told she would need to return. She says she went to the US Embassy in Seoul for help but they turned her away because she wasn’t a citizen. A week later, she went back.

“They tried to say the same thing. I said 'no, excuse me, it’s not my fault. I didn’t ask for this, I’m a permanent resident, you guys took me out of [South Korea], put me into this country [the US]. I only speak English, I can’t speak Korean; you guys have to help me.'”

Eventually someone listened and agreed to help, which is when Craig started to learn how complicated her situation might be. She couldn’t get her residence card replaced while outside the US. And without the card, she was told there was no guarantee she’d be let in.

Craig’s three-month trip to Korea has stretched into three years. She says it’s been hard for her to find work. Two of her kids are still here and they pitch in, but Craig is in debt. And she says she has a hard time fitting into Korean society.

“I try not to think about it on a daily basis that I just want to go home. But I can’t,” she says, holding back tears. “So I don’t think about it.”

Karen Christensen, who oversees citizen services for the US State Department at consulates around the world, says she couldn’t speak about Craig’s case but confirmed that immigration officials do have that final say over border entries. “That is actually technically correct [though] I don’t know how often that happens,” she said. Even if Craig entered as a visitor, she might jeopardize her status. Applying to replace a lost residency card when you’ve entered the US as a visitor could constitute fraud.

Christensen says she is sympathetic to the kinds of situations some adoptees have faced.

“They were brought [to the US] as children. I do understand it’s a difficult situation,” she said on a recent trip to Seoul. “These individuals … it wasn’t a failure on their part to take an action. I would suggest that if they are now adults that they approach the Depart of Homeland Security, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services and see about naturalizing in their own right.”

Yet it’s not so simple. Advocates say adult adoptees have no shortcut. They have to apply like any other immigrant seeking citizenship, and it can cost thousands of dollars in attorney’s fees and paperwork — not to mention a psychological toll and potential trauma of having to endure a process that should have been taken care of by their parents.

In 2001, the law changed so that foreign adoptees would automatically become citizens. But that didn’t cover those over 18 at the time, like Kim Craig, Adam Crapser, and many others. There is a proposal to fix that loophole.

For now, Craig continues to hope that she’ll get home one day and be reunited with her other three children, whom she hasn’t seen in all this time. But it will take money and possibly some help from US officials.

She says her kids and her anger keep her going.

This story has been edited from an earlier version. Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the type of military discharge Kim Craig received.