In San Lorenzo, California, on May 5, 1942. The last laundry drying in the sun before the mass removal of Japanese Americans during World War II. Famed Dust Bowl photographer Dorothea Lange documented the process of internment for the federal government.

In the late spring of 1942, The Andrews Sisters’ jaunty “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree” was on its steady rise to the top of the charts; the “taut and poignant” romance “This Above All” premiered in theaters; and winter crops were ripening to maturity in California’s sun-drenched fields.

But this was not your typical spring. This time of year, 74 years ago, America was at war. The December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and unrelenting waves of racist hysteria had cast citizens and immigrants of Japanese descent as “an enemy within.”

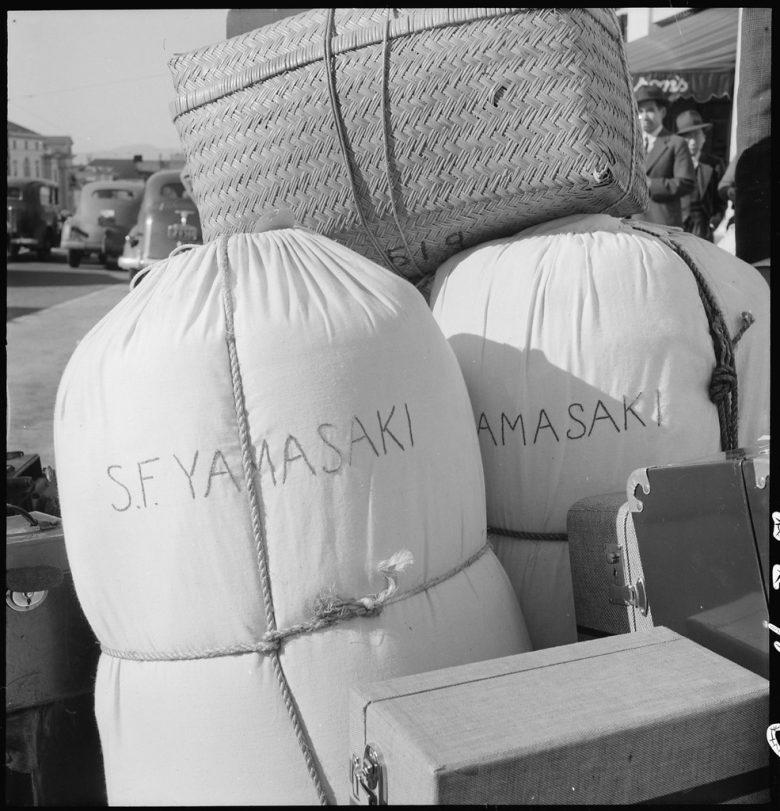

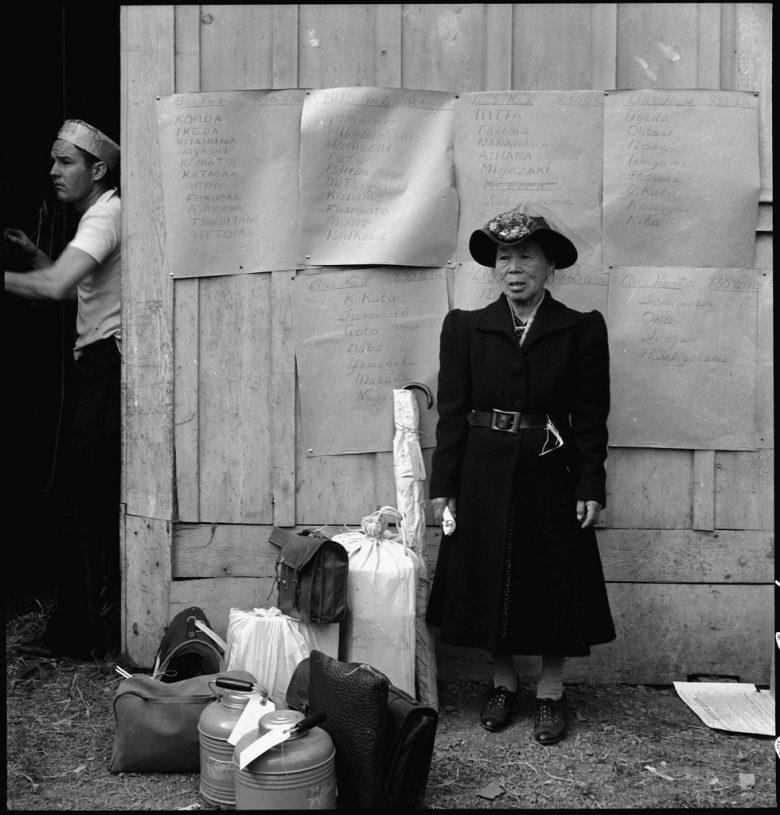

By April and May of 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s infamous Executive Order 9066 had begun to transform the West Coast. Lives were upended for the sole offense of having Japanese ancestry. Thousands were forced to pack up their belongings, board up their homes and businesses, abandon harvests and leave behind all that was familiar.

Our collective memory of this terrible moment in American history is informed by the incriminating visual record created by one woman: Dorothea Lange.

Famous for her forlorn images of Dust Bowl America, this pioneering female photographer was hired by the War Relocation Authority in 1942 to document the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

Although her skill at candid portraiture was unparalleled, “Lange was an odd choice, given her leftist politics and strong sympathy for victims of racial discrimination,” writes scholar Megan Asaka.

The position was a challenging one for Lange as well. “Appalled by the forced exile, she confided to a Quaker protester that she was guilt-stricken to be working for a federal government that could treat its citizens so unjustly.”

The WRA initially gave Lange little instruction about where and what to shoot, but controlled and censored her while she was at work. When documenting life inside the assembly centers and concentration camps, she was prohibited from taking shots of barbed wire and bayonets. Unable to tolerate this censorship and her own conflicted feelings about the work, Lange quit after just a few months of employment with the WRA.

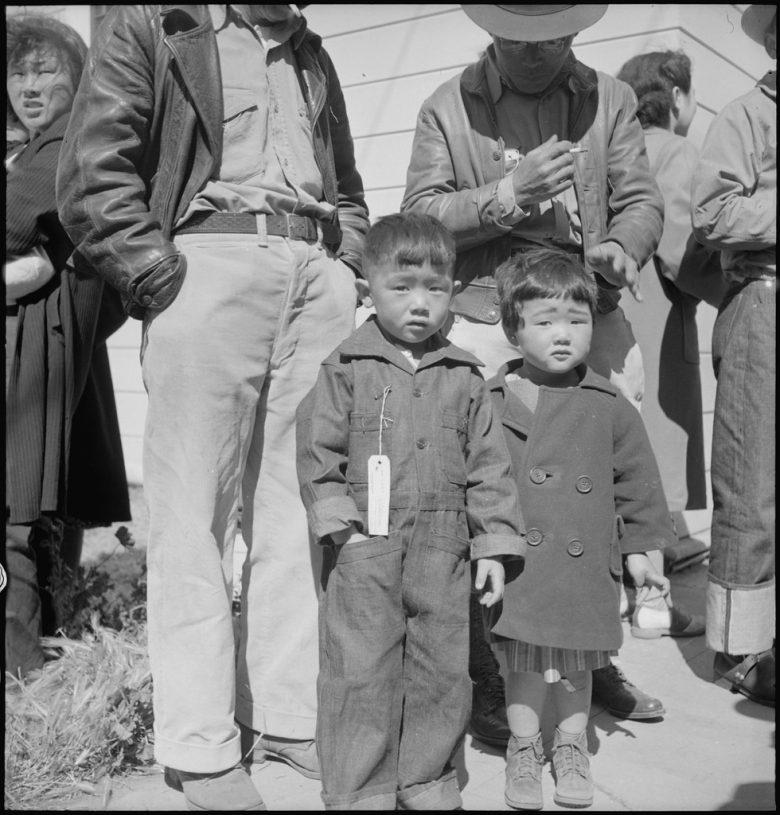

Even so, she managed to produce a body of work that at once captured the inhumane actions of the US government and the humanity of the individuals being forced to leave their lives behind for the “crime” of Japanese ancestry.

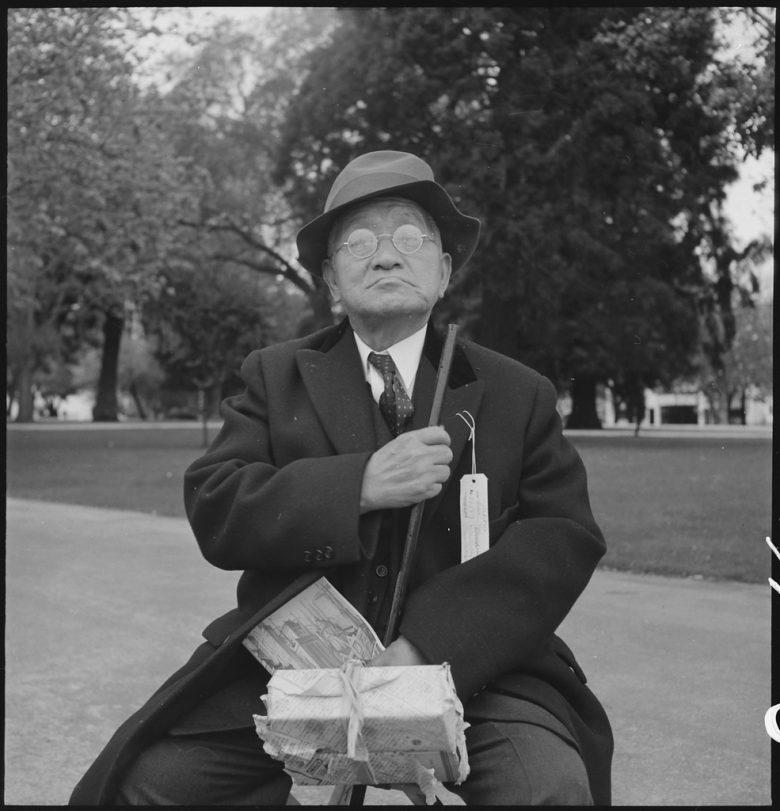

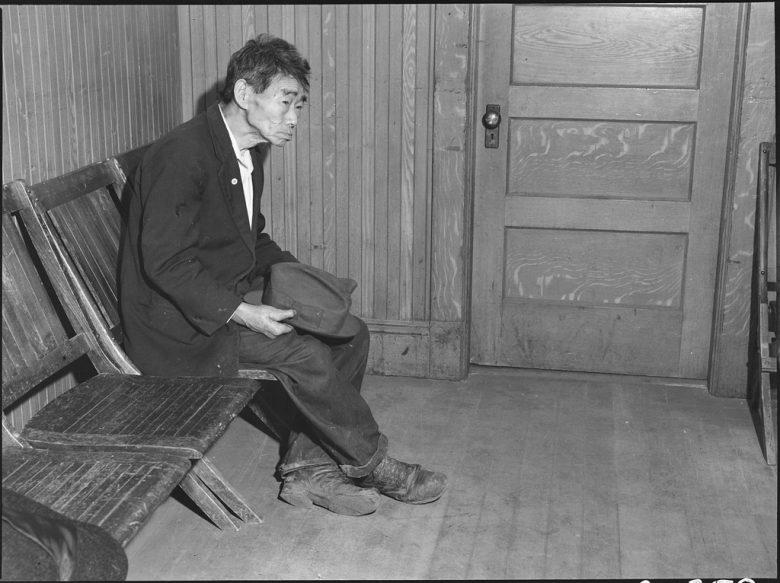

The stark vistas of Lange’s removal photos depict mundane worlds interrupted and preparation for the unknown: clothes left on the line to dry, urban streets crowded with suitcases and neatly packaged bedding, reluctant travelers wearing heavy winter coats on sunny spring days — not knowing where they were going or for how long.

The images transport viewers to the agonizing space between familiar homes and foreign prisons. They capture fear and defeat, but they also powerfully contest the government propaganda and hateful rhetoric aimed at vilifying Japanese Americans. Often shot from a low angle, Lange places her subjects on a visual pedestal. She restores some dignity in a moment when, many admit, they felt they had none.

The photos stand apart from Lange’s peers’. “In many of these photographs, what distinguishes Lange’s work from other WRA photographers is not only her habit of getting as close to her subjects as possible — her close-up portraits are often haunting whether individuals chose to return the gaze or not — but also her keen eye for ironic juxtapositions,” writes Elena Tajima Creef in “Imaging Japanese America.”

The federal government, quickly realizing that images of “enemy” infants and grief-stricken grandmothers would be bad PR, embargoed Lange’s photos for decades.

Finally, in 1972, the images were released and featured in the landmark traveling exhibition “Executive Order 9066.” Even all those years later, they had a profound impact. “Along with camp pilgrimages, political activism around the repeal of Title II, and a flood of new books, these exhibitions were part of the changing attitudes to the Japanese American wartime experience in the early 1970s that led to the Redress Movement of the 1980s,” writes Brian Niiya, editor of the Densho Encylopedia.

Lange’s exclusion-era photographs helped catalyze Japanese American activism in the 1970s, and they continue to shape the collective memory of one of the darkest moments in American history. The familiarity of urban vistas empower the viewer to empathize with the subjects, imagining ourselves in the shoes of the men, women, and children made to endure this terrible ordeal. They also serve as an impactful testament to the perils of racism and wartime hysteria.

Find more of Lange’s wartime photos in the Densho Encylopedia. Natasha Varner is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Arizona and communications manager for Densho, a Japanese American public history non-profit based in Seattle. This is an edited version of a piece that originally appeared at Densho.