As a kid, he fled Nazi Germany. As an adult, he found Hitler’s forgotten second book.

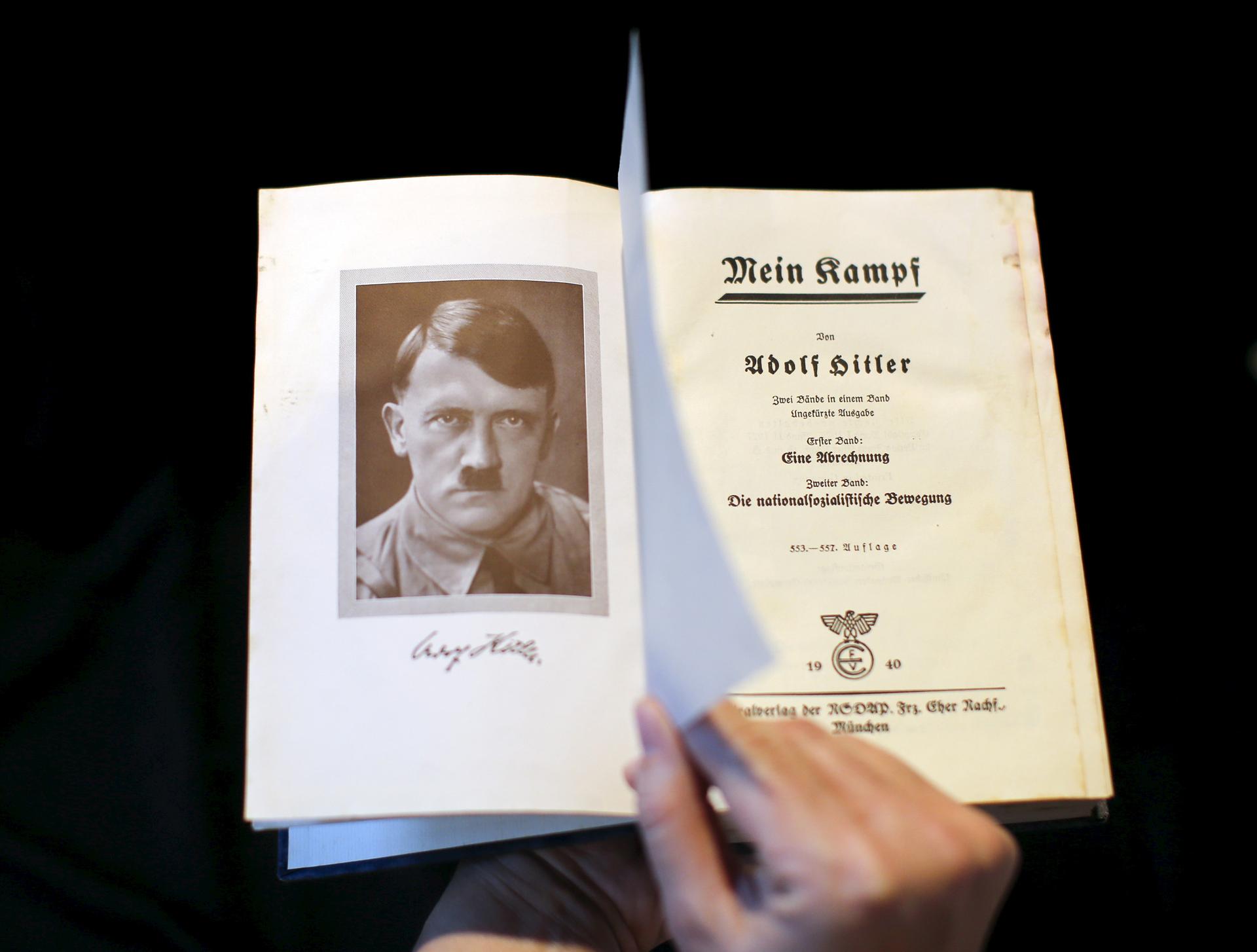

This copy of Adolf Hitler's book "Mein Kampf" (My Struggle) was printed in 1940.

Hitler’s book Mein Kampf has been infamous since World War II. But just recently, it became controversial again, thanks to a new German edition that comes out this month.

Mein Kampf wasn’t the only book Hitler wrote, however. In 1928, Hitler dictated a manuscript about Nazi foreign policy. It was kept hidden away — and it gathered dust for years after the war.

The man who finally unearthed Hitler’s second book is Gerhard Weinberg. He’s both a researcher and a survivor of Nazi Germany — and his experiences give him a unique perspective on the new annotated edition of Mein Kampf, set to publish later this year.

Weinberg, whose family is Jewish, was born in Hanover, Germany, and the Nazi Party came to power when he was 5. Weinberg remembers being forbidden from visiting restaurants and opera houses. “Kids at school would say to each other, you better behave, or you’ll go to the ‘KZ’! You’ll go to the concentration camp.”

In 1938, Jewish business and houses of worship were attacked. Weinberg had to walk past the scorched ruins of the local synagogue.

A year before war broke out, his family finally escaped. They settled in Albany, New York, and after the war Weinberg joined the US Army. That’s how he ended up becoming a historian: The GI Bill paid for his college education. “I was interested in history because of what I had seen and heard,” he says.

In the 1950s, Weinberg worked as an archivist in a former torpedo factory where the military stored World War II records. There he discovered references to a book by Adolf Hitler that he’d never heard of. That book ended up helping him become a renowned war historian.

“One day on my desk I had a folder listed as a partial draft of Mein Kampf,” he says. The moment he started reading, he saw that this was something else. It was Hitler’s manuscript on foreign policy.

Historians can learn a lot by reading both of Hitler’s books, Weinberg says. They show how the dictator’s ideology developed and evolved — and they help explain how and why World War II happened. For that reason, Weinberg says the new annotated edition of Mein Kampf will serve as an important tool for scholars.

German government officials originally tried to block publication of Mein Kampf. They said it would cause unnecessary pain for Holocaust survivors, and even suggested that it could fuel right-wing extremism.

But Weinberg sees things differently. He believes that reading Hitler could actually help prevent injustice in the future. “The Germans are not some separate species on Earth,” he says. “Other people might someday fall for something similar. We need to be rather careful.”

You can read Daniel’s full profile of Gerhard Weinberg at the website of the New Yorker.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!