‘They look at our children as monsters, and they’re not,’ argues mom of ISIS fighter

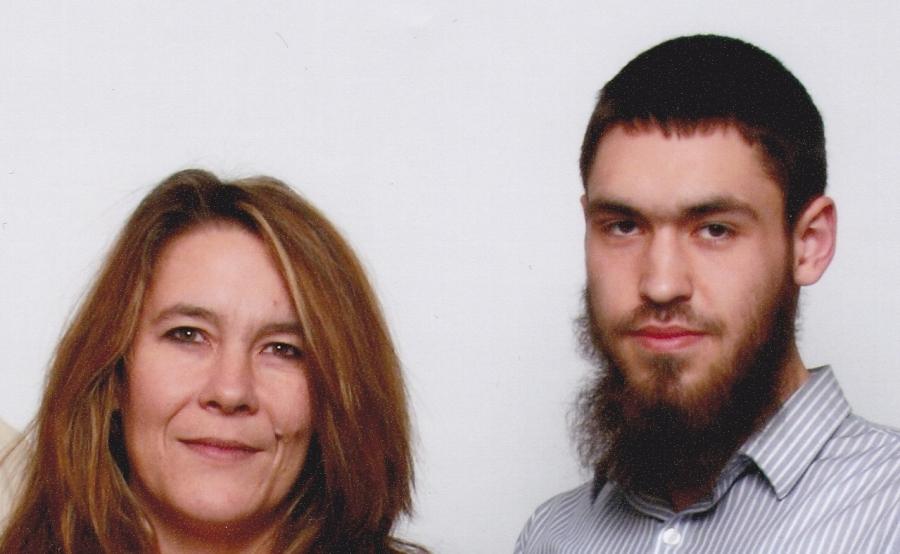

Christianne Boudreau lost her son Damian to ISIS. Now she's offering support to parents who've also lost their children to jihadi extremism.

What leads a young person, living what seems to be a "normal everyday life" in the West, to join an extremist group?

And what can you do to bring them back?

The BBC talked with one young British woman who was recently contacted by ISIS recruiters. She preferred not to use her name, but she did talk about what first got her interested in groups others might view as radical.

It was the news about three teenage girls, gifted students in east London who slipped away in February to join ISIS.

"Why are they going?" she asked herself. "I guess that sparked a sort of curiosity."

She started tweeting stories about the three girls. She thinks that ISIS recruiters found her Snapchat account in her Twitter bio.

"It wasn't really as cliché as people think it was. It wasn't a sort of 'Hey, come join us!'" she notes. "It was more of a, "Hey sister, how are you doin'?' … It's like a conversation with a friend. It's like a normal thing."

When the recruitment became more intense, she worried most about what joining a radical group would mean for her commitment to soccer.

"If I have three kids and a husband, am I really going to be able to continue living my passion?" she asked herself. "The thing about this [soccer] team is everyone's a family, everyone's together. You have somewhere where you are accepted, where everyone does love you. Once you have a place to go like this this, you won't even be brought to think about that kind of thing."

She now works with The Unity of Faiths Foundation, a group that fights radicalization through soccer.

In Canada, Christianne Boudreau co-founded another kind of group that works to counter extremism. It's called Mothers for Life, and it's a network for parents like her who have lost their sons and daughters to radical groups.

Boudreau's son Damian died fighting with ISIS in Syria last year. She's moving to France, and expects to find a stronger network of parents there looking to counter jihad.

"There are a lot more parents that have come open to one another, working together, supporting each other," she says. "Whereas in North America, very much there's still a stigma, everybody's holding back. They're afraid to speak out, they're afraid to reach out for help."

Boudreau says far too often parents miss the signs of radicalization, in part because popular portrayals of extremists lack nuance.

"They unfortunately look at our children as monsters, and they're not. They're normal, everyday kids that get caught up in something, make mistakes and don't realize the choices they're making," she says. "They're not all evil like what we see in the media. They're kids having emotional struggles."

When parents suspect their children are drifting toward radicalization, they should turn to others in their community for help, according to Boudreau.

"Parents shouldn't try to do this on their own," she says. "They're too emotionally connected to their children. And they can end up pushing their youth further away."

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?