The battlefields at Gettysburg have been getting an interesting makeover

For the past 15 years, the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania — the scene of the bloodiest fights of the US Civil War — has been undergoing major changes.

In the late 1990s, the National Park Service began to rehabilitate the natural landscape at Gettysburg, to make it look more like it did in July 1863, when the battles took place. In areas that saw heavy fighting, like the Peach Orchard, the Park Service decided to replant peach trees; in the meadows that had grown into forest since the battle, they removed the trees and restored the meadows.

In all, the Park Service has rehabbed more than 500 acres of the battlefield's most significant spots. They’ve also removed manmade structures, including a motel, a nine-hole golf course — even their own visitor center, which the Park Service plopped down in the 1960s at a key point on the Union line.

“We’re very careful about what we do and we base it on historic evidence and studies,” says veteran park ranger Katie Lawhon. “At the same time, our job is to preserve and maintain these battlefield features. We can’t be so in awe of the Gettysburg battlefield that we keep our hands off of it.”

Most of the heavy work is done now, but maintaining the battlefield's new look will be an ongoing process, because Gettysburg is still a living landscape that's constantly growing and changing — and nature doesn’t remember what it looked like in 1863.

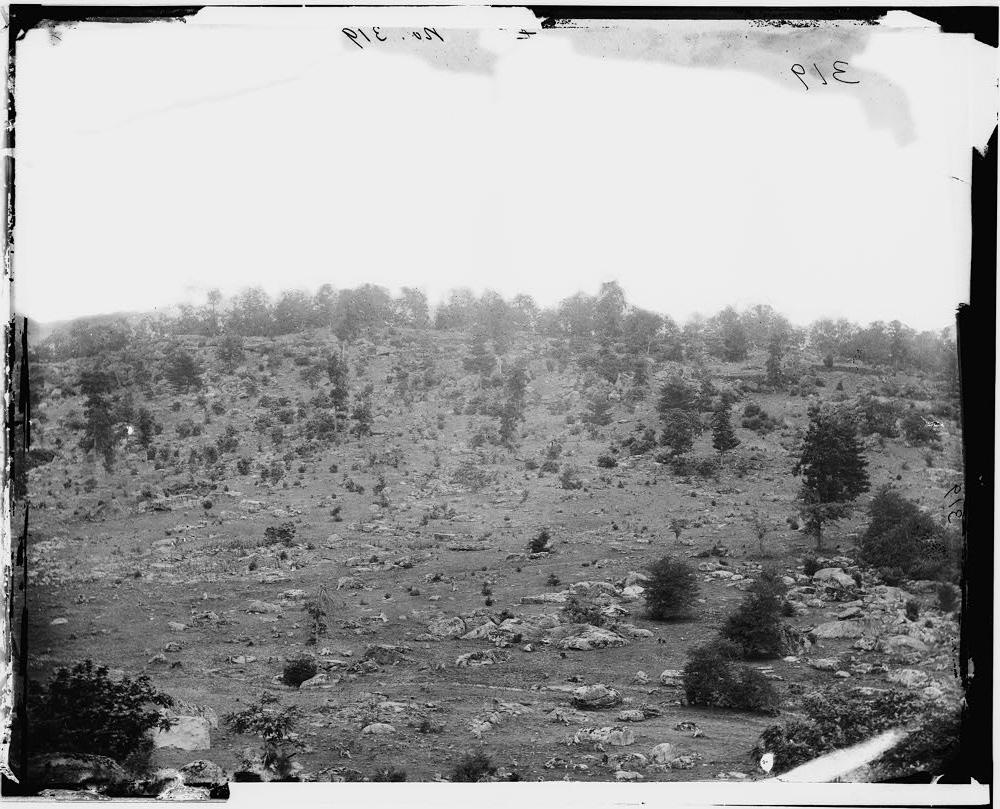

For example, Little Round Top, one of the most well-known sites at Gettysburg, was clear-cut of trees just before the battle. For historical accuracy, head landscaper Randy Hill has to maintain this clear-cut year after year or the trees will quickly grow back, changing the view of the battle scene.

Other natural details on the battlefield aren’t quite as authentic. The historic cluster of trees that was the focal point for Pickett’s Charge no longer has any trees dating back to 1863. So Randy Hill trims the existing trees to the right shape and size.

But one set of details the Park Service wants to make sure they get right is minimizing the environmental impact of the battlefield rehab.

“We knew that we wanted to remove up to 500 acres of wooded habitat, [but] we said, we’ll never do it in any one portion of the park all at once,” says Zack Bolitho, who manages natural resources at Gettysburg. “The thought process is that [birds and animals] will have the opportunity to adapt as we change the landscape.”

In an area called Devil’s Den, for example, they decided to leave some non-historic trees in place when they discovered they were home to a pair of nesting black vultures. And they mow fields as little as possible — and then only after Gettysburg’s birds are finished nesting. The Park Service has even started using controlled fire to mimic the way nature would regenerate the open meadows that are now once again part of the Gettysburg landscape.

“The Slyder field was our first 13-acre test burn,” Bolitho says. “And it was a pretty good success — success being that it was the first time we did it and people accepted that Gettysburg could burn and not burn down a cultural resource.”

The Park Service has done a pretty good job managing the environmental impacts, according to Randy Wilson, a professor of environmental science at Gettysburg College and an expert on public lands management.

“Gettysburg is a national military park, so its purposes and its reason for being wasn’t about protecting the flora and fauna so much as about the historical values that have to do with the Battle of Gettysburg,” Wilson says. “So their efforts to try to intervene and say, look, [this] can also be a place where we can protect the environment — I think that’s a very important step.”

This article is based on a story by Lou Blouin of The Allegheny Front that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.