New Orleans is still vulnerable to another big storm

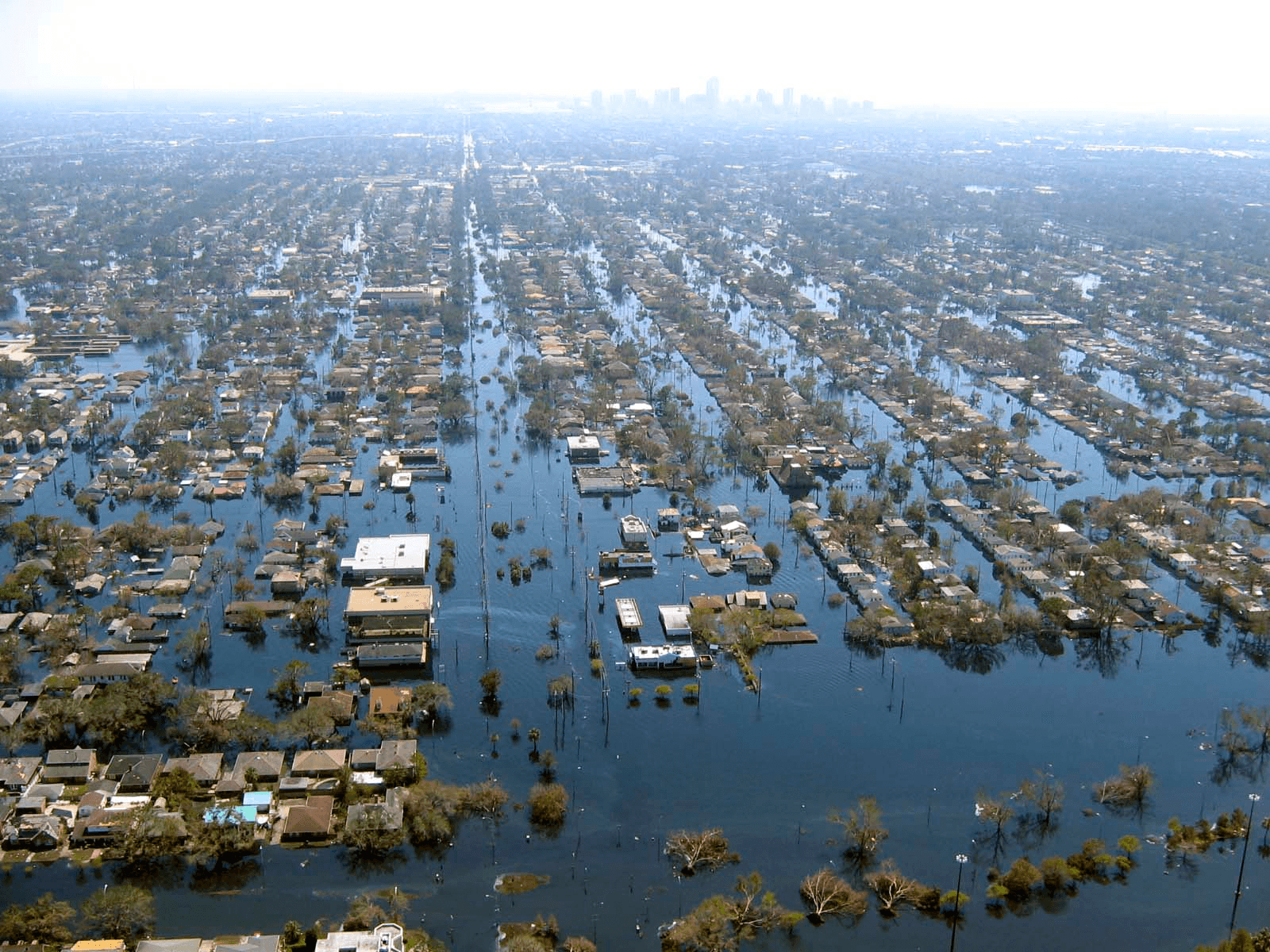

Hurricane Katrina flooding in New Orleans

As it approached New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina was one of the most powerful hurricanes ever recorded in the northern Gulf of Mexico. By the time it swept past the city and hammered the Mississippi coast, the storm had weakened.

Unfortunately, the defenses protecting New Orleans had also weakened. The result was a disaster of overwhelming proportions.

Ivor van Heerden, former co-director of the Hurrican Center at Louisiana State University, had been warning of the danger as early as 2001. He was also part of a team of experts who wrote a scathing report detailing the engineering deficiencies that had magnified the damage. For thanks, he was fired from his job at LSU and has since been virtually unemployable.

Was killing the messenger really the best response to the disaster? Obviously Van Heerden thinks not. And he still has one last message for New Orleans.

“The Dutch had their Katrina in 1957,” van Heerden points out, “and they recognized they had to retreat from some of the low-lying areas and then build a line of defense back from the shoreline. In Louisiana, that reality hasn't stepped in. [People] still hope that everything can be saved.”

The Army Corps of Engineers completed its rebuilding of the levee system on the Mississippi River in 2012 and van Heerden applauds the work, calling the repairs “robust.” “The existing systems were strengthened with concrete pads in front and concrete pads in the back, so they should be able to withstand a certain amount of over-topping,” van Heerden explains. “And they've closed the big navigation canal — the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet — which is a project that many of us have called for for many years.”

Nevertheless, van Heerden remains concerned. “The Corps of Engineers is claiming that Katrina is a one-in-400-year storm,” he says. “In reality, the statistic should be that Katrina is a one-in-30-year storm — and it was a storm that actually missed New Orleans.”

“If the levees had held, we wouldn't be talking about Katrina in Louisiana, we would be talking about the devastation on the Mississippi coast,” he explains. “Because the storm actually made landfall in Mississippi, not Louisiana. … Katrina might have been the trigger, but [in New Orleans] this was a man-made catastrophe.”

Van Heerden’s other major concern is the continued loss of wetlands in the Mississippi Delta. “In Louisiana, we’ve lost a millions acres of our coastal wetlands,” he says. “In many places there used to be cypress swamps, in others a rather healthy marsh. Just the presence of the vegetation removes energy from the wind and you get less surge, and as the surge moves through and over the vegetation, it loses a lot of its elevation due to the friction.”

Healthy wetlands are essential to softening the blow of a storm like Katrina. But the levees put up by the Army Corps of Engineers stopped the over-bank flooding of the Mississippi and the distribution of fresh water sediments and nutrients into the wetlands, van Heerden says, essentially starving them. Then, to add insult to injury, he adds, “we came along and cut them up for the oil and gas industry.”

“The sad reality is that the coastal land in Louisiana subsides about three feet every hundred years,” he explains. “Now, if you add to that the predictions for sea level rise, you’re talking about an effective rise in water of six feet over 100 years. So it's a losing situation unless you go in and try to restore the wetlands.”

Louisiana is going to have to make some hard decisions in terms of where they abandon areas and where they draw the line, van Heerden says. This may already be underway. “If you listen very carefully to the Corps of Engineers, they' no longer talking about ‘flood protection,’ they’re talking about ‘risk reduction,’” he points out.

When van Heerden was fired from LSU, he filed a lawsuit in federal court. At the eleventh hour, he says, the university offered him a settlement.

“I felt we had won a major moral victory and that hopefully LSU wouldn't do that again,” he says. “But the bottom line was I ended up being divorced from my science, from my students, [denied] access to supercomputers. And being damaged goods, I guess, I haven't really been able to find a job since. So my wife and I ended up taking early retirement.”

Van Heerden notes that while he lost his job for speaking out, “nobody from the Corps of Engineers even got rapped over the knuckles,” despite the overwhelming evidence that their design errors were largely responsible for the damage to New Orleans — errors that the corps itself eventually conceded.

In addition, LSU closed its hurricane center, which had generated so much of the data production and the map production during the response to Katrina. “So, not only did they do me a dirty, but they shut down one of the best things that existed at LSU,” van Heerden says.

As of now, the state university system has no center devoted to analyzing or predicting what might happen if another major hurricane strikes the area.

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?