Confirmed: The CIA’s most famous ship headed for the scrapyard

The CIA built the Hughes Glomar Explorer to retrieve a sunken Soviet nuclear submarine from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

The Hughes Glomar Explorer was more than just a giant ship — it was a giant secret, possibly the biggest and strangest covert operation the CIA pulled off during the Cold War. But now, 40 years after its original mission, it’s finally headed to the scrapyard.

The ship, now called GSF Explorer, had been retrofitted for oil drilling and exploration since it left US Navy service in 1997. But with the price of oil falling worldwide, its owner Transocean has decided to scrap it, along with several other vessels.

The ship’s origin story began in March 1968, when a Soviet Golf II class ballistic missile nuclear submarine, the K-129, sank in the Pacific Ocean. This was at the height of a high-risk cat-and-mouse game between the USA and the USSR. After the Soviet Navy failed to pinpoint the location of the wreckage, the US Navy found it. So the CIA decided to raise it off the seabed. They called this mission “Project Azorian,” and its details have been an official secret for decades. It took three years for retired CIA employee David Sharp to get permission to publish in 2012 his account of the mission and his role.

Sharp was at the engineering meetings where they tried to come up with a way to do what was at the time considered impossible, to pull up a huge object from an ocean depth of nearly 17,000 feet, or three miles.

“I think given a better background in marine engineering, we likely would not have tried” what they did, Sharp says. Luckily, the CIA also brought in skilled contractors like the deepwater drilling experts Global Marine (whose truncated name “Glomar” adorns the vessel).

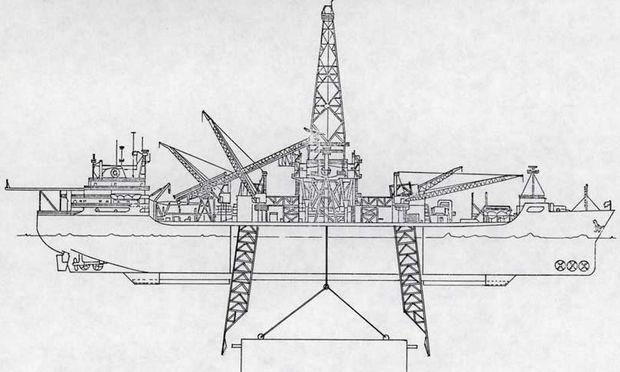

What they designed may never be seen again: The Hughes Glomar Explorer itself was massive — too wide to fit in the Panama Canal — and it was built to heave up and down on waves while its center held steady, lifting an enormous claw with the K-129 wreckage inside. Every piece of this hydraulic lifting apparatus was its own engineering nightmare, from the gymbals with bowling-ball-sized ball bearings, to the heave compensators and derrick that had to handle 14 million pounds of submarine, claw, and heavy pipe string. Lockheed engineers designed the “claw” itself, more accurately called a “capture vehicle,” and got it into the HGE via an elaborate submersible barge (echoes of which a few people detected during the 2013’s not-as-awesome Google Barge mystery).

It would be impossible for the US military to build such a huge and complicated ship, or to bring it out on the high seas, without getting the attention of the Soviets. Hence the true wonder of Project Azorian: its commercial cover story, one that puts the movie “Argo” to shame. From about 1970-74, the CIA managed to convince the world that billionaire inventor Howard Hughes had decided to invest millions to mine “manganese nodules,” balls of heavy metals that lie on the ocean floor. Via fake press releases, events, technical specs and front companies, the CIA convinced the world that Hughes was leading a new ocean-mining rush.

Other Hacker News: How Minecraft is changing education

In the end, the expensive mission was only a partial success: the ship’s lifting apparatus broke apart about 9000 feet below the surface, and the majority of the K-129 fell back to the floor of the ocean. It was impossible to retrieve without building a new claw, and before that could happen, details of the mission broke in the press. That didn’t stop the CIA from trying to keep it under wraps for as long as possible, leading to its notorious “Glomar Response” to Freedom of Information Act requests: the non-answer “we can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the materials requested.” That answer has held up in court over the decades and proliferated among federal and even local government agencies.

It was also the inspiration for the extra-dry humor of the CIA’s first tweet.

Hughes Glomar Explorer entered popular culture in other ways, as conspiracy theories have swirled around the K-129 and the mission to retrieve it. One of them is promulgated in the 2005 book “Red Star Rogue” by Kenneth Sewell and Clint Richmond. The book became the basis of the 2013 drama "Phantom," which features Ed Harris and David Duchovny as Soviet military officers who sip vodka in a very un-Russian way.

In 2006, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers declared Hughes Glomar Explorer an historic landmark. “Grasping and raising a 2,000-ton object in 17,000 feet of water in the central Pacific Ocean was a truly historic challenge, requiring a recovery system of unprecedented size and scope,” ASME wrote.

Americans can remember the whole affair for its daring, hubris, disappointment and secrecy. But for the loved ones of the Soviet sailors who died on the K-129, the words “Hughes Glomar Explorer” are more bitter. The Soviet government tried for 30 years to keep the fate of the submarine a secret from the families. After the USSR fell apart, both the Russian and US governments decided to make a clean slate of it, and then-US Defense Secretary Robert Gates delivered some of the intelligence on Project Azorian to the Russian government, along with artifacts from the chunk of the submarine the CIA managed to retrieve.

Gates also released a secret video of a funeral at sea for the remains of six Soviet sailors that were pulled up from the ocean floor. It remains one of the strangest artifacts of the entire Cold War — the other being ship itself, but it appears that one will not be with us for much longer.

Giant floating Museum of Secrecy, anyone?

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DkFWMo7aHDRo

Hear more of Julia Barton's reporting on the Hughes Glomar Explorer over at Radiolab from WNYC.