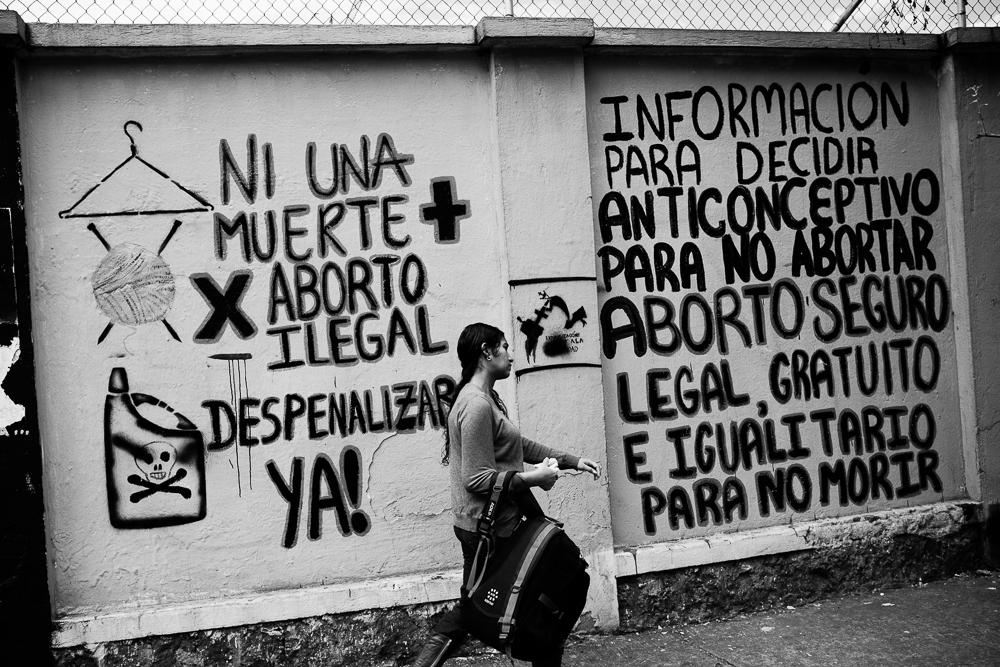

A woman walks past graffiti painted in downtown Quito, Ecuador, by abortion and birth-control advocates in 2014, at the height of a national debate over women’s reproductive rights.

Pope Francis is visiting Ecuador, among other Latin American countries. It's the first papal visit to Ecuador since the 1980s, and the country’s president Rafael Correa has been personally involved in planning for the past six months, tweeting about it enthusiastically.

Correa is known outside Ecuador for his investment in social programs and infrastructure. But many of his critics argue that his policies toward women are among the most conservative in Latin America. Women’s groups in Ecuador say they’ve been losing a series of hard-won rights since Correa first came into office in 2007.

Most recently, they’ve seen the dissolution of the government agency tasked with reducing teen pregnancy (also known as Estrategia Nacional Intersectorial de Planificación Familiar y Prevención del Embarazo en Adolescentes). Correa reorganized it late last year, and appointed an anti-abortion activist to run it. Mónica Hernández is associated with the conservative Opus Dei organization and is also a vocal proponent of abstinence.

“This has nothing to do with religion,” Hernández insisted soon after her appointment to the newly-named Plan Familia, a parent-education program pushing for abstinence. “We want everyone in Ecuador to have a right to define their family planning according to their own beliefs.”

The debate over family planning heated up one year after Correa came into office, in 2008, when Ecuador rewrote its constitution. In the new document, the government explicitly “recognizes and guarantees life from the moment of conception.” Then, last year, pressure from public health and gender rights activists led various assemblywomen to suggest a reform to the abortion law, asking for the procedure to become legal for all victims of rape. Speaking to the media before the vote, President Correa dismissed the effort as “a gay and abortionist agenda.”

“These days you’d think that saying you’re a heterosexual who believes in family, and in the Church, is a sin,” he said. “I won’t be ashamed for being a heterosexual male who believes in family and in the Catholic Church. But that’s the discourse we hear from protesters, which, by the way, isn’t shared by the majority of Ecuadoreans.”

As it turns out, the latest national survey from 2014 finds that about 65 percent of Ecuadoreans support decriminalizing abortion. On the other hand, more than 75 percent of Ecuadoreans self-identify as Catholic, a faith with a strong stance against abortion.

Last year, 29,000 teenage girls gave birth in Ecuador. Teen pregnancy rates are so high in Ecuador, that the topic is a common one for radio-novelas meant to bring sex education to the masses in an honest and straight-forward way — something that’s missing in the government’s new family planning program which advocates for abstinence until marriage.

The person behind many such public service announcements is Jose Ignacio López Vigil, a former Jesuit priest-turned radio host who’s openly critical of the power of the religious lobby on the state by groups such as the Opus Dei.

“If you’re a public official, you must respect secular public policies. But in Ecuador, public officials here still talk of the Bible and the crucifix,” said López Vigil, referring to Correa, specifically. “This is due to the influence of secret and very powerful Catholic sects that are wielding more and more influence on the Ecuadorean government.”

Vigil is referring to Opus Dei and other groups such as Tradición, Familia y Propiedad, which are linked to rightwing parties or causes throughout Latin America. All support a strong abstinence-only message for sex education.

Birth control is hard to come by in Ecuador — it isn’t widely available at pharmacies, and on the street, prices are highly speculative. Those who are most affected by this shortage and by abstinence-only messages are young, poor and indigenous women.

“If women had access to birth control, they wouldn’t get pregnant; and if they weren’t getting pregnant, they wouldn’t need to have abortions,” says Quito gynecologist Virginia Gomez de la Torre. “But there are many challenges to getting access to reproductive rights in this country.”

Twenty-five-year-old Veronica Vera agrees. She’s a leader with Salud Mujeres, a collective of young women who advocate for legal abortion. I meet her at an outdoor café in Quito; as we speak, the people seated in the nearby tables stare at Vera as she speaks. She’s said aborto, the Spanish word for “abortion,” out loud, something of a taboo here.

But Vera is actually explaining how her group has made great strides on the debate over reproductive rights: People are more accepting of it, she says, and Salud Mujeres now runs a hotline to make misoprostol, a pill that induces early-term abortions, more accessible. Through the hotline, Salud Mujeres helps women find the pill and guides them through the process of terminating their own pregnancies in a safe manner.

“Since we started the fight six years ago with our abortion hotline, public opinion has really shifted,” said Vera, quoting the latest survey showing 65 percent support for decriminalizing abortions. “I think people in Ecuador are more willing to listen to other arguments regarding abortion, beyond the religious one.”

Still, when asked whether her activism for women’s rights has changed her views of Catholicism or the Pope, Vera couldn’t come up with the right words easily. “No,” she simply replied. “Just because we support abortion doesn’t mean many of us aren’t people of faith.”