Will Icelanders one day ditch their language for English?

Ari Páll Kristinsson is in charge of language planning at the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, the Icelandic government's language research agency.

Jón Gnarr is best known as the comedian who became the mayor of Reykjavik.

He’s also a great lover of the Icelandic language — and he fears for its future.

“I think Icelandic is not going to last,” says Gnarr. “Probably in this century we will adopt English as our language. I think it’s unavoidable.”

This is not an outlier view. Some linguists believe it is a distinct possibility that Icelandic will lose out to English. Among them, Ari Páll Kristinsson who is in charge of language planning at the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, the Icelandic government's language research agency.

“English is everywhere now, from the moment we wake up until we die,” says Kristinsson.

He means that quite literally. Births take places with the aid of medical devices whose instructions are in English, so hospital staff must be able to read English. And at funerals, Kristinsson says, friends and family often remember their loved one with songs sung in English.

It’s a big deal for any linguistic group to witness the marginalization of their mother tongue. It’s especially poignant for Icelanders.

Consider this survey devised by Zuzana Stankovitsova, a Slovak who has lived in Reykjavik for the past few years, studying the Icelandic language. She sensed that Icelanders had unusually strong feelings about their language. To test this, she asked Slovaks and Icelanders to define their nationality.

Most of the Slovaks said, “I am Slovak because my parents are Slovak.” Or, “I am Slovak because I was born in Slovakia.”

Icelanders responded differently. Usually, along the lines of, “I am Icelandic because I speak Icelandic.”

Land, Nation and Tongue

Most adult Icelanders recall singing a song at school called “Land, Nation and Tongue.” It’s based on a poem by Snorri Hjartarson, written in 1952 when Iceland was a new nation.

“Land, nation and tongue was a divine trinity — not the divine trinity. But on a similar level as that,” says Kristinsson. He says this patriotic belief was instilled in him as a child.

“If we lost the Icelandic language, there would be no Icelandic nation,” says Kristinsson. “And if there’s no Icelandic nation, there is no Icelandic sovereignty.”

Iceland only won full independence, from its colonial master Denmark, during World War II. The divine trinity was finally in place. But almost immediately there was a challenge to the language, though not recognized at the time. It came in the form of 40,000 US troops who were stationed in Iceland during the war. The US military didn’t completely leave until 2006.

By then, most Icelanders spoke fluent English alongside their native tongue.

Urbanization, air travel, satellite TV, and the Internet have all followed. Every nation has been changed by these things. But Iceland arguably more so, more quickly. Gone was the isolation that had done so much to protect the language.

“When I was growing up, very few people spoke English,” says Gnarr. “With my generation, through TV and music it became necessary to understand English.”

Gnarr’s children speak much better English than he does. They have friends all over the world who they converse with on social media.

“But they don’t speak as good Icelandic as I do,” says Gnarr. “It’s a drastic change in a very short time.”

“I think that people, especially older people, are very skeptical of the use of the English,” says Larissa Kyzer, an American who lives in Reykjavik and studies Icelandic.

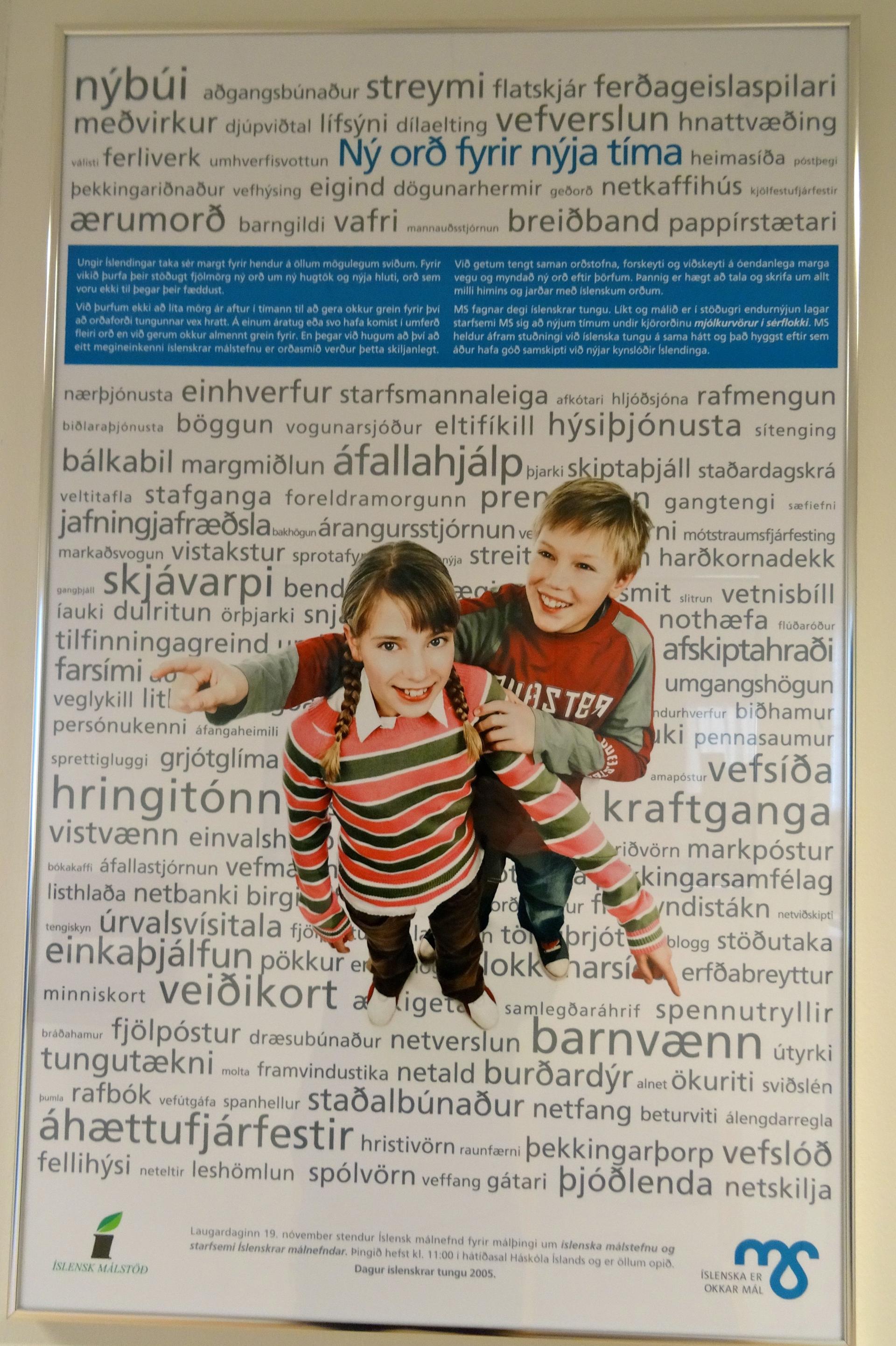

Kyzer has noticed a big push to make Icelanders proud of their language. “The afterschool program where I work has all these posters up on the wall now: ‘Icelandic is our mother tongue,’” she says. “I had a teacher who would [tell] her children, she said they could swear all they wanted as long as they used Icelandic swearwords.”

Where is Icelandic headed?

There are several possibilities for the future of Icelandic. Here are two.

The first draws on Icelanders’ reverence for storytelling, from the Sagas of Iceland’s early years to the extraordinary number of writers today. Some linguists believe that the tipping point for Icelandic — the moment when it may truly leave the hearts of Icelanders — would be when the country’s poets and novelists stop writing in Icelandic. Sverrir Norland has some experience of this.

To improve his writing, the young Icelander left his home country for a creative writing course in London.

“For obvious reasons, I had to write in English,” says Norland.

First it felt fake, but then liberating, which reminded him of a quote attributed to Bjork.

“She said something like, ‘When I first started singing in English I felt like I was lying.’” Says Norland. “That’s kind of terrible thing, but at the same time it’s kind of freeing. You can be whoever you want to be.”

You can even pretend you’re not Icelandic.

Norland didn’t go that far. In fact, today, he’s writing in Icelandic again. But would he ever write more fiction in English? Not out of the question, he says.

So that’s the first possibility — that some writers may switch to English, sending a powerful message to their readers in Iceland.

Here’s the second, rosier possibility: Immigration may give Icelandic a boost.

“I’m more Icelandic perfect, not English,” she says. Just like her Icelandic husband. They speak to each other in Icelandic. Kahssay is probably the world’s only Ethiopian who speaks better Icelandic than English.

“I’m looking very much forward to the time when immigrants start to write literature in their version of Icelandic — creating new words, says novelist, Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir. “That’s how language should be: Alive, creative, inventive.”

Just like the language of the Sagas many centuries ago, says Ólafsdóttir. She is fluent in several languages but says she would only ever write in her mother tongue. “I think that the world needs stories that are told in Icelandic.”

Which is what Ólafsdóttir does. Two of her novels are translated into English. One of them, “Butterflies in November,” is a funny, sad, unsentimental mock-epic. You feel the influence of the Sagas.

Sverrir Norland, the writer who has written in English but now is back writing in Icelandic, believes the Icelandic identity comes with writing and speaking the language.

“If I’m telling the story in Icelandic I’m thinking about Icelandic readers, and I’m assuming they share a similar experience and knowledge about the stuff I’m talking about,” says Norland. “But if I’m writing in English about Icelandic people, I would be explaining all kinds of different things — so it would turn out very differently.”

This is the second of two podcasts on Icelandic. Check out The future of the Icelandic language may lie in its past.