No longer mayor of Reykjavik, Jón Gnarr can restart his career as a comedian. Not that he ever stopped

Reykjavik mayor Jón Gnarr decked out as Obi-Wan Kenobi at a political event in Reykjavik, Iceland.

On the night he was elected mayor of Reykjavik in June 2010, Jón Gnarr gave his supporters a taste of what might be to come.

“Welcome to the revolution!” he declared. Like much of what he says, it was tongue-in-cheek. Maybe.

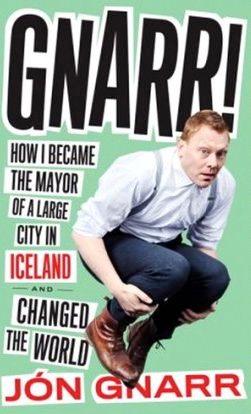

Four years later, Gnarr has retired, having served a single term. He’s written a book and is trying to figure out what to do next.

Gnarr used to be a punk rocker — an anarchist too, and one of Iceland’s best-known comedians. His campaign for mayor was an extended piece of performance art that morphed into a real-life show, “right after I got elected,” he says.

He became mayor at a time of desperation for many of Reykjavik’s residents. The 2008 global meltdown had hit Iceland harder than just about anywhere else. Three major banks had collapsed, the government was bankrupt and overnight, people found themselves knee-deep in debt, their savings wiped out.

So they voted for a man who made ridiculous campaign promises that no-one expected him to keep: promises about additions to the city’s zoo and swimming pools, and most poignantly, a pledge to eliminate all debt.

So they voted for a man who made ridiculous campaign promises that no-one expected him to keep: promises about additions to the city’s zoo and swimming pools, and most poignantly, a pledge to eliminate all debt.

Gnarr’s political party — a new one — was made up mainly of artists and musicians: Besti flokkurinn means “Best Party.” Part of the name’s appeal was the pun in English (“I was at the best party last night”). The wordplay doesn’t work in Icelandic, but Gnarr says most people got the joke anyway.

Once elected, Gnarr immediately ran into problems. There were insults from real politicians, who told him he was “incapable of doing my job, I’m not qualified, and I’m a clown.”

They tried to show him up, Gnarr says, by using the densest possible bureaucratese.

“I mastered the Icelandic language very well; I’m very good at Icelandic,” he says. “But in Iceland, like in many other countries, the political culture has evolved into some sort of subculture with a different language. They have terms and words that ordinary people just don’t understand.”

Gnarr and his Best Party colleagues countered this way of talking by satirizing it — to the point of absurdity.

They came up with fake initiatives — outrageously condescending ones that were supposed to show how much they cared about certain groups, like the disabled and women.

“I openly said that we were willing to listen to women, and that we would even have meetings with women,” says Gnarr, fighting laughter. “We would record everything that they would have to say, so that future generations could listen to it.”

Gnarr knew he was treading a fine line, but most people seemed to get what he was up to.

“Sometimes I would sound ridiculous, but I’m harmless,” he says.

There are some of Reykjavik’s residents who wanted him to be a little less harmless, a little more Rage Against the Machine.

But that was never Gnarr’s revolution. Yes, he was tapping into the outrage at the political and business cabal that had ruled Iceland. His response was to poke fun at it — to show it up as irresponsible — and leave Icelandic voters in a better position to make more informed choices next time.

But that was never Gnarr’s revolution. Yes, he was tapping into the outrage at the political and business cabal that had ruled Iceland. His response was to poke fun at it — to show it up as irresponsible — and leave Icelandic voters in a better position to make more informed choices next time.

And, funnily enough, this anarchist high-school dropout is now regarded as having brought much-needed stability to the mayor’s office.

He generally didn’t interfere with the day-to-day running of Reykjavik — he left that to city managers. Instead, he pushed hard on issues like gay rights and improving public spaces, while also overseeing painful budget cuts.

Most refreshing for many was his refusal to run for a second term.

Leaving politics has allowed Gnarr to write a book and visit the United States. His first time in the US was in 1989. People would ask where he was from. His reply didn’t help. “They didn’t have a clue — they didn’t know what Iceland was,” he says. “But nowadays when I’m somewhere and being asked where I’m from and I say Iceland, and people say ‘Ah! Björk.’”

Björk, perhaps inevitably, is a close friend of Gnarr’s. And as well-known as she is around the world, Gnarr is also also becoming a sort of global cultural ambassador for Iceland.

He jokes that the country should rename itself Björkland, in recognition of its artistic riches.

“Once I was in a radio debate with the former mayor, and she said that we were just a bunch of artists,” he says. “She spoke of artists like some sub-humans, like people who can’t pay their bills or organize their daily life or something. That made me very angry. And I said what is this country of ours famous for if not for art and artists? From the very beginnings with the Sagas, and now especially with music, Iceland is world-known for its music and its musicians.”

It’s not clear even to Gnarr what’s next for him. He says he’s still trying to make sense of his four years in power.

He’s none too happy with the results of Reykjavik’s recent elections. Young voters stayed away from the polls, his political allies didn’t do well, while a party that opposes the construction of what would be Reykjavik’s first mosque did do well.

Gnarr’s only plans for now are, as you might expect, out of left field.

“I will definitely go to Texas,” he says. “But I’m not sure what I’m going to do there. I have noticed that many of my followers on Facebook are from Texas. So I’ll definitely have to go there and talk to the Texans.”

Sitting mayors in the Lone Star State facing re-election: you have been warned.

Click the audio button at the top of this post to hear a great conversation with Jón Gnarr, including the story of his name: he was born Jón Gunnar Kristinsson — and that's still the name on his passport. The Icelandic government refuses to recognize Gnarr, which it says is not a traditional Icelandic surname.

The World in Words podcast is on Facebook and iTunes.

On the night he was elected mayor of Reykjavik in June 2010, Jón Gnarr gave his supporters a taste of what might be to come.

“Welcome to the revolution!” he declared. Like much of what he says, it was tongue-in-cheek. Maybe.

Four years later, Gnarr has retired, having served a single term. He’s written a book and is trying to figure out what to do next.

Gnarr used to be a punk rocker — an anarchist too, and one of Iceland’s best-known comedians. His campaign for mayor was an extended piece of performance art that morphed into a real-life show, “right after I got elected,” he says.

He became mayor at a time of desperation for many of Reykjavik’s residents. The 2008 global meltdown had hit Iceland harder than just about anywhere else. Three major banks had collapsed, the government was bankrupt and overnight, people found themselves knee-deep in debt, their savings wiped out.

So they voted for a man who made ridiculous campaign promises that no-one expected him to keep: promises about additions to the city’s zoo and swimming pools, and most poignantly, a pledge to eliminate all debt.

So they voted for a man who made ridiculous campaign promises that no-one expected him to keep: promises about additions to the city’s zoo and swimming pools, and most poignantly, a pledge to eliminate all debt.

Gnarr’s political party — a new one — was made up mainly of artists and musicians: Besti flokkurinn means “Best Party.” Part of the name’s appeal was the pun in English (“I was at the best party last night”). The wordplay doesn’t work in Icelandic, but Gnarr says most people got the joke anyway.

Once elected, Gnarr immediately ran into problems. There were insults from real politicians, who told him he was “incapable of doing my job, I’m not qualified, and I’m a clown.”

They tried to show him up, Gnarr says, by using the densest possible bureaucratese.

“I mastered the Icelandic language very well; I’m very good at Icelandic,” he says. “But in Iceland, like in many other countries, the political culture has evolved into some sort of subculture with a different language. They have terms and words that ordinary people just don’t understand.”

Gnarr and his Best Party colleagues countered this way of talking by satirizing it — to the point of absurdity.

They came up with fake initiatives — outrageously condescending ones that were supposed to show how much they cared about certain groups, like the disabled and women.

“I openly said that we were willing to listen to women, and that we would even have meetings with women,” says Gnarr, fighting laughter. “We would record everything that they would have to say, so that future generations could listen to it.”

Gnarr knew he was treading a fine line, but most people seemed to get what he was up to.

“Sometimes I would sound ridiculous, but I’m harmless,” he says.

There are some of Reykjavik’s residents who wanted him to be a little less harmless, a little more Rage Against the Machine.

But that was never Gnarr’s revolution. Yes, he was tapping into the outrage at the political and business cabal that had ruled Iceland. His response was to poke fun at it — to show it up as irresponsible — and leave Icelandic voters in a better position to make more informed choices next time.

But that was never Gnarr’s revolution. Yes, he was tapping into the outrage at the political and business cabal that had ruled Iceland. His response was to poke fun at it — to show it up as irresponsible — and leave Icelandic voters in a better position to make more informed choices next time.

And, funnily enough, this anarchist high-school dropout is now regarded as having brought much-needed stability to the mayor’s office.

He generally didn’t interfere with the day-to-day running of Reykjavik — he left that to city managers. Instead, he pushed hard on issues like gay rights and improving public spaces, while also overseeing painful budget cuts.

Most refreshing for many was his refusal to run for a second term.

Leaving politics has allowed Gnarr to write a book and visit the United States. His first time in the US was in 1989. People would ask where he was from. His reply didn’t help. “They didn’t have a clue — they didn’t know what Iceland was,” he says. “But nowadays when I’m somewhere and being asked where I’m from and I say Iceland, and people say ‘Ah! Björk.’”

Björk, perhaps inevitably, is a close friend of Gnarr’s. And as well-known as she is around the world, Gnarr is also also becoming a sort of global cultural ambassador for Iceland.

He jokes that the country should rename itself Björkland, in recognition of its artistic riches.

“Once I was in a radio debate with the former mayor, and she said that we were just a bunch of artists,” he says. “She spoke of artists like some sub-humans, like people who can’t pay their bills or organize their daily life or something. That made me very angry. And I said what is this country of ours famous for if not for art and artists? From the very beginnings with the Sagas, and now especially with music, Iceland is world-known for its music and its musicians.”

It’s not clear even to Gnarr what’s next for him. He says he’s still trying to make sense of his four years in power.

He’s none too happy with the results of Reykjavik’s recent elections. Young voters stayed away from the polls, his political allies didn’t do well, while a party that opposes the construction of what would be Reykjavik’s first mosque did do well.

Gnarr’s only plans for now are, as you might expect, out of left field.

“I will definitely go to Texas,” he says. “But I’m not sure what I’m going to do there. I have noticed that many of my followers on Facebook are from Texas. So I’ll definitely have to go there and talk to the Texans.”

Sitting mayors in the Lone Star State facing re-election: you have been warned.

Click the audio button at the top of this post to hear a great conversation with Jón Gnarr, including the story of his name: he was born Jón Gunnar Kristinsson — and that's still the name on his passport. The Icelandic government refuses to recognize Gnarr, which it says is not a traditional Icelandic surname.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?