Athiel Al-Yusif and his wife, Bushra Azouz, are Iraqi refugees with diabetes. In San Diego, where they now live, they've found help managing their disease through a diabetes class. The class meets at a nearby community clinic and is interpreted into Arabic.

Just a few months ago, Athiel Al-Yusif and his wife, Bushra Azouz, arrived in San Diego after fleeing northern Iraq. ISIS had threatened their family and their hometown. But they face another risk here in the US — diabetes.

They both have the disease, which, when uncontrolled, can lead to kidney failure, blindness and even amputations.

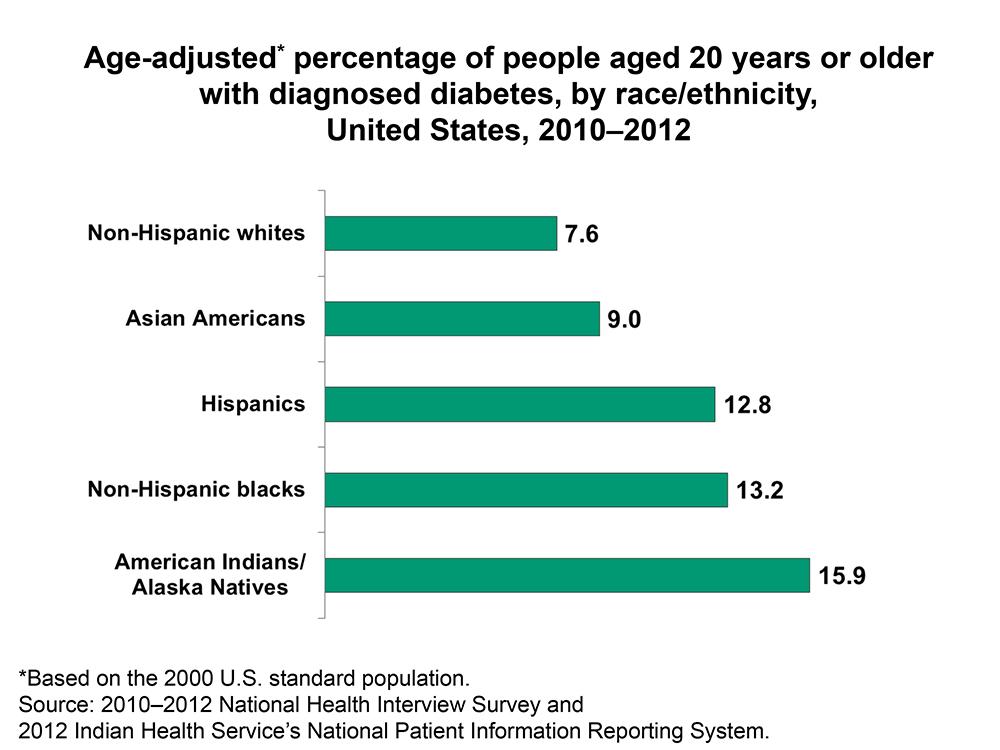

You probably know someone who’s diabetic, but if you’re an immigrant, you might know several people with the disease. Diabetes hits US immigrant communities especially hard, with genetics and higher-calorie diets explaining just part of it. To read more about this, there are studies here, here, and here.

Al-Yusif and Azouz joined a Project Dulce class with other Iraqi diabetics at a bustling community clinic in El Cajon. It’s a city near San Diego where many Iraqi refugees live.

“When I see other Iraqis sitting in class learning together, it keeps me encouraged,” Al-Yusif says. “I stay more on track."

That’s the hope. Imagine being new to America and its overwhelming health care system. Project Dulce holds immigrants’ hands as they deal with diabetes.

Alma Ayala, the instructor, is from Mexico and has diabetes, too. She shows the class how to give an insulin injection. She also passes around snacks — Greek yogurt and pita bread. It’s like hanging out in someone’s living room.

This feeling of being at home with people from your country seems to work well with this community. Al-Yusif says that, before signing up for the program, he didn’t think twice about eating the fatty meats he loved.

“I used to eat without instructions,” he says. “Now, I learned how to eat and how to use the needle test.”

He’s referring to pricking his finger to test glucose levels. His levels have normalized recently. “My blood sugar level was around 400, now it has reduced to 150-160. It’s a huge difference,” Al-Yusif says.

The program started by offering training in Spanish. The class for Iraqis is still fairly new and has just five students. The trick to increasing the number of Iraqi participants is getting the word out into the community — and securing more funding.

The students say they appreciate that their instructor is an immigrant with diabetes too. “When patients come to the class, and they know that I have diabetes, I right away connect with them,” Ayala says. “Just to know someone that has diabetes and can understand what you’re going through is very powerful.”

It’s a critical bond, says Tom Bodenheimer, a physician at the University of California—San Francisco. He’s extensively researched peer-to-peer diabetes coaching.

“People who speak different languages have not done very well with the US health care system,” Bodenheimer says. “Having part of their care done by other people who understand their culture and are a lot like them and are not intimidating, but are collaborative, that makes a huge difference.”

Chris Walker, senior director at Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, which hosts Project Dulce, explained how personalized and detail-oriented care transforms diabetic patients’ health.

“Before there was a Project Dulce, they’d come in, have a five-minute visit, get a medication, out they would go,” says Walker. “And there was nothing really in place that would work with them to change the behaviors, learn how to use the medication, get over some of the fear that patients had.”

Studies show the program’s approach works and doctors are seeing improvements across the board.

“We found in the studies that blood pressure, blood glucose and cholesterol all came down,” says Athena Philis-Tsimikas, a diabetes researcher who helped launch Project Dulce.

“Emergency room hospitalizations within a one-year time period were reduced,” she says, “and inpatient hospitalization costs were reduced."

After class, I visit Al-Yusif and Azouz at their small home near the clinic. Their two college-aged sons sit quietly on the couch and one holds prayer beads. Azouz says she’s more relaxed about diabetes now compared to when she was diagnosed in Iraq.

“I was so sad that I started to cry. I said to myself, ‘I have a dangerous disease and I’m going to die,’” she recalls thinking.

And then, when ISIS terror threats forced her to leave Iraq, Azouz fell into a depression. “It’s difficult to remove a tree out of its roots and then plant it in a different, far away land,” she says. “You either live or die.”

She started going to the diabetes classes alone, at first. Then her husband joined her. I ask him what he eats nowadays and he proudly opens up his fridge and rummages through bags full of veggies. He pulls out turnips, garlic, onions and more.

Back at the classroom, Ayala closes the eight-week program by awarding each participant a certificate. Everyone poses for a group photo. But now that the class is over, the challenge is to keep up what they’ve learned.

Sonia Narang reported this story with support from the Solutions Journalism Network.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!