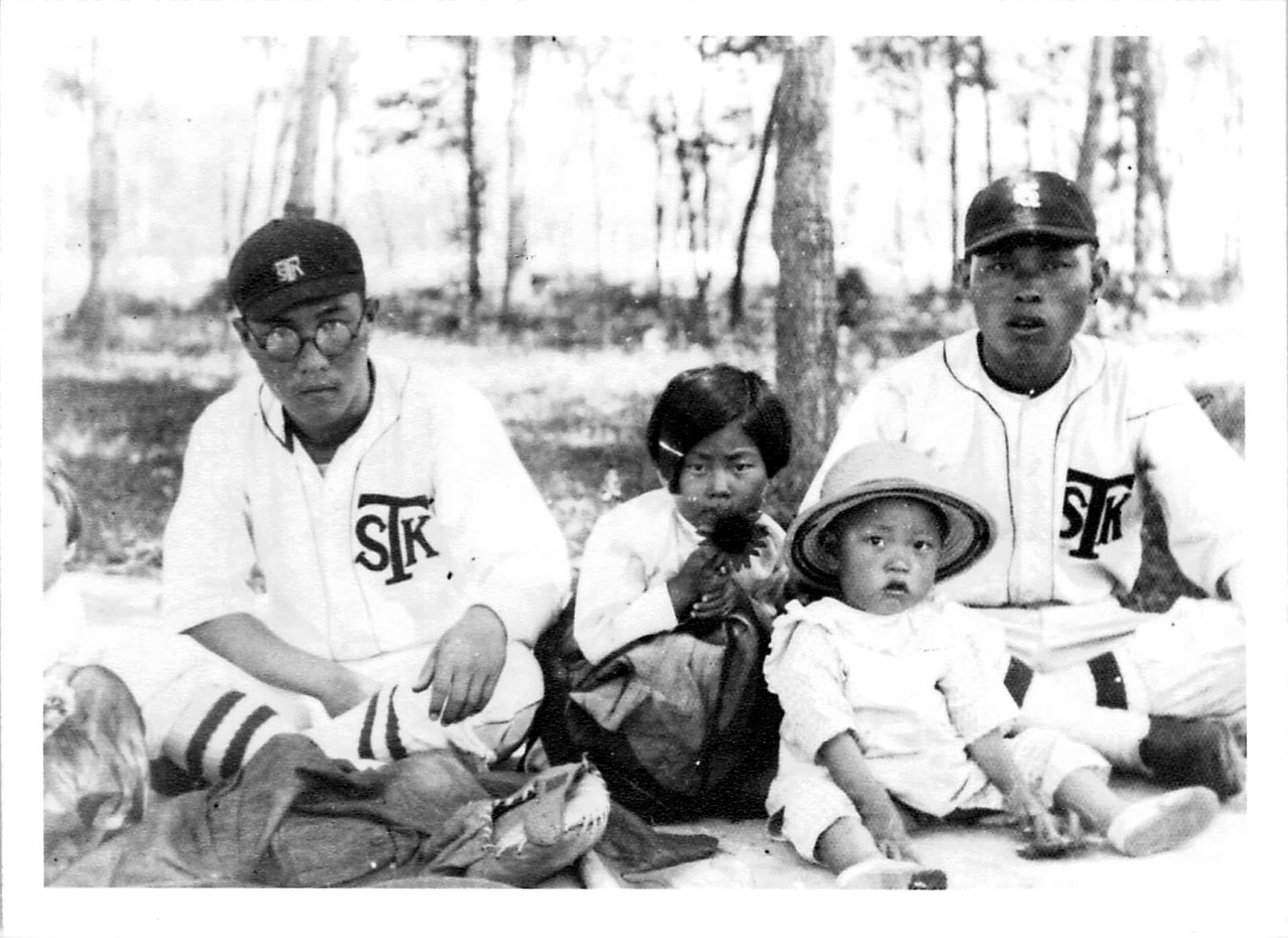

No Kum Sok, age 3, wearsing a pith helmet, with his father, No Zae Hiub (right), an all-star pitcher for his company’s baseball team, in Sinhung, Korea, in 1935.

Plenty of American families have wild stories about how their ancestors came to settle in the United States. But few of them involve someone defecting from an enemy nation in a fighter plane.

Kenneth Rowe is an 83-year-old retired engineer from Daytona Beach, Florida. No Kum Sok is the name he was born with in northern Korea. But going back to 1943, when No was an elementary school student, he went by the Japanese name of Okamura Kyoshi.

“The Japanese forced all the Koreans to change [their names] to Japanese sounding name[s],” Rowe says.

World War II was still raging at that time and the Japanese had ruled Korea for nearly four decades. Japan treated the Korean peninsula and the people who lived there as part of the Japanese empire. Japanese companies dominated the economy. Korean culture was targeted for elimination. The Korean language was banned in Korea. At No’s school, the curriculum was entirely in Japanese.

But there was an upside for No and his family. His father made a good living working for a Japanese conglomerate in Korea, so No had a privileged childhood. He ate well. He had a nice tricycle. He could also read and write Japanese fluently.

“In plain fact, I became 100 percent Japanese,” No says. Before the war ended, however, he learned there were limits to his family’s fealty to Japan.

“You want to dive into an American warship?” No’s father shouted at him. “Are you crazy?”

That is when No Kum Sok lost faith in Japan. He came to understand that the US would win the war. And he learned something else from his father. No became fascinated with the idea of living the good life in the United States. He says he became the most pro-American kid in high school. But openly expressing support for the US soon became dangerous.

After the war, the Soviet Union installed a young Kim Il Sung at the helm of the emerging nation of North Korea. Kim had earned a name for himself as an anti-Japanese insurgent leader operating in northeast China. In August 1945, just as the Japanese were offering their unconditional surrender, US officials hastily chopped the Korean peninsula in half along the 38th parallel. The Soviets took charge in the North and the US would set up a new government in South Korea.

The first time No Kum Sok laid eyes on Kim Il Sung was in early 1948. No was a 16-year-old high school student. The man who would become the Great Leader was guarded by soldiers with Soviet-made submachine guns. Kim stood on top of a hill of fertilizer and gave a rousing speech, No says.

“Our workers are now mass-producing fertilizer essential for the peasants,” Kim told the crowd.

No was mightily impressed with Kim as a public speaker. But No says he had already come to despise the Communists — and Kim Il Sung — by that time.

With a clear sense of which direction the political winds were blowing, No made up his mind to become a “No. 1 Communist” in the eyes of the people around him.

“In order to get ahead, I [had] to show … my faithfulness to Kim Il Sung, even though I was not a Communist. Of course, inside, I was the other way around. I hated [it],” No says.

It was all a big lie for a young man who still dreamed about moving to the US some day. But the lie also saved his life. No stepped up his Communist zealot act after he entered the North Korean military. He cultivated the appearance of extreme devotion to Kim Il Sung and his ideology throughout the Korean War by starting a pro-Communist newspaper, shouting slogans with gusto and denouncing his peers for their lack of nationalist enthusiasm.

No volunteered for the North Korean air force and trained to become a fighter pilot. He flew dozens of combat missions in a Soviet-made MiG-15 fighter jet against better-trained, better-equipped American fighter pilots. But he says he held back from dogfights with the Americans, not wanting to risk being killed or having to shoot down a US pilot.

No Kum Sok saw his chance to escape in September 1953, not long after a ceasefire agreement brought an end to the Korean War. He did it during a training mission on a clear Monday morning by flying his MiG-15 right out of North Korea, across the 38th parallel, and landing it safely at a busy American military base outside of Seoul. With American fighters and anti-aircraft guns as his biggest worries, No figured he had a 20 percent of success. But the US military never even saw him coming.

"The luckiest thing was that the US radar was shutdown on that morning, when I got there. They had maintenance work," he says.

No touched down unscathed, though he narrowly missed a head-on collision with an American fighter jet landing on the same runway from the opposite direction. He got out of his MiG and tore up a picture of Kim Il Sung he had kept in the cockpit. American military personnel surrounded him. And instead of arresting No, they shook his hand and started taking pictures.

The personal stories of No Kum Sok and Kim Il Sung are weaved together in a new book called “The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot,” by Blaine Harden. The author says the project started in 2012, when Rowe called him up out of the blue.

The personal stories of No Kum Sok and Kim Il Sung are weaved together in a new book called “The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot,” by Blaine Harden. The author says the project started in 2012, when Rowe called him up out of the blue.

“He telephoned me and he introduced himself as Ken Rowe. [He] said that his name used to be No Kum Sok. He asked me if I knew who he was and I had no idea,” says Harden, who had written a best-seller about another North Korean defector called, “Escape from Camp 14.”

Harden says Rowe suggested that he read up about his own story of defecting from North Korea. “So, I did. I read some stuff over a few days and called him back, and asked him if he would participate in a book about his escape and about the rise of the man who invented North Korea,” Harden says.

Coming from a country that rewards mindless supplication to the Kim regime, No Kum Sok stands out as a wily risk taker. In a scene described in Harden’s book, No once contemplated taking out his military issued pistol and shooting Kim Il Sung dead during a visit to an air base in North Korea. But No decided against doing something that would get himself killed, sticking with his plan to defect.

US intelligence officials were delighted to get hold of a MiG-15 in 1953, as this old film gets across in extensive technical detail. And as a bonus, the Americans had a smart, cooperative and experienced North Korean fighter pilot to explain how the jet worked. “It was one of the biggest moments of the Cold War. A pilot with this aircraft had never defected before,” Harden says.

No Kum Sok laid out the entire backstory of the North Korean air war for American officials, Harden says. “They interrogated him with incredible energy, about 6 hours a day, 5 days a week, for nearly 7 months,” he says.

The US government files on those interrogation sessions were declassified right before Rowe contacted Harden in 2012. Harden says the documents, along with an autobiography written by Rowe in the 1990s called “A MiG-15 to Freedom,” were critical in verifying the details of No Kum Sok’s story.

In the end, Rowe was able to go to college, get a job as an aeronautical engineer and invest his reward money wisely. He brought his mother to the US from Korea in 1957. She helped him find a spouse and Rowe raised a family in America. He says he never second-guessed his decision to escape from North Korea and make a new life for himself in the US.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?