Louisiana’s much-needed plan to save its wetlands is short almost $50 billion

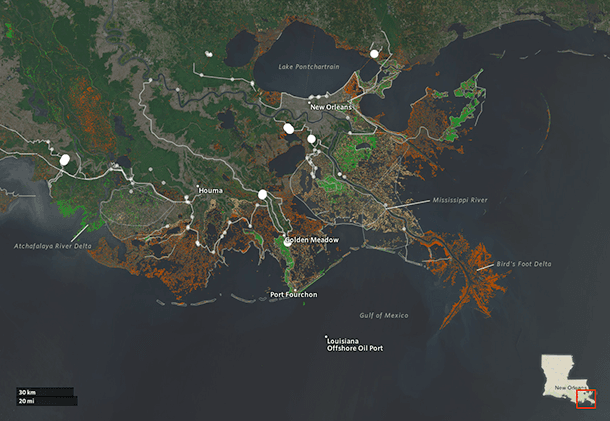

Louisiana’s Master Plan for the Coast includes projects like marsh creation, sediment diversion, structural and shoreline protection, hydrologic restoration and oyster reef restoration. If implemented on time, it could restore and save some crucial wetland areas (in yellow and green).

The state of Louisiana is in trouble: The Mississippi River Delta is disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico at the rate of 16 square miles a year — some of the fastest land loss on the planet.

These bayou lands are crucial to the nation's fisheries, as well as to regional oil and gas supplies — even as activity by the energy industry in the region is helping to destroy its own infrastructure.

So industry and government have created an unprecedented plan to save and rebuild these wetlands over the next 50 years, at an estimated cost of $50 billion dollars.

“What they're trying to do here has never been done before,” says Bob Marshall, who co-authored an analysis of the plan called "Losing Ground, Part II: Louisiana’s Moon Shot" with investigative journalism site ProPublica “They’re trying to rebuild some of the wetlands that have been lost and then maintain them against [many] unknown variables. So in a very real sense, it is as ambitious as going to the moon for the first time.”

The heart of the project is “marsh re-creation.” Engineers dredge sediment out of the Mississippi River and pump it into some of the sinking areas in an attempt to mimic the way the river built up the region over centuries. The state hopes to do this in areas totaling 33,000 acres.

The project also includes shoreline stabilization, rebuilding oyster reefs to help protect shorelines from heavy waves and correcting the structural deficiencies of levies along the river.

Most of these projects are planned along a 50- to 60-mile stretch of river starting in New Orleans and going southward. “The last 30 or 40 miles of the river delta is just being given up because it's sinking at such a fast rate," Marshall says. "There’s no hope of really saving those areas."

According to computer projections, if everything works according to plan and is implemented on time, Louisiana could actually be gaining more land than it’s losing by 2060. “The problem is, they don’t have $50 billion dollars,” Marshall notes drily.

In 2007, Congress authorized about 27 projects that are part of the overall plan, but they haven't funded any of them. Marshall says lawmakers are waiting to see how much money the state will get from BP as a result of the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

“The state recently said they could maybe realize $4 or $5 billion dollars,” he says. “If they don't find other revenue sources, they figure they'll probably run up against a financial wall in about 10 years. … They’re hoping that Congress will look at this and say this is an investment worth making, because it pays for itself in its economic benefits to the country.”

But so far, the only help Louisiana has gotten from the federal government is "in the form of rebuilding the levies that they didn't build properly around New Orleans, and that collapsed during Katrina,” Marshall says.

Ironically, the state's congressional delegation is among the most aggressive in opposing climate legislation. Yet according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the delta region of Louisiana is more endangered by sea level rise — which the scientific consensus says is a direct result of climate change — than anywhere else in the country.

“So other states are saying, ‘Wait a minute, you're like someone with lung cancer who wants us to help pay for the chemo but doesn't want to quit smoking,’” Marshall says. “But down the road, if this isn't the number one issue for the politicians in the state, I think there will be another tremendous crisis here. There will be a storm eventually that will flood a bunch of these communities, knock out refineries, expose or break a lot of these pipelines — and then the nation will have to deal with that.”

Unfortunately, Marshall says, “that’s pretty much historically the way the country deals with these things. We kind of move forward by crisis rather than doing proactive things.”

Marshall says a crisis point is fast approaching. “If they don't get this done in 50 to 60 years, they can't get it done. [The result] will be a massive environmental evacuation from this part of the state to the north, finding homes for people and industries.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?