To see the changes Edward Snowden wrought, just look at your smartphone

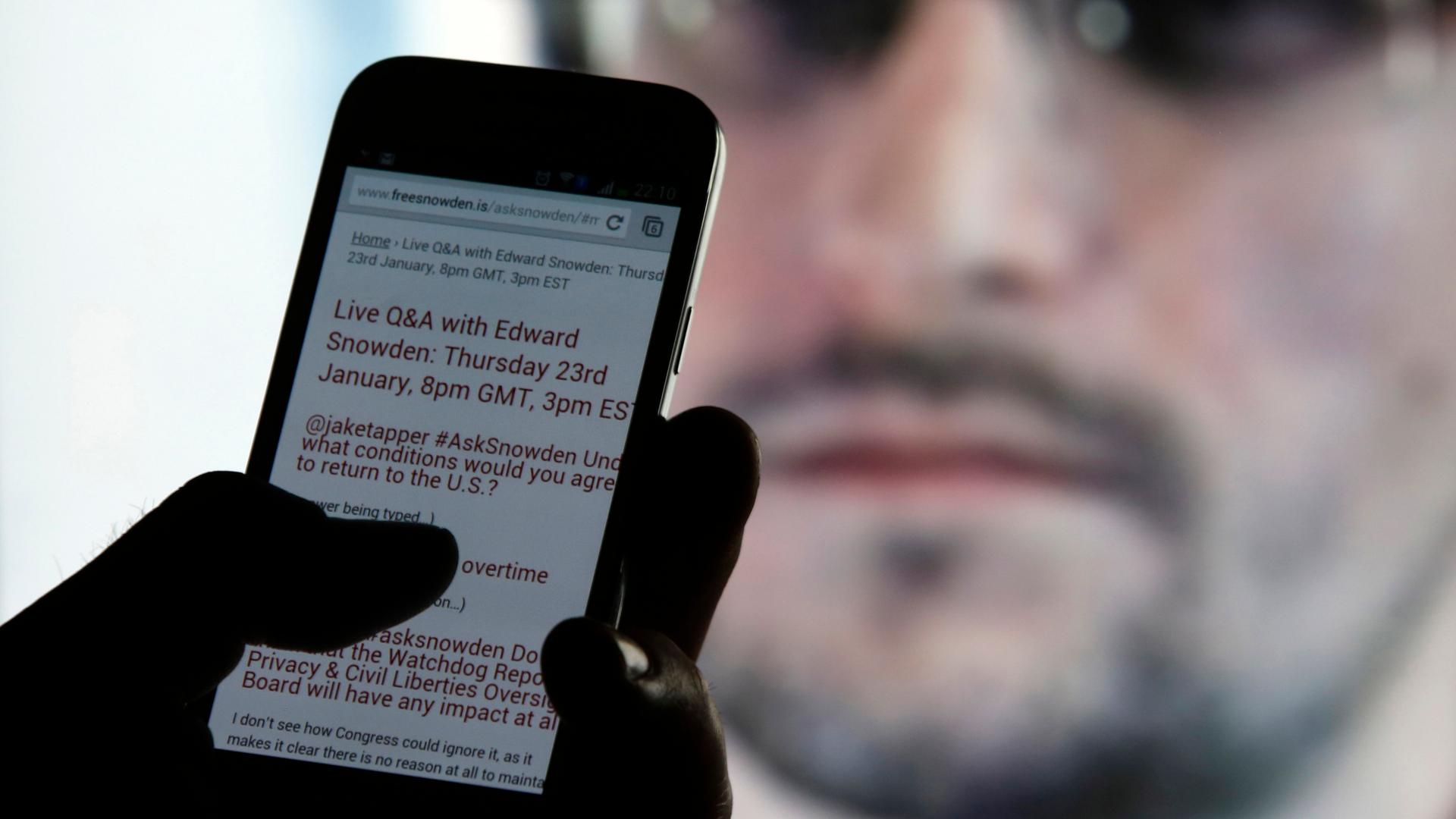

A man uses his phone to read updates about former American NSA contractor Edward Snowden answering users' questions on Twitter.

After Edward Snowden leaked information about a wide range of government surveillance programs, many people expected a major legal shift in the world of Internet security. But calls for stricter laws may be missing the point.

“Most people want to see statutory change or policy change as evidence that there’s been some real impact from the Snowden leaks," explains Bobby Chesney, a law professor at the University of Texas. "But, in a way, I think that’s turning out to be the wrong place to look,”

Chesney says the real change is in the private sector — specifically, in the changing relationship between the private telecommunications and internet companies and the US government.

“Thanks to the way that the Snowden story has catalysed interest in privacy, [there's] pressure on companies to be more privacy-protective," he says. "There’s something of a sea change underway.”

Just look at your smartphone: Apple and Google have made encryption a default setting on their devices to ensure the privacy of the user — so much so that even the providers, let alone the government, can't access the device’s information.

“The default encryption model, in theory, makes it hard — if not impossible — for the company themselves to unlock data on, say, a suspect’s or target’s cell phone or iPad,” Chesney says.

That has caused an obvious rift between intelligence agencies and private technology companies. “The claim is it’s not that [the FBI] is seeking new authorities, but that their existing authorities don’t mean what they used to because of this technological change," Chesney explains.

The new Congress will also have to tackle the issue of whether government agencies can continue bulk metadata collection — the practice that allows them to vacuum up information about phone calls regardless of whether they've been identified with crimes or terrorism.

“All they’re really talking about is whether the government will hold that haystack of data itself, or if, instead, it will all be held in a disaggregated way in the hands of all the telecommunication companies that are involved,” Chesney says.

With legal change on the horizon and private change well underway, the legacy of Snowden is hard to ignore — especially for Chesney. In his basic course on national security law, he used to cover internet security in just four or five days. Last year, he says, “we had to more than double that, and it wasn’t nearly enough.”

Chesney adds that Snowden is nothing if not divisive: “Personally, I think that it’s like a lot of issues, where there are some elements cutting one way, some elements cutting strongly the other way. And that makes him a very human figure, if nothing else.”