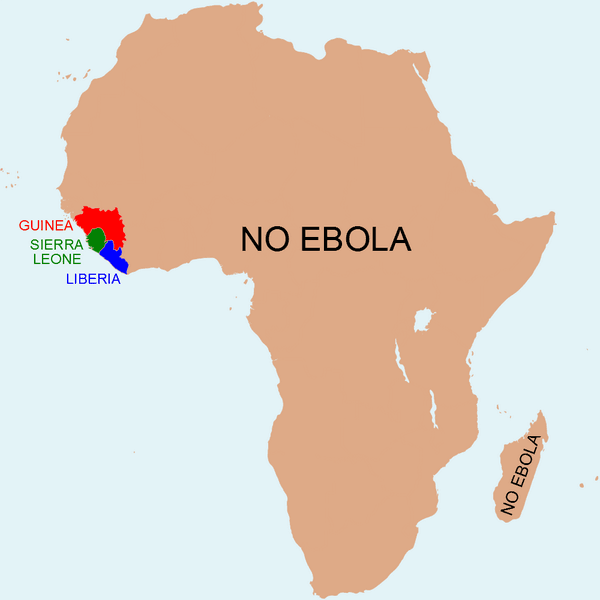

A satirical map created by Anthony England to show people around the world how little of Africa has been affected by the Ebola outbreak.

An unemployed chemist recently found himself yelling at inanimate objects in his home.

"I've shouted at my computer quite a lot recently and at the television, too," admits Anthony England. "I've heard so much nonsense being spoken about Ebola."

With time on his hands, a background in science and considerable experience in West Africa, England has been spending a lot of time following news about the Ebola outbreak, especially on social media.

That's how he came across a tweet from a guy in Kentucky about a teacher in the state who was forced to resign from her job after volunteering in Kenya. "So a teacher from Kentucky goes to Kenya, ends up resigning her job because staff, students, parents think she was in the Ebola zone. She wasn't in the Ebola zone. She was nowhere near the Ebola zone!" he says with disbelief. "She was something like 3,000 miles away!"

So England decided to make a map to show that "Africa" isn't a way to think about the disease. He drew the outline of the African continent, but showed the borders of only the three small countries currently affected by the Ebola outbreak: Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. He labeled the rest of the map "No Ebola."

"I guess what I'm saying is if you want to talk about Ebola in Africa, talk about these three countries," says England. "Think only about Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Focus on them and try and get Ebola stopped in those three countries, because that's how it stops for the entire planet. It's that simple."

The map went viral in a big way, getting thousands of retweets and attention from media across the world. His Twitter followers, many of them from Africa, are delighted with the map, and some have translated it into other languages or added additional information.

England adapted his own map to respond to one complaint: that Ebola had indeed reached beyond Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, if only fleetingly. So he updated it with a key, acknowledging that the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali and Nigeria had all seen cases of Ebola.

"It's fair enough to mention Congo. There is still officially an outbreak going on there that hasn't been certified as finished. The same goes for Mali," he concedes. "There could be an outbreak coming soon, but currently there are no cases. But so many other countries just shouldn't even be mentioned."

He points out that tweets like the one from Kentucky can be seriously damaging. "The fact that Kenya feels that its tourism industry is being affected is just insane, he says. "It's just silly … and it's built on absolute misinformation and ignorance about the entire situation. And that's unacceptable because in the long run that leads to misplaced fears, bad policies."

England's passion for accurate information about Ebola is partly personal. One of his first jobs after leaving scientific research 10 years ago was hosting conferences in West Africa, "trying to get scientists from the developed world better connected with the developing world and its scientists," he explains.

"Rather than having big shiny conferences in Las Vegas, New York, London or Amsterdam," he says, his company tried "getting scientists of the developed world to go and have fun at a conference in Africa to see that it, in itself, can be great fun."

As for his hastily-made Ebola map, he's thrilled that it's making a point. "It really seems like people are getting to grips with my simple little map. It's just pointing out the obvious." And he recently found another way to spread the word: