Global wildlife populations have fallen by half — a stat that says it all

The total number of wild animals in the world has dropped by more than half in just 44 years, according to the World Wildlife Fund’s new Living Planet Report. The report compiled data for more than 10,000 vertebrate species, along with trends in humanity’s global footprint and Earth’s “biocapacity.”

Every now and then, a single statistic tells you more about the world we live in than a firehose of news ever could. Here’s one of them: Since 1970, the Earth has lost more than half its wildlife.

Let’s say that again: There are roughly half as many wild creatures, or at least vertebrates, on our planet today as there were when many of us were kids. That shocking stat comes from a new report from the World Wildlife Fund and partner organizations, including the Zoological Society of London.

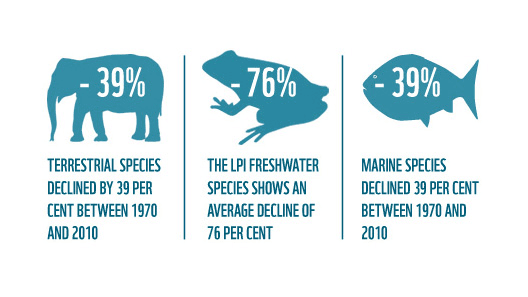

The WWF’s latest Living Planet Report compared the latest population data for roughly 10,000 vertebrate species — mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish — with data from 44 years ago, when the organization began this series of reports. It found huge declines across the board, but especially in fresh water systems and in the tropics. The decline hit a jaw-dropping 83 percent in Latin America.

"It’s tragic," says Keya Chatterjee, WWF's director of Renewable Energy and Footprint Outreach. Chatterjee says the decline includes iconic creatures like African lions, Asian forest elephants, sharks, rays, leatherback turtles, dolphins and seals.

But the report makes clear that it’s about way more than documenting and grieving the loss of specific animals. “These are the living forms that constitute the fabric of the ecosystems which sustain life on Earth — and the barometer of what we are doing to our own planet,” writes Marco Lambertini, WWF International’s director general, in the report’s foreward. “We ignore their decline at our peril.”

The report also makes it clear that humans are the cause of that decline. Along with the species numbers, the report measures two other directly related factors: the human ecological footprint — a measure of the consumption of goods and greenhouse gases we produce — and the earth’s "biocapacity," or its ability to produce vital goods like food and fresh water, and to continue doing life-sustaining tasks like regulating the composition of the atmosphere.

Together, Chatterjee says, these datasets give us "(a) full picture of what’s happening on the planet." And she says that picture shows that human demands on the Earth are outstripping its ability to provide those other goods and services by half. "Our demands on the planet are unsustainable right now," she says.

The report identifies several main overall causes of the decline in wildlife, including habitat loss and degradation, exploitation through hunting and fishing, and climate change.

Not surprisingly, these trends emerged as the human population has nearly doubled to more than 7 billion people since that same 1970 benchmark. But Chatterjee says most of the responsibility for the surging stress on the planet's resources and ecosystems comes from its richer nations.

As an example, Chatterjee cites an issues she thinks people rarely consider: food waste. "In this country … we actually throw away a third to a half of the food that we purchase," she says. "What that means is that food that is grown elsewhere, [often] where we’ve had massive deforestation in order to grow that food — it’s getting exported here not even for our own consumption but for us to throw it away.”

Chatterjee draws a direct connection between the stark decline in wildlife and personal actions like food waste. “If we continue to make the choices that we are making,” she says, “this is what will continue to occur.”

But she adds an important caveat: "There’s nothing inevitable about these trends.” Changing course will require changes massive and minor, but they are possible.

Chatterjee says in thinking about the loss of wildlife and other massive planetary challenges, it’s also important to stay focused on why we care. “When I think about why we need to tackle these issues, I think about my son,” she says. He’s “my source of inspiration … [And] it’s a core part of my responsibility as a parent to tackle this on every front.”

Having a child has shifted the terms of the danger, Chatterjee says: “Before having a child, it was easy for me to read about what we call in the climate community ‘mid-century projections.’ But now all I can think of is that that’s when my son is 40. And that’s a result of the way we’re using planetary resources. And that has to change."