Here’s why the US and Europe are so far apart on climate policy

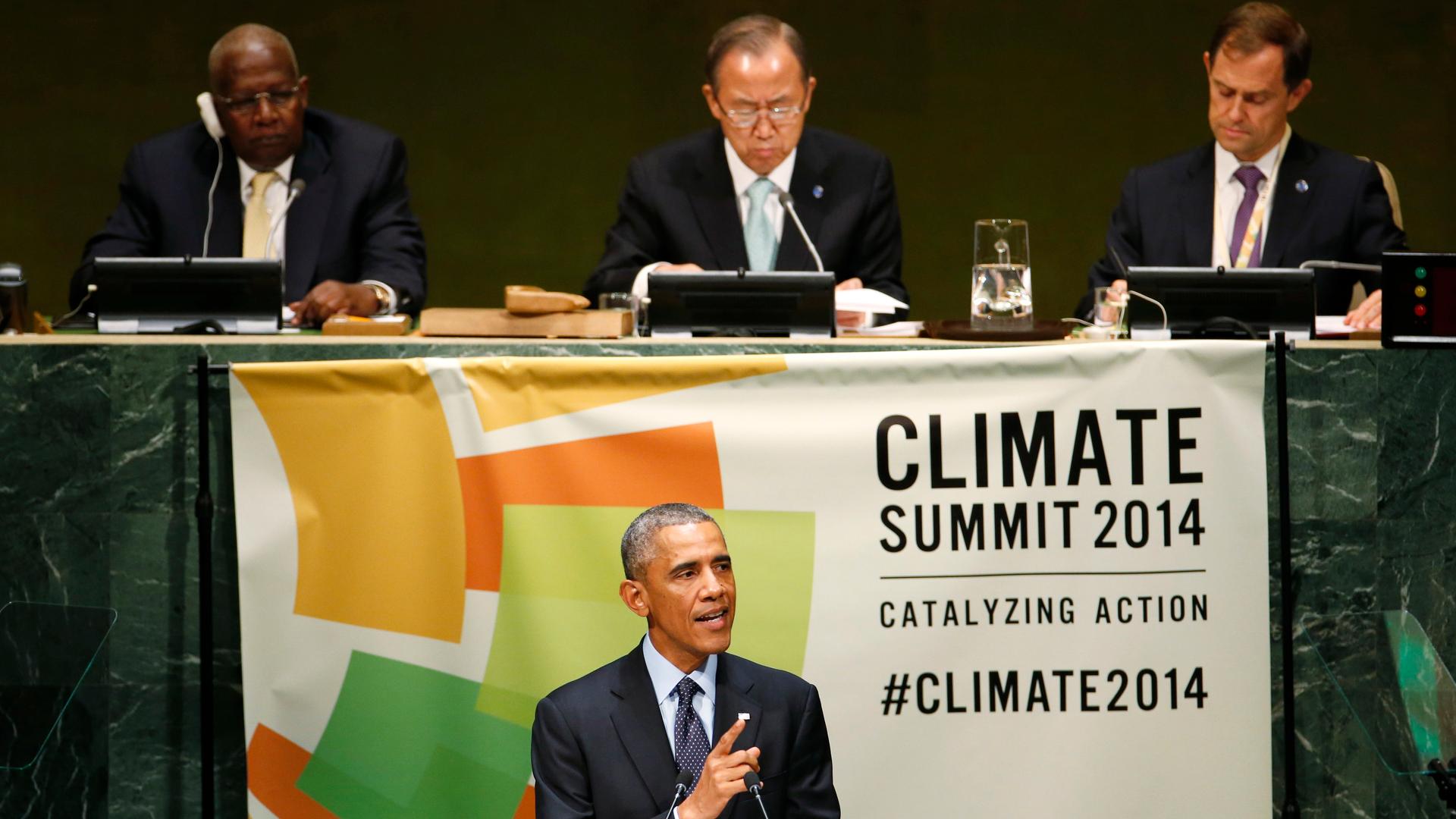

President Barack Obama addresses the Climate Summit at UN headquarters in New York on September 23, 2014. Obama touted American commitments to cut greenhouse pollution, but international agreements have been undercut by sharp internal divisions in the US over climate policy.

World leaders converged at the United Nations in New York on Tuesday, declaring their intent to step up efforts against climate change. But if the gathering was meant to demonstrate their collective resolve, it also highlighted the big gulfs between crucial global players.

Some of the biggest rifts are between the United States and big developing countries like China and India, but there's also a wide gap on climate policy between the US and its closer friends in Europe.

The European Union, for instance, has pledged to cut greenhouse gas pollution to 60 percent of the 1990 emissions level by 2030. The US has pledged a much smaller goal: Reducing its 2005 emissions level by 17 percent over the next six years. That's much smaller cut from a much higher base.

And while European countries have largely embraced international cooperation and the idea of a global treaty on climate, that’s been a nonstarter here in the US.

“[In] the US, in order to make international law, approval of Congress and the Senate are needed in advance,” says Clarisse Kehler Siebert, a Canadian international lawyer and researcher at the Stockholm Environment Institute. That “makes it very difficult to come to an international gathering and make promises.”

But in the EU, government structures give leaders more leeway to enter into international agreements “and then to go home and figure out just how those goals and targets are going to be met," she says.

“Essentially that's what we've seen in international lawmaking in the climate context," Siebert says. "And the result is that the EU can come out looking proactive and the US can come out looking like the slow-moving bad guy.”

Of course, there are different fundamental values underlying these political differences. “There's a different spirit that drives public policy, there are different interests,” Siebert says, including the power of corporate interests and the role of money in politics. “In Europe, it's not private entities that are funding political campaigns.”

Another big difference is the ongoing debate in the US over basic climate science. In Europe, Siebert says, the debate over whether or not climate change is very much a fringe conversation.

“The role of climate science, and the space and voice of climate skepticism, is quite different” in Europe, she says. “To my knowledge, for example, there aren't any big media outlets for climate skepticism.”

Overall, Siebert says, there’s a very different “culture of cooperation and meeting a common challenge that drives European politics, but isn't present in the US”

Still, she says, the picture on climate action in the US has some important bright spots. “I think there's something about the lack of progress at the national level in the US that has driven really interesting, creative, entrepreneurial action at sub-national levels,” Siebert says, including innovations among states and cities that may not be comparable to anything in Europe.

She says those efforts, even if small, should be celebrated: "Of course there’s the challenge of adding all of those individual actions up and seeing if it’s enough. But it’s certainly a good starting point.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?