Technology is allowing us to watch the world’s forest disappear in real time, and hopefully halt it

An Indonesian worker pushes a cart of palm oil fruits. Indonesia and Malaysia account for about 85 percent of the global output of palm oil, used in foods ranging from margarines and biscuits to instant noodles. April 16, 2014.

Here’s a story we’ve been hearing for decades — the world’s rainforests are rapidly disappearing.

“We’re continuing to lose forests at a stunning rate,” said Nigel Sizer, director of the forests program at the World Resources Institute in Washington. “At the rate of 50 soccer fields a minute, every minute, every day, every year.”

Sizer can rattle off these figures because he’s been watching deforestation happen in near real time.

From his laptop, Sizer zoomed in on some Indonesian rainforests, critical habitat to some of the world’s greatest biodiversity, including threatened species like orangutans and the Sumatran tiger and elephant. Many farmers there are clearing trees to plant palm illegally — a key ingredient in many processed foods — in dense jungles far from the watchful eyes of authority.

Worldwide, healthy forests are also a big piece of the puzzle for fighting climate change — roughly 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from forest loss.

“We can zoom right in here, and you can see clearing down to the scale of a small plantation, and zoom in further, you’re looking at the crowns of individual trees. So we’ve gone from the entire world, right down to individual trees seamlessly in one system,” Sizer said.

OK, I know what you’re thinking: big deal. I can use Google Earth to zoom in on my home. True. And Sizer is using Google technology here. But he’s also using NASA’s archive of satellite imagery going back more than a decade. Scientists at the World Resources Institute, Google, and the University of Maryland have developed algorithms to compare historical and current images to detect exactly what’s been cut, where.

“It’s thousands and thousands of hours of computing time to generate these outputs. And then we take that, which is actually a very complex set of data, and we display it in a simple and easy to use way on Global Forest Watch,” Sizer said.

“It’s thousands and thousands of hours of computing time to generate these outputs. And then we take that, which is actually a very complex set of data, and we display it in a simple and easy to use way on Global Forest Watch,” Sizer said.

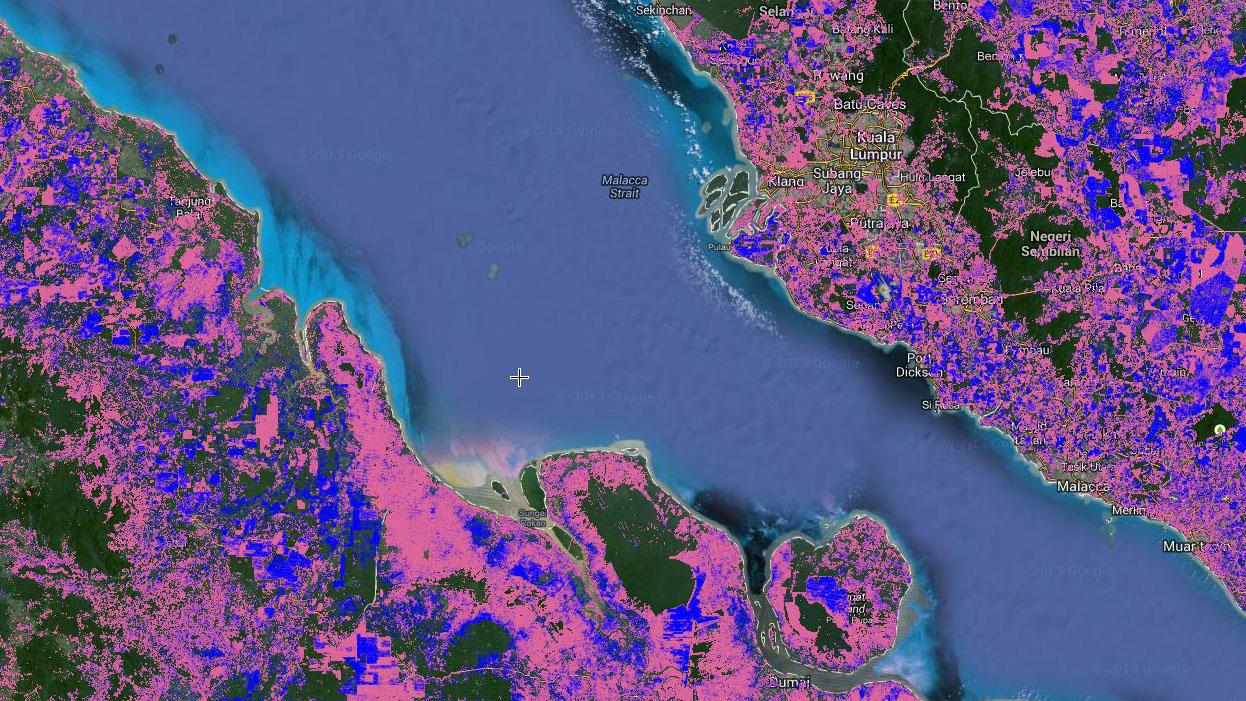

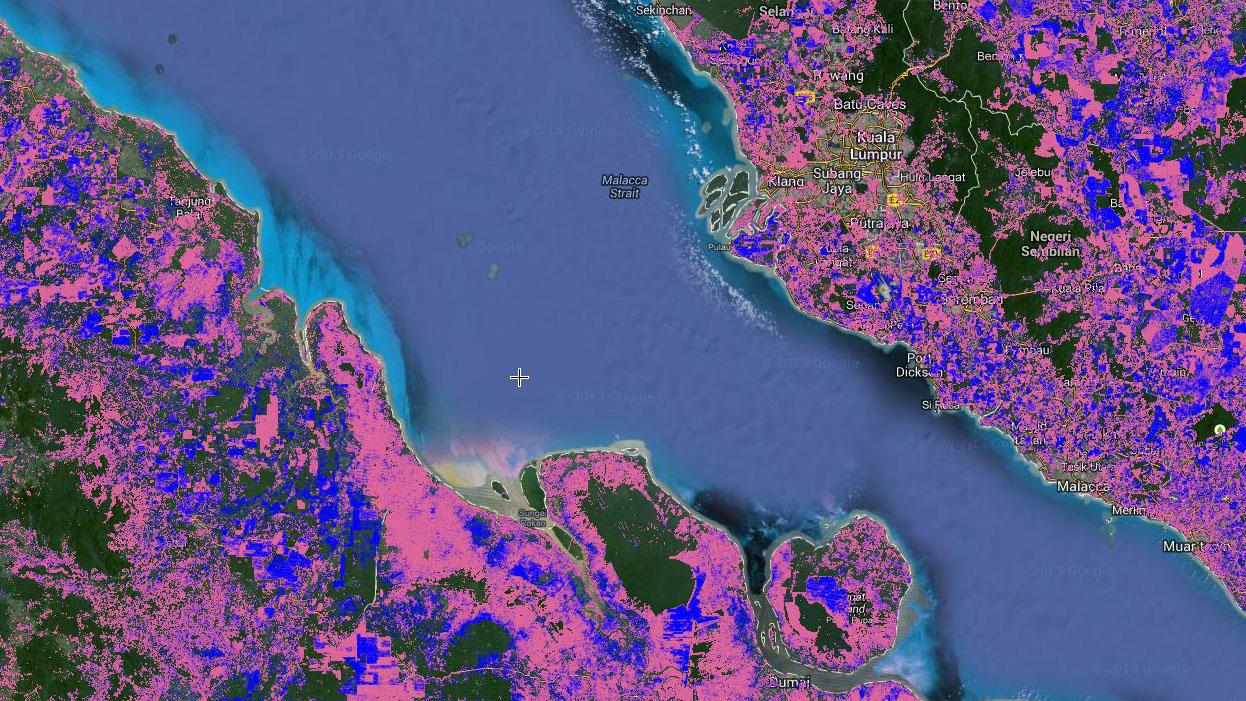

Global Forest Watch is the name of the website anybody can check out. Pink pixels on the map mean forest has been cleared. Blue means new trees have been planted. That’s how the maps work. Here’s what they can do — publicly shame multinationals from buying palm oil from plantations on illegally cut or burned tropical forest.

“So a company that might be buying that palm oil is then in the public spotlight, absolutely,” said Sizer. “It’s a powerful tool for holding companies accountable and ensuring they live up to their commitments.”

Nestlé understands public shaming. Four years ago, Greenpeace launched a media campaign against Nestlé for buying palm oil from illicit sources. Rather than fight, Nestlé said, you’re right. The Swiss company committed to only buying sustainably-harvested products. But that was the easy part, explains Nestlé’s Duncan Pollard, who works on sustainability and stakeholder engagement.

“We have long complex supply chains, and we’ve traditionally bought from what we call first-tier suppliers,” Pollard said. “Behind that is a long, complicated supply chain, perhaps with second, third, fourth or more suppliers below.”

It can be pretty impenetrable — sometimes on purpose. The less you know, the less you’re responsible for. Even for companies that want to decipher their supply chain, like Nestlé, it’s been a struggle. But now, they too are using the new online maps.

“Until these maps came along, it really wasn’t possible for us to know where exactly is deforestation happening. Governments, of course would publish data, but they’d publish national level data,” Pollard said.

Environmentalists, like Michael Jenkins, president of the NGO Forest Trends in Washington, applaud the new mapping technology and vanguard companies like Nestlé that are using it. But Jenkins adds a dose of realism.

“It’s great to say here is illegal logging happening, but the real issue is what are we going to do about it? Why are we logging illegally — because the forests that we’re logging are not as valuable as the oil palm that is so lucrative,” Jenkins said.

Ultimately, Jenkins said, we need to find ways to put a real value on the forest themselves. But that’s a more complex issue.

Meanwhile, the new satellite maps add a layer of enforcement, and there are more high-tech tools in the pipeline.

“You can take samples of wood from, say, a table on sale in IKEA and analyze DNA in that table and know exactly where it came from,” Sizer said.

He added, he just hopes more multinational companies will be willing to use these new cutting edge tools to help preserve the world’s forests.

Here’s a story we’ve been hearing for decades — the world’s rainforests are rapidly disappearing.

“We’re continuing to lose forests at a stunning rate,” said Nigel Sizer, director of the forests program at the World Resources Institute in Washington. “At the rate of 50 soccer fields a minute, every minute, every day, every year.”

Sizer can rattle off these figures because he’s been watching deforestation happen in near real time.

From his laptop, Sizer zoomed in on some Indonesian rainforests, critical habitat to some of the world’s greatest biodiversity, including threatened species like orangutans and the Sumatran tiger and elephant. Many farmers there are clearing trees to plant palm illegally — a key ingredient in many processed foods — in dense jungles far from the watchful eyes of authority.

Worldwide, healthy forests are also a big piece of the puzzle for fighting climate change — roughly 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from forest loss.

“We can zoom right in here, and you can see clearing down to the scale of a small plantation, and zoom in further, you’re looking at the crowns of individual trees. So we’ve gone from the entire world, right down to individual trees seamlessly in one system,” Sizer said.

OK, I know what you’re thinking: big deal. I can use Google Earth to zoom in on my home. True. And Sizer is using Google technology here. But he’s also using NASA’s archive of satellite imagery going back more than a decade. Scientists at the World Resources Institute, Google, and the University of Maryland have developed algorithms to compare historical and current images to detect exactly what’s been cut, where.

“It’s thousands and thousands of hours of computing time to generate these outputs. And then we take that, which is actually a very complex set of data, and we display it in a simple and easy to use way on Global Forest Watch,” Sizer said.

“It’s thousands and thousands of hours of computing time to generate these outputs. And then we take that, which is actually a very complex set of data, and we display it in a simple and easy to use way on Global Forest Watch,” Sizer said.

Global Forest Watch is the name of the website anybody can check out. Pink pixels on the map mean forest has been cleared. Blue means new trees have been planted. That’s how the maps work. Here’s what they can do — publicly shame multinationals from buying palm oil from plantations on illegally cut or burned tropical forest.

“So a company that might be buying that palm oil is then in the public spotlight, absolutely,” said Sizer. “It’s a powerful tool for holding companies accountable and ensuring they live up to their commitments.”

Nestlé understands public shaming. Four years ago, Greenpeace launched a media campaign against Nestlé for buying palm oil from illicit sources. Rather than fight, Nestlé said, you’re right. The Swiss company committed to only buying sustainably-harvested products. But that was the easy part, explains Nestlé’s Duncan Pollard, who works on sustainability and stakeholder engagement.

“We have long complex supply chains, and we’ve traditionally bought from what we call first-tier suppliers,” Pollard said. “Behind that is a long, complicated supply chain, perhaps with second, third, fourth or more suppliers below.”

It can be pretty impenetrable — sometimes on purpose. The less you know, the less you’re responsible for. Even for companies that want to decipher their supply chain, like Nestlé, it’s been a struggle. But now, they too are using the new online maps.

“Until these maps came along, it really wasn’t possible for us to know where exactly is deforestation happening. Governments, of course would publish data, but they’d publish national level data,” Pollard said.

Environmentalists, like Michael Jenkins, president of the NGO Forest Trends in Washington, applaud the new mapping technology and vanguard companies like Nestlé that are using it. But Jenkins adds a dose of realism.

“It’s great to say here is illegal logging happening, but the real issue is what are we going to do about it? Why are we logging illegally — because the forests that we’re logging are not as valuable as the oil palm that is so lucrative,” Jenkins said.

Ultimately, Jenkins said, we need to find ways to put a real value on the forest themselves. But that’s a more complex issue.

Meanwhile, the new satellite maps add a layer of enforcement, and there are more high-tech tools in the pipeline.

“You can take samples of wood from, say, a table on sale in IKEA and analyze DNA in that table and know exactly where it came from,” Sizer said.

He added, he just hopes more multinational companies will be willing to use these new cutting edge tools to help preserve the world’s forests.