Shakespeare’s fountain of brilliant words: Has it been found?

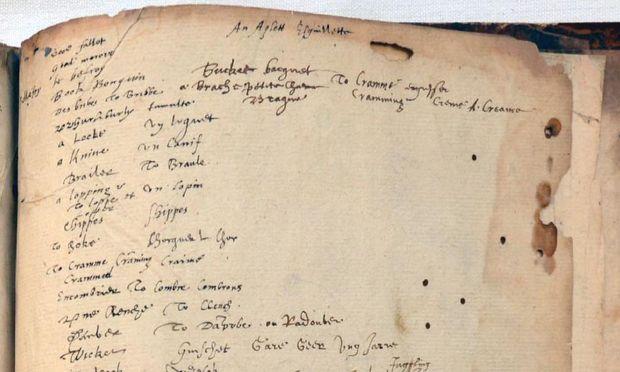

Booksellers claim they have found a dictionary that belonged to William Shakespeare. On this page, they believe he wrote a mixture of French and English words, also used in his plays.

“If you announce to the world that you’ve found Shakespeare's own personal dictionary on eBay, the first problem you’re going to have is nobody's going to believe you.”

True enough.

Nevertheless, two rare-book dealers say they have found Shakespeare's personal copy of John Baret’s 1580 dictionary, Alvearie, which they claim is covered with notes that were written by Shakespeare four centuries ago.

Daniel Wechsler and George Koppelman recently published a book called Shakespeare’s Beehive, detailing their argument, and they have put scans of the dictionary on the web for researchers to examine.

Wechsler and Koppelman paid $4050 dollars for the book, which, if it is proven to have belonged to Shakespeare, seems akin to buying the Holy Grail at a yard sale. But Wechsler says a book like this is not as surprising a discovery as it might seem.

“The thing is,” Wechsler explains, “my office is filled with books from the 16th century. They’re not that easy to sell. Only a small portion of the population is interested in rare books, and this is easily a book that could have just passed its way through time without being studied or noticed.”

Shakespeare’s plays and poems have been linked to Baret’s Alvearie before, but Wechsler says he and Koppelman didn’t suspect this particular copy might have been used by Shakespeare himself.

“Deep in our hearts, I think we felt we were bidding on [just] an annotated edition,” he says. “We didn’t know how many annotations there were. We had no idea there would be thousands of them. When the book arrived, we were shocked at how profusely annotated it was.”

Wechsler describes the annotations as a “real interaction between whoever the owner was and the text.” Only after they began to study it more closely did it occur to them that the dictionary might be Shakespeare’s.

Naturally, their discovery has been greeted with a great deal of skepticism from scholars and academics. This is partly because much of the evidence Wechsler and Koppelman use to make their case is circumstantial.

“One of the things we’re faced with is the idea that people want to look at [the book] and see 'Shakespeare' really quickly,” he says. “But you don't see character names, or lines from a [specific] play. What you do see is an annotator fiddling over and over again with the language, messing around with words, looking for synonyms."

If there is a “smoking gun,” he says, it is the “trailing blank” — a leaf bound in the back of the book that has no printed text on it.

“[The annotator] jotted down all these words in English and in French. The rest of the page seems to clearly indicate, through the word choices, that the annotator was remembering bits from the two parts of Henry the Fourth and the Merry Wives of Windsor. These plays…were written right before Henry the Fifth — the one play where Shakespeare uses a lot of French.”

Wechsler believes the list of words on the “trailing blank” and the translation of English words into French may be the origin of Shakespeare’s famous French lesson scene at the end of Henry the Fifth.

Then there are the suspicious “W’s” and “S’s.”

Throughout the book, Wechsler says, whenever the annotator begins a word with a W or an S, he mimics an unusual script form of the capital letters.

“The first one we noticed was the ‘W.’ So we thought, ‘I wonder if he’s copying any of the other letters.’ Sure enough, we go through the whole thing, and ‘S is the only other letter that he treats in that [same] way.”

Wechsler and Koppelman are fully aware that someone other than Shakespeare could have owned this dictionary, and even been drawn to similar words and phrases.

“[The annotator] could have been any number of people,” Wechsler admits. “But over and over again, we see the annotator moving from one place in the text to another page hundreds of pages removed — and the combination of [words] that he's noting appear in one line and one line only, and that line is [in] Shakespeare.”

Wechsler says he and Koppelman tested their theories using sources like EEBO, Early Elizabethan Books Online, where you can search historical texts for various combinations of Renaissance words and phrases.

Though some Shakespeare scholars have been thoroughly dismissive, if not hostile, The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, which holds the world’s largest collection of Shakespeare-related materials, posted a very respectful post on their blog.

Wechsler says he and Koppelman think the Folger statement is “terrific.”

“A lot of people have thrown [the Folger’s response] back at us. But we said, ‘Hey, wait a second: this is the Folger Shakespeare Library, and they chose their own blog to highlight the book and what we've done — and even to applaud the fact we made it available for everyone to see on our website. So we found the Folger statement to be right on the money.”

Because of its reputation in the scholarly world, the Folger Library would be on a very short list of potential buyers, if they decide Wechsler and Koppelman’s discovery is the real thing. Even now, before any further study is done on the book, Wechsler and Koppelman could easily sell it for many millions of dollars. Wechsler says he and Koppelman have no plans to sell it right now.

“We certainly think that a scholarly process needs to take place,” he says. “And where [the book] ends up is as important to us as anything.”

This story is based on an interview by PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen, where you'll find other coverage of popular culture, design and the arts.