For Miami’s immigrants, some of the cheapest land is the most vulnerable to climate change

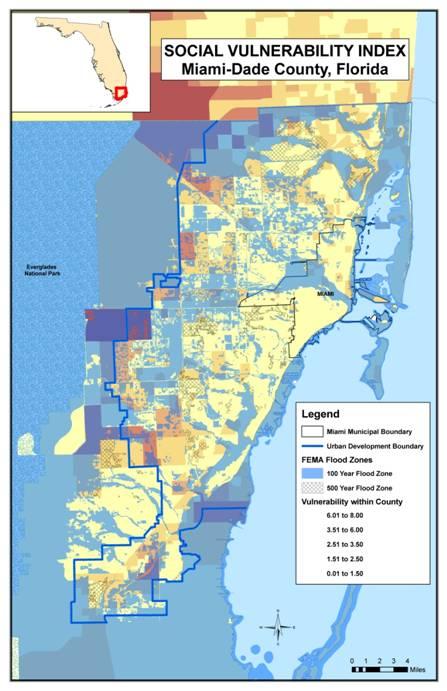

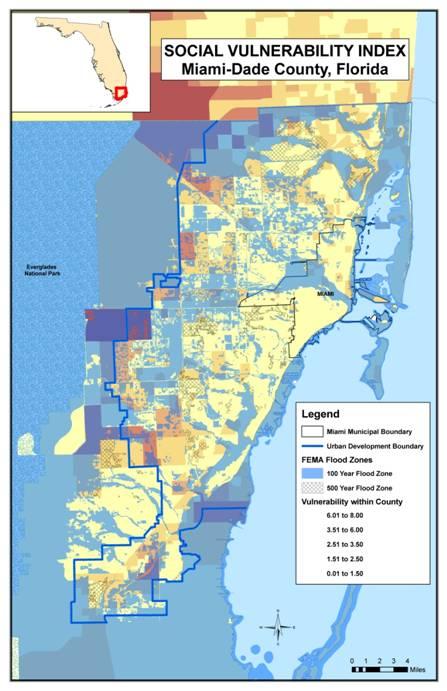

Most of Miami-Dade County and greater South Florida is barely feet above sea level, with new development moving into some of the most flood-prone areas.

Miami is about six feet above sea level and smack up against the ocean. It’s one of the cities most economically vulnerable to sea level rise in the world.

So when there’s talk of sea level rise in Miami, it’s usually focused on the dangers of the Atlantic beginning to engulf some of the most expensive real estate on the planet.

But its not just the rich and famous along Florida’s Gold Coast who have a lot to lose.

Head west in Miami Dade County and you’ll find yourself in booming bedroom communities of mostly Latin immigrants.

Many of these neighborhoods are farther from the sea than Miami, but their elevation is actually lower. And it’s down there, where the land just about melts right into the sea, that you’ll find Celeste De Palma — a woman often in a kayak, and always on a mission.

“You can see how wet the area is,” De Palma says, hunkered low to the water, while leading a tour of the edge of Everglades National Park for the Tropical Audubon Society. “The west side of [Miami-Dade] county is the lowest lying area that we have, and being here sort of puts it into perspective.”

De Palma is a Latin immigrant herself — from Argentina — and an Audubon Society guide and climate activist.

She’s here to show people local wildlife, but also to make clear just how vulnerable the area is to sea level rise.

Many of those bedroom communities are sprouting right on the edge of the park and in other nearby areas, where land is a lot cheaper than it is closer to Miami proper.

De Palma says a lot of her own friends are starting to look at where they can buy a house. “And of course, they want to have the most bang for their buck, and so that tends to be in low-lying areas.”

Those areas are also at high risk of flooding. That’s why De Palma has been working, for years, to slow the migration of newcomers.

Miami Dade County expects nearly 700,000 new residents by 2030, many of whom will be Hispanics attracted by the affordable housing.

That’s where De Palma wants to make a difference. “We have to get the entire population moving,” she says. “Right now … 65% of this county is from Hispanic descent.”

It can be a very tough sell. Climate change can seem like a remote problem, and people tend to have much more immediate concerns.

Which is why De Palma doesn’t stray from her mission, wherever she goes.

In another life, De Palma was a dance instructor — a career she gave up to become an activist. She still fills in occasionally, and brings her message on climate change with her, often in her native Spanish.

After a recent class, with Latin dance music still thumping in the background, De Palma sought help from some of her students in stopping development in some especially vulnerable, low-lying areas. And she found some unexpectedly receptive ears.

Among her enlistees was Katiuska Ferreria, an immigrant from Venezuela who is weary of politics after fleeing strife in her home country.

“Of course, I’ll support her,” Ferreria says, “because I trust what she is trying to do. I didn’t know she was doing this kind of study. I only thought she was in the dancing environment.”

De Palma didn’t plan to become an activist. She wanted to be a dancer. But that changed on a visit to Peru, when she saw the impact of oil drilling on the environment and local indigenous groups.

When she came to the US, she eventually landed a job with the Audubon Society. She’s helped the organization win at least some small victories where the water meets the rising sea in south Florida.

She says it helps that she lives in the area herself, rather than coming in from outside.

“Living in areas where you’re going to be more prone to have floods, you are in a unique position to exert pressure onto your elected officials and help us prepare for sea level rise,” De Palma says.

Among other things, she recently helped keep developers from building a new mall near the Everglades.

On her tour of Florida Bay, thousands of wading birds feed far off in the distance, standing in a foot of water.

It’s not hard to see the birds as a metaphor for what could lie ahead for people here in south Florida, Hispanic and otherwise.

But for De Palma it’s not about standing still, waiting for the inevitable. It’s about taking action.

Miami is about six feet above sea level and smack up against the ocean. It’s one of the cities most economically vulnerable to sea level rise in the world.

So when there’s talk of sea level rise in Miami, it’s usually focused on the dangers of the Atlantic beginning to engulf some of the most expensive real estate on the planet.

But its not just the rich and famous along Florida’s Gold Coast who have a lot to lose.

Head west in Miami Dade County and you’ll find yourself in booming bedroom communities of mostly Latin immigrants.

Many of these neighborhoods are farther from the sea than Miami, but their elevation is actually lower. And it’s down there, where the land just about melts right into the sea, that you’ll find Celeste De Palma — a woman often in a kayak, and always on a mission.

“You can see how wet the area is,” De Palma says, hunkered low to the water, while leading a tour of the edge of Everglades National Park for the Tropical Audubon Society. “The west side of [Miami-Dade] county is the lowest lying area that we have, and being here sort of puts it into perspective.”

De Palma is a Latin immigrant herself — from Argentina — and an Audubon Society guide and climate activist.

She’s here to show people local wildlife, but also to make clear just how vulnerable the area is to sea level rise.

Many of those bedroom communities are sprouting right on the edge of the park and in other nearby areas, where land is a lot cheaper than it is closer to Miami proper.

De Palma says a lot of her own friends are starting to look at where they can buy a house. “And of course, they want to have the most bang for their buck, and so that tends to be in low-lying areas.”

Those areas are also at high risk of flooding. That’s why De Palma has been working, for years, to slow the migration of newcomers.

Miami Dade County expects nearly 700,000 new residents by 2030, many of whom will be Hispanics attracted by the affordable housing.

That’s where De Palma wants to make a difference. “We have to get the entire population moving,” she says. “Right now … 65% of this county is from Hispanic descent.”

It can be a very tough sell. Climate change can seem like a remote problem, and people tend to have much more immediate concerns.

Which is why De Palma doesn’t stray from her mission, wherever she goes.

In another life, De Palma was a dance instructor — a career she gave up to become an activist. She still fills in occasionally, and brings her message on climate change with her, often in her native Spanish.

After a recent class, with Latin dance music still thumping in the background, De Palma sought help from some of her students in stopping development in some especially vulnerable, low-lying areas. And she found some unexpectedly receptive ears.

Among her enlistees was Katiuska Ferreria, an immigrant from Venezuela who is weary of politics after fleeing strife in her home country.

“Of course, I’ll support her,” Ferreria says, “because I trust what she is trying to do. I didn’t know she was doing this kind of study. I only thought she was in the dancing environment.”

De Palma didn’t plan to become an activist. She wanted to be a dancer. But that changed on a visit to Peru, when she saw the impact of oil drilling on the environment and local indigenous groups.

When she came to the US, she eventually landed a job with the Audubon Society. She’s helped the organization win at least some small victories where the water meets the rising sea in south Florida.

She says it helps that she lives in the area herself, rather than coming in from outside.

“Living in areas where you’re going to be more prone to have floods, you are in a unique position to exert pressure onto your elected officials and help us prepare for sea level rise,” De Palma says.

Among other things, she recently helped keep developers from building a new mall near the Everglades.

On her tour of Florida Bay, thousands of wading birds feed far off in the distance, standing in a foot of water.

It’s not hard to see the birds as a metaphor for what could lie ahead for people here in south Florida, Hispanic and otherwise.

But for De Palma it’s not about standing still, waiting for the inevitable. It’s about taking action.