How an American scholar saved a trove of Tibetan literature from extinction

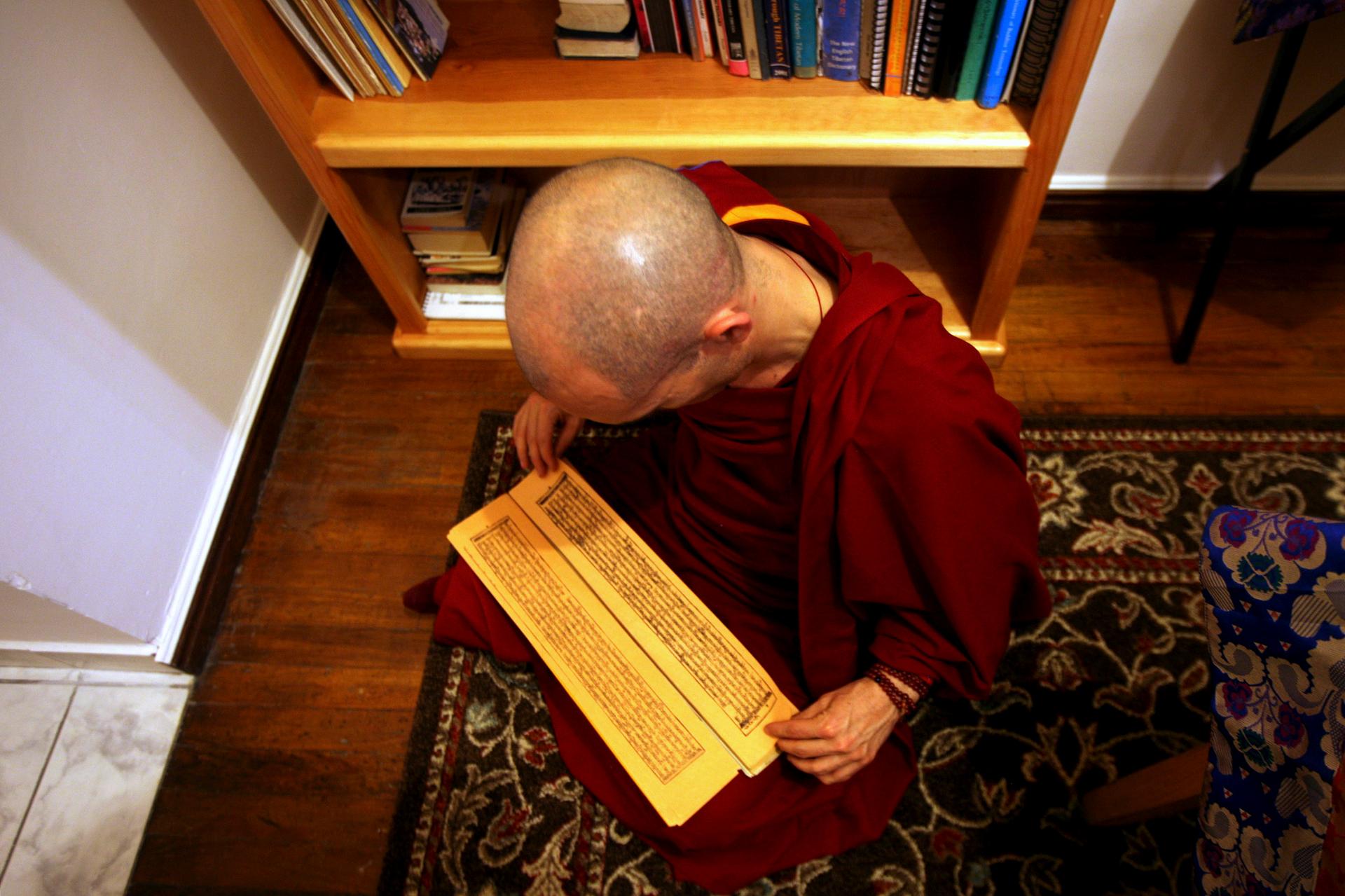

A Tibetan Buddhist monk reads from a traditional Tibetan book sitting in his lap.

The first Tibetan monks who moved to the United States soon after the failed 1959 uprising against Chinese rule in their homeland found some eager American students of Tibetan Buddhism. One of them was Gene Smith, a Mormon from Utah and a linguist who quickly immersed himself in the study of Tibetan religion, language and literature.

The problem for Smith, however, was a shortage of study materials.

At the encouragement of his Tibetan teacher, Smith began his quest to collect and preserve works of traditional Tibetan literature. It became his life's mission, and it soon took on a sense of urgency as Chinese policies in Tibet threatened its body of Buddhist scripture. People all over China suffered during the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976, but Tibet was a special case.

Radical red guards targeted anything they perceived as "backwards" or "feudal" for destruction. That included Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, religious works of art and traditional literature. Thousands of Tibetan books were burned during that decade of upheaval. But some were hidden away, or smuggled out of Tibet. Smith went about collecting as many of them as possible. Eventually, he amassed the largest private collection of Tibetan literature in the world.

"[Smith] spent basically 25 years, first in Europe and then in India, looking for these lost texts," says Andrew Jacobs of the New York Times. "He collected thousands over the years and ended up printing many of them, and he saved a copy of every book he printed."

Smith, who died in 2010, set up an institute for Tibetan literature in Cambridge, Massachusetts. But he also long hoped to establish a library of Tibetan works in Asia. That dream came true last October, at the Southwest University for Nationalities in Chengdu, China. The university opened a library of 12,000 Tibetan-language works.

"The university paid for the library and Gene Smith donated the books," says Jacobs, who visited the library in Chengdu and wrote about it in the newspaper." The newspaper also produced a video at the museum.

"It looks like a Tibetan temple," he explains. "It's a pretty impressive space."

Jacobs says word has gotten out about the library, and more works of Tibetan literature are now being taken out of hiding and brought to the library to be shared and preserved.

Smith's efforts haven't been immune to politics, though. Soon after he made the deal with Southwestern University, ethnic riots broke out in nearby Tibet. The library project was put on hold. Jacobs says he has heard complaints that the facility is not as open and freely accessible as some experts would have hoped.

"But it is there and it is available, for the most part, and I think it's seen as a great resource for scholars," he says.