For New York City’s aging immigrants, it can be hard to create a community

According to a report from the Center for an Urban Future, the elderly Korean immigrant population in New York City is the least proficient in English.

At a McDonald's in the heavily immigrant neighborhood of Flushing, Queens, customers stream in and out during the morning, buying coffee and breakfast as soft rock plays in the background. Most of them are Koreans and Latinos.

This particular McDonald's made headlines recently when New York police officers were called to toss out a group of elderly Korean patrons. McDonald’s management claimed that they were hanging around too long. The two sides finally reached an agreement about when and how long customers could linger.

For Pak Ilho, an elderly Korean who sipped coffee with friends and read a newspaper at the McDonald's recently, the incident was an embarrassment for him and his Korean friends. He doesn’t understand why the cops had to get involved.

Pak and his friends say this McDonald's is a great, convenient meeting spot. The place is airy, with large windows that look out onto a bustling intersection. A Korean grocery store and church are nearby.

A few tables away, 77-year-old Jeung Hyon Suk has a lot to say about what happened here, too. But when I asked why she didn't visit with friends at a nearby Korean senior center, she called to a woman sitting nearby and asked if she knew what place I was talking about.

Despite the fact that the senior center is relatively close to the McDonald's, Suk had never heard of it before.

This is hardly a surprise for Christian González-Rivera, a researcher at the Center for an Urban Future, a New York-based think tank.

"Most practitioners in the senior-services world say there are a lot of services available, but the problem is that immigrant seniors aren't reaching out, or aren't able to access them in one way or another,” said González-Rivera.

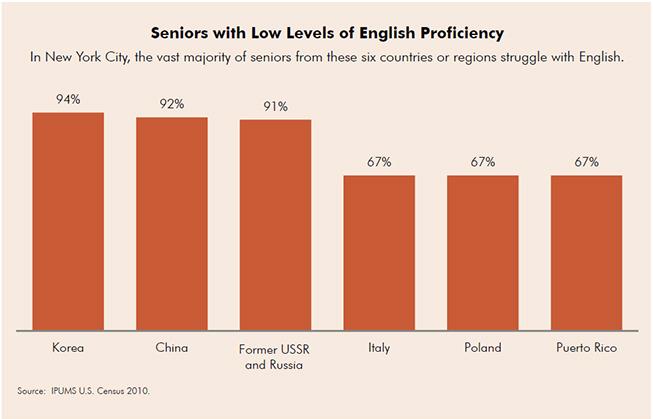

Language barriers can make it especially hard for these seniors to access services, like a senior center. And this is especially true for Koreans, who, according to the Center's recent report on aging New York immigrants, are the least proficient in English compared to other older immigrants in the city.

Why? It’s partly because many Koreans moved to the United States later in life. “Therefore, not assimilating into American culture, not being able to speak the language, and being concentrated in their own enclave means that they've had very little contact with opportunity outside of their community,” said González-Rivera.

To see some of the challenges facing Korean senior centers, I headed to the Bronx Korean American Senior Center. It's about a 30-minute drive from the McDonald's in Queens. When I got there, the center's weekly computer class was just getting started. Five Korean seniors hunted tentatively around the keys, learning basic keyboard shortcuts.

Most of them live near the center, which is a small space consisting of two rooms and a small kitchen tucked in the back of a plain brick building. But Andrew Suh told me that he comes here from New Jersey, an hour-and-a-half trek by bus and subway. He said the senior center near his home doesn't cater to Koreans.

I asked him why he was working on his computer skills. "I like writing, and email, and today, I want to open Facebook,” he said. His main connections would be friends and family back in South Korea.

This center opened more than 20 years ago and stays afloat thanks to a small grant from the Korean American Community Foundation. The center is a big help for the 30 or more Koreans who drop by most weeks.

Along with computer classes, there’s an English class, a dance class and the center serves a Korean lunch.

Abraham Lee, the center's director, said he would love to do more, but funding is hard to come by. Going for big grants or government help means lots of bureaucracy and English expertise. Also, bigger donors hesitate to fund small groups.

To try and bridge the gap, the Korean foundation just launched a fellowship that pairs young Koreans with groups like Lee's, hoping that, together, they can solve the funding puzzle.

Like the people at McDonald’s, senior Andrew Suh from the computer class was eager to talk, and he wanted to practice English. He says he's always checking English books out of the library. "A lot of American books! I want every books, want reading, but my English is no good,” he said with a laugh.

But he's committed. He says before he dies, he's going to conquer the English language.

Update: An earlier version of this story showed that the Center for an Urban Future reports that the elderly Korean population was the least profient population in the US. However the Center's report only looks at the New York City population.