The history of electronic surveillance, from Abraham Lincoln’s wiretaps to Operation Shamrock

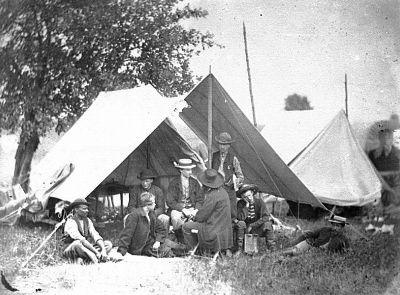

Union army telegraph operators just after the battle of Gettysburg. The Civil War is sometimes described as the first information war. Intercepted messages landed on Abraham Lincoln’s desk.

Did you hear the one about AT&T?

It's no joke.

The New York Times, citing government officials, says the company is receiving $10 million a year from the CIA to "assist with overseas counterterrorism investigations." This allows the CIA to exploit AT&T's vast database of phone records, especially international calls.

Whether right or wrong, government surveillance goes way back.

It goes back to the first electronic media: the telegraph. The name AT&T originally came from the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, although the corporation that bears the abbreviated name today is much changed. Messages were sent over telegraph wires by the dots and dashes of Morse Code, then typed up and delivered as telegrams.

That was the first security problem: you delivered your message to a person who would transmit it to one or more operators around the country or the world. The personnel could physically leak the content of your message. Or physical copies could be stolen.

Then, of course, eavesdroppers can literally tap the telegraph wire anywhere along its length — the first wiretapping — to listen to a message. Some US states introduced legislation against this kind of thing as early as the 1860s, and imposed heavy penalties on personnel disclosing content. But governments weren't too concerned with privacy then either, especially when national security was involved. Intercepted telegrams routinely landed on Abraham Lincoln's desk during the Civil War.

In response, individuals and organizations engaged "telegraph security consultants" to maintain their privacy. Their responses centered on using codes and cyphers — something the telegraph companies were not too happy with.

Mass surveillance really got underway about a century ago, just before and after World War I — again at a time of intense concern over national security. Only then did countries find it worthwhile to invest in it — the cost had been prohibitive, given how labor intensive it was before the age of computerization.

Here in the US, all interference in electronic and wireless communications was illegal but that didn't deter US military intelligence. A so-called "Black Chamber" was set up, and in 1920 its officials very easily cut a deal with Western Union to intercept whatever they were interested in.

By this point in history, the telephone was becoming common, and again it was technically very easy to tap into a telephone line and listen in to a conversation, but again logistics make it tricky to do en masse. Phone tapping was ruled constitutional in 1928 for law enforcement and was used against gangsters in the prohibition era.

Other than fighting gangsters, surveillance was ostensibly carried out mostly to help with national security. The same was largely true in other western democracies. But in the authoritarian states emerging in 1920s and 30s in Europe, surveillance was used for much more sinister purposes.

In the US, the surveillance system was temporarily halted in 1929 by Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson. Just after taking office, he was presented with intercepts of Japanese military cables, and he famously said "Gentlemen do not read each other's mail." Some historians argue that may not have been a great move for national security, since arguably it helped the Japanese achieve surprise at Pearl Harbor.

In the aftermath of World War II, the US saw its first truly comprehensive mass surveillance program, called Operation Shamrock. It was designed to catch Soviet spies, and it came under the NSA when the agency was established in 1952. Shamrock was massive, and massively intrusive. Every day, usually around midnight, the nation's telegraph traffic was collected from corporate offices in New York, in the form of punch cards, and couriered over to the NSA office for copying and then returned to the telegraph companies. The program was shut down amid shock and outcry when it was exposed in the 1970s, when the modern rules and regulations governing surveillance were established — rules which now appear to many to be out of date.

Two great books on these subjects are "The Victorian Internet" by British science writer, Tom Standage; and "The Puzzle Palace" by James Bamford.