A Soviet Memoir From the Standpoint of the Stomach

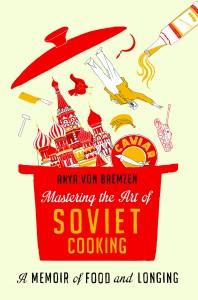

Mastering The Art of Soviet Cooking

It's all there, and more, in a new book called "Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking." It's by award-winning cookbook author Anya von Bremzen, but it's not a cookbook. Her new book is both a family memoir and a survey of Soviet history – from the kitchen table.

Von Bremzen has always had a complicated relationship with food. She says it's just part of her heritage. She was born in Moscow in l963.

"I grew up in an apartment where 18 families shared one kitchen."

She says food was enormously important in virtually every era of the Soviet Union's tumultuous history.

"It was the most essential issue, from the revolution, until the very end."

That's both politically and personally, because the Soviet state didn't only dictate where its 300 million citizens worked and lived, but also what they put in their mouth, which most of the time wasn't much.

"Any period of my Soviet life, it was lack of food, it was shortage of food, it was difficult to buy, it was difficult to find, food became kind of obsession for most Russians," says von Bremzen's mother, Larissa, now 79.

She remembers her own mother's heroic efforts to feed her family during the hungry years of the Second World War. They didn't starve, but they rarely had enough to eat.

"We always wanted something sweet," Larissa says. "It was really a terrible thing for children not to have anything sweet."

For Larissa, a slab of black bread sprinkled with a few granules of sugar was a heavenly treat.

As an adult, Larissa loved to cook. She had grand ambitions, but not much to work within the way of ingredients, so she and her young daughter Anya feasted vicariously, devouring descriptions of freshly salted caviar, flaky fish pies, and racks of lamb in the stories of Gogol and Chekhov.

Anya von Bremzen describes it as "orgiastic food porn" from 19th century Russian literature.

"We just imagined what this stuff tasted like. We had absolutely no idea," she says. "Or my mom would read Proust or Hemingway and we'd go to sleep wondering what do you think a madeleine really is, is it a jam-filled pirozhki? We had absolutely zero idea what pizza was."

When Anya was almost 11, she and her mother immigrated to the Land of Plenty. This was in l974. They were among the first wave of Soviet Jews who were allowed to emigrate. They ended up in Philadelphia.

"I'll never forget our first trip to the Pathmark. It was as huge as Red Square, and just packed with absolutely everything. And my mother would go swooning, 'oh Cheerios! Velveeta!' She was so excited."

But that's not how Anya felt. She says it was like the death of her desires. "Because once you saw the abundance, who cared? It lost its value. I think it was then, at the age of 11, that I realized the multiple meanings of food every morsel of food can be packed with."

Von Bremzen realized that imagining food was a lot more thrilling than having it. Besides, she didn't even like American food. She wanted Moscow bread, not Wonderbread. She found Pop Tarts and peanut butter revolting. She was miserable.

So she escaped into music. She graduated from Juilliard, with hopes of becoming a concert pianist. Then a new problem arose. Her wrist started to swell.

"There was like this plum sized thing on my wrist, which is called a ganglia."

Her teacher said Anya's technique was all wrong, and that she'd have to start from scratch.

"So I was playing scales again. I was 24 and absolutely miserable."

To earn money, she translated a cookbook from Italian, a language she'd learned during a brief sojourn in Rome.

"Here I was thinking about allegro con brio and andante spianato, and writing about spinach and pesto," she says. "Then I though, huh, this is interesting – cookbooks."

By the time she'd finished, the lump on her wrist was nearly gone, but so was her passion for piano. Writing Italian recipes had unexpectedly reawakened her obsession with food.

"I think food was really deep in my psyche, and it represented so much more than, yum yum, what you put in your mouth."

It also represented power and prestige; lives lost and longing.

Von Bremzen decided to write her own cookbook, about the ethnic cuisines of the Soviet Union. She says it wasn't an easy sell.

"Everyone said: 'Russia, are you kidding? Is it a book about breadlines?' "

But she eventually found a publisher. "Please To The Table" became an unexpected best seller, and won a James Beard Award. Her timing was interesting; the cookbook was published in l990, the year the Soviet Union began to crumble.

"It was kind of a book about the culinary friendship, whole multi-ethnic Soviet melting pot with all the republics, while all the republics wanted out, they were separating. So my friends joked that it should be a tear off calendar. Uzbekistan's going! Ukraine's going!"

Von Bremzen parlayed the success of "Please to the Table" into a successful career as a food writer and restaurant critic.

"Here I was traveling the world and dining at places like El Bulli and Per Se, eating foie gras. And the shadow of my former life, the complex relationship with food would almost be in every bite."

Anya Von Bremzen decided to confront that shadow. "Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking" isn't just her story. It's also the story of millions of ex-Soviets; people who remember the rapturous sensation of biting into an orange, which they could only get once a year.

Anya von Bremzen isn't nostalgic for the USSR, but she does feel like her Soviet childhood was special.

"I mean, who else grew up singing odes to Lenin and wearing a Young Pioneer tie and putting so much meaning and existential significance into everything that you ate?"

She says it's surreal to come from a country, and a culture, that no longer exists.

"Now we're looking at the ruins of it. It's like this incredible interior, exterior archeological site that is part of our psyche."

Anya Von Bremzen has retrieved from those ruins something so essential, and obvious that it was hidden in plain sight.