US and China Prepare Cyber Defenses in Face of Increased Hacking Threat

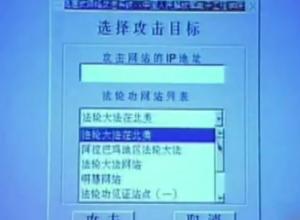

A video grab showing an alleged “cyber attack.” (Photo: YouTube)

China’s in a rush to catch up with and surpass the United States, and evidence suggests that hacking into and stealing data from the computers of strategic US companies, research labs and government departments is one of its favored tools.

Hackers in China are now considered among the world’s best, and certainly most prolific, and Washington is amping up its efforts to thwart the threat.

A cramped little office, in a hastily developed area of Beijing that still feels half-rural, is home to one of China’s first self-described “patriotic computer hackers.” He talks about how it all began, in college, a couple of decades ago.

“When I took a computer class, and I found an interesting thing called a ‘computer virus.’ A computer virus is a small-size program. If I can learn how to make a computer virus, I can get a special skill,” said Wan Tao.

Wan’s now edging up to middle age, and is, these days, a cyber-security consultant to a large western company. Back then, he was a student at Beijing’s Jiaotong University, known for its computer studies programs. And for turning out some of China’s better cyber-hackers. Wan Tao found his stride as a patriotic hacker in 2001, incensed that a Chinese pilot was killed while trying to thwart a US spy plane.

“So 10 years ago, I was an angry young man. I thought ‘Chinese nation is a great nation and we are powerful and we need to be powerful and not so weak,'” Wan said.

So Wan Tao assembled a group of more than 100 hackers, called China Eagle Union. It defaced about a thousand US websites, and put a couple of US government websites under denial-of-service attacks. That was kid stuff, compared to what other Chinese hackers have gotten up to since.

Alan Paller is the director of research at the SANS Institute in Washington DC, which does cyber-security training. He first became aware of this new breed of cyber-attack from China in 2005, when one such attack came from a server in the southern province of Guangdong, It targeted Sandia Laboratories which, among other things, designs and tests nuclear weapons.

“They came into one site,” Paller said. “They found the data that they were looking for. They tarted it up. They hid it in areas of the disk that aren’t easily found, so if they got knocked off they could come back and get it without leaving any evidence. They cleaned up the logs, so there was no record of their having been there. And they did all of that in 30 minutes with no keystroke errors. And they were doing that 24 hours, 7 days a week, from 20 workstations.”

Which led Paller to conclude it was probably an attack by the Chinese military. Many subsequent attacks have been traced back to servers in China, including to the Beijing headquarters of the Public Security Bureau. Even a documentary last July on China’s state-run television, CCTV-7 had incriminating evidence.

What caught international attention was a few seconds showing a Chinese computer screen apparently in the act of launching a cyber-attack on an overseas website linked to Falun Gong, a spiritual group outlawed in China.

Still, China’s official reaction to accusations the government is involved in hacking is to be affronted, as in this comment last year by Foreign Ministry Spokesman Hong Lei.

“Hacking is an international problem, and China is also a victim,” Hong said. “Anyone who suggests the government supports hacking has ulterior motives.”

It is true that China is also the victim of hacking, most recently by the hacker Hardcore Charlie, who poached email from the server of China Electronics Import & Export Corporation, or CEIEC. That was embarrassing for them, not only because the group deals in defense electronics, but also because the hackers found and made public what appeared to be stolen documents detailing deliveries of supplies to US military facilities in Afghanistan.

James Lewis directs the Technology & Public Policy program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

“I don’t burst into tears that they are doing this. There’s a point where you’ve gone sort of past what is internationally acceptable and they’re well past that point,” he said. “Some people got really indignant ‘How dare they spy on us?’ Of course they are gonna spy on us. What I get indignant about is we have been so inept in responding to it.”

By “it,” he means a massive and accelerating effort by Chinese hackers — official, unofficial, and everything in-between — to invaluable strategic and economic data, sometimes whole industries-worth, from the United States and elsewhere.

Lewis leads a set of talks and war games with Chinese counterparts on cyber issues, called Track 1.5 Diplomacy. One goal is to prevent cyber-attacks from escalating into military hostilities, something the Chinese don’t want.

“They’re pulled in two directions. They don’t want to fight with the US. They like the fruits of espionage because they really get some good stuff. So I detect a really high degree of ambivalence, sort of a conflict. They like doing it. They know it’s painful. So they are not at a point where they are willing to give it up, absent some kind of external pressure,” Lewis said.

President Obama has pledged to get tougher on cyber-espionage and possible cyber-attacks from China and elsewhere. Just last month, the Administration simulated a cyber-attack on New York City’s power supply as a demonstration for senators, who are considering two competing cyber-security bills.

Alan Paller said while the political dickering goes on, US entities, including companies, need to defend their data. And not just the companies you’d think. He said Britain’s intelligence chief knows that.

“The head of MI5 sent a letter to the largest 300 companies in the UK, saying, ‘if you are doing business with these guys, they are attacking you with exactly the same tools they are using to attack the military,'” Paller said. “And the reason they’re doing it is they want your playbook. He also said, ‘they’re coming after your lawyers.’ The lawyers often have the playbook for the company in an easier-to-find form than the company itself.”

If any more incentive to take preventative measures is needed, former hacker Wan Tao gives a window into how Chinese hackers think.

“I don’t think hacker economics means crime,” he said. “‘Hacker,’ to some degree, means searching for the truth. Hackers are just action people.”

Wan Tao said, on the Internet, information wants to be free, and information in someone’s bank account, or in a company’s email account is just more information.

That said, he did initiate a code of conduct last year urging other hackers not to hack for profit. Asked whether he thinks Chinese government information wants to be free, too and whether he ever tried to hack that, wan said.

“No, the Chinese government would take that action as a computer crime action.”

They certainly would consider it a crime.

But the government has been known to turn skilled cyber-hackers to work with the government. I ask Wan Tao if they ever offered him a job, or if he was ever interested.

No, he said. A nine to five job was never his thing.