Study find certain U.S. regions can keep poor people poor

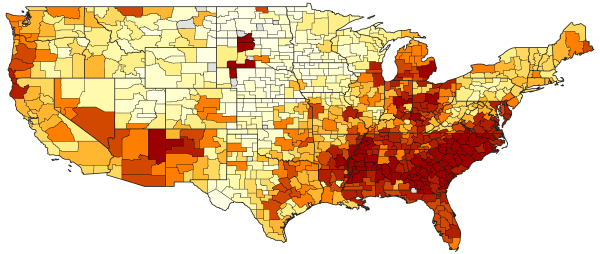

A map depicting areas where children from low-income families are more likely to move up in class. Lighter colors represent more favorable areas. (Courtesy of Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez)

The probability that a child from a low-income home will reach a higher economic bracket when they reach adulthood, a metric known as mobility, holds a strong correlation to the region where, according to a new study by economists from Harvard University and University of California Berkeley.

While studies on income inequality generally measure wealth gaps between high- and low-income families, the new study takes a different approach. Instead of capturing a moment in time, it shows the long-term term effects of location on economic mobility.

“If you think about it, mobility matters more,” said David Leonhardt, Washington bureau chief for The New York Times. “We don’t just want to know how people are doing in a moment in time, we want to know how they’re doing over their lives.”

Southeastern cities like Atlanta, Charlotte, Memphis and Raleigh, as well as industrial Midwestern cities like Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Columbus, all ranked as places where upward mobility is most difficult.

Children from low-income families fared best in Northeastern cities like Pittsburgh, Boston and New York, and in Western cities like Salt Lake City and Seattle.

Despite some outlying cities like Atlanta, the United States has a stronger mobility rate on average than other developed countries like Canada, France and Japan.

Using millions of anonymous earnings reports, the study was able to pinpoint four factors to determine whether a metropolitan area helps lower class children rise out of poverty: education, family structure, civic engagement and economic integration of the affluent and the poor.

When job opportunities are concentrated in areas where only the affluent live, it becomes difficult for the poor to tap into them.

“Atlanta is a famously sprawling metro area and it’s got pretty bad public transportation,” Leonhardt said. “So I talked to people who lived in a tough neighborhood and it would take them two hours to get to a decent job in another neighborhood.”

Civic engagement measures the level of interaction in a community in places like churches, youth leagues and bowling alleys. The higher the civic engagement, the more likely poor people are to hear about opportunities or make connections they wouldn’t have otherwise.

“Some of it is just the idea that when people are out in organizations spending time together, it sort of builds a social fabric in a way that’s probably difficult to fully capture with words or numbers, but that just makes a place function a little bit better than in a place where people are isolated,” Leonhardt said.

The study also found that children who moved from a low-mobility area to a high-mobility area had about the same success rate as children who spent their entire childhoods in the high-mobility area. However, people who made similar moves later, as teens, were less likely to succeed than the children who grew up there.