Part IV: The Infectious Connection

Veronica Alebo, a young Burkitt’s lymphoma patient, has a large tumor in her abdomen. She receives treatment at the Uganda Cancer Institute in Kampala.

This story is part of a special series, Cancer's New Battleground — the Developing World.

More than half a century ago, an Irish physician named Denis Burkitt moved to Uganda and opened a medical clinic.

He was quickly struck by the large number of children with grotesque facial swellings that often grew large enough to choke and kill. It was a type of cancer he had never seen back home.

The cancer came to be called Burkitt's lymphoma.

Today on the pediatric ward at the Uganda Cancer Institute, the beds are filled with children with Burkitt's. It’s the most common childhood cancer in equatorial Africa.

And it starts with an infection.

“It's associated with a virus called Epstein-Barr virus,” says the institute’s Dr. Abrahams Omoding.

Epstein-Barr virus, which also causes mononucleosis, appears to initiate Burkitt’s lymphoma. Malaria may also play a role in triggering the disease.

Cancer-Causing Germs

“People usually think cancers are caused either by bad habits” such as smoking or alcohol use, Omoding says, or by eating the wrong things, being exposed to radiation or chemicals, or aging. But many infections can also cause cancer.

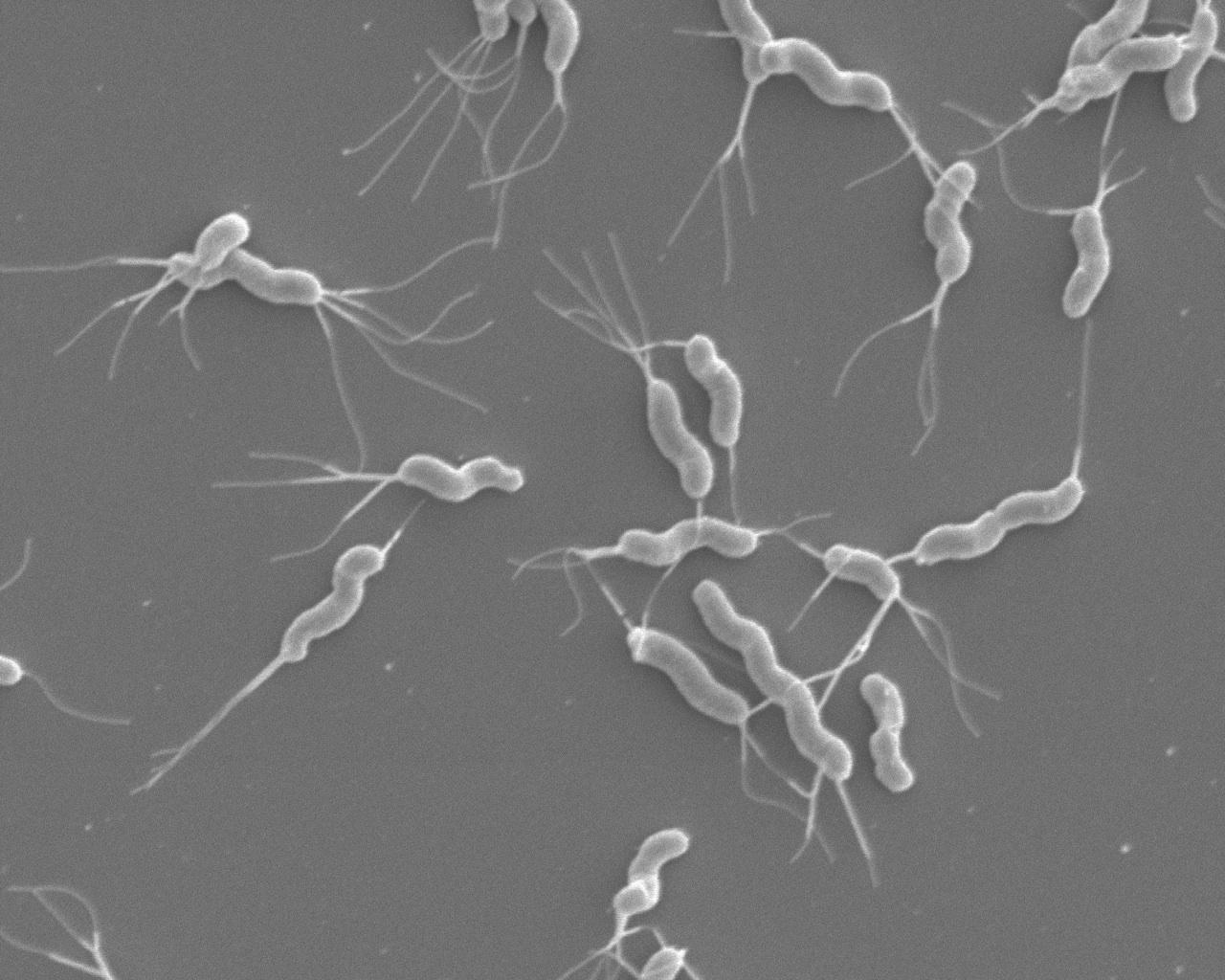

Bacteria called H. pylori, which cause ulcers, can sometimes cause stomach cancer.

The parasite responsible for schistosomiasis, a tropical disease, can lead to bladder cancer.

Cervical cancer is caused by the human papillomavirus.

“We’ve [also] got liver cancer,” adds Omoding. “It's associated with hepatitis B virus.”

And there’s Kaposi's sarcoma, caused by a virus that attacks people with weak immune systems. In Uganda, where many people are HIV-positive, Kaposi’s sarcoma is in epidemic proportions.

And there’s Kaposi's sarcoma, caused by a virus that attacks people with weak immune systems. In Uganda, where many people are HIV-positive, Kaposi’s sarcoma is in epidemic proportions.

“The list is long,” says Omoding. “These are the most common cancers that we see, and all of them are actually virus-related. [It’s] different in the US.”

In North America, only one in 25 cancers can be blamed on infectious agents. In developing countries, it's one of every four cancers, according to a recent study in the medical journal The Lancet Oncology.

The reason? Poor sanitation in developing countries means greater exposure to germs. In addition, people in places like sub-Saharan Africa aren't likely to be vaccinated against viruses that can cause cancer, such as the hepatitis B virus.

Deciphering the Link

8,800 miles from Kampala, in Seattle, Washington, scientists at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center are trying to figure out how viruses cause cancer.

In Mei Lei Huang's laboratory, researchers get shipments from Uganda every other month.

“If it's [a] blood sample or tissue, it will come in dry ice,” she says.

The samples go in freezers that line one wall.

The samples are part of a study of Burkitt's lymphoma. Scientists want to determine how long the cancer takes to develop after a child is infected with Epstein-Barr virus.

Larry Corey, head of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, says the work is aimed at one goal. “Can we intervene? Can we alter the underlying development of cancer by attacking the virus?”

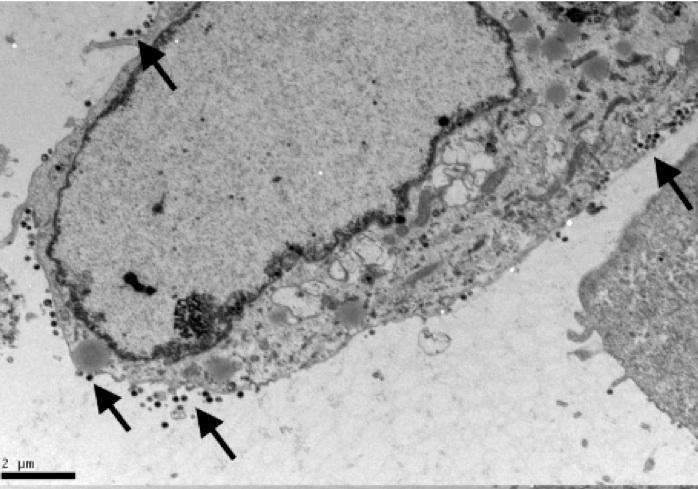

The biological link between infections and cancers works like this: Invading organisms infect cells and disrupt the cells' normal workings. The Epstein-Barr virus, for example, infects immune system cells called B cells and causes them to grow.

“The more they grow, the more they divide,” Corey explains. “The more they divide, the more the chance there is of an alteration of the genetic material during the division phase.” That alteration causes cells to grow out of control and become cancerous.

“The more they grow, the more they divide,” Corey explains. “The more they divide, the more the chance there is of an alteration of the genetic material during the division phase.” That alteration causes cells to grow out of control and become cancerous.

The Goal: Prevention

But Corey says there is good news about infectious organisms and cancer: The link between the two can be broken.

“If you know an infection is the cause of cancer, if you attack the infection, you can actually prevent the cancer.”

That is already happening with the HPV vaccine, which protects against many of the viruses that cause cervical cancer and some other cancers.

Similar success is being seen with hepatitis B. It can lead to liver cancer—a leading cause of cancer death in China—but thanks to vaccine programs that began in the 1990s, liver cancer deaths in China have begun to drop.

There is no vaccine yet that can prevent children in Uganda from getting Burkitt's lymphoma, but Corey's scientists in Seattle and their colleagues in Kampala are working on it—together.

Corey's long-term dream is to see vaccines against all infections related to cancer. If achieved, that would drop the world's cancer death rate by about 20 percent.

This series was produced with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.