Norway’s oil and gas boom leaves other European economies lagging behind

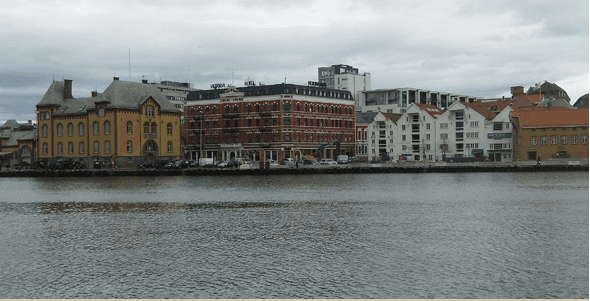

The city of Stravanger has grown wealthy from oil industry proceeds over the last few decades. It is now one of the most expensive cities in the world. (Photo by Laura Lynch.)

Offshore drilling has transformed Norway’s economic and physical landscape.

In the pretty harbor city of Stavanger on Norway’s North Sea coast, herring canneries are being replaced by high-end fashion stores.

Piers Croker, the curator of the Norway Canning Museum, said canning was the lifeblood of Stavanger.

“Fifty percent of the working population was employed in the canneries; another 15 percent in the supply industries,” Croker said. “And there was a newspaper headline in the 1920s, ‘The City that Stands on One Leg,’ and that leg was canning.”

Jobs in the canneries disappeared quickly in the 1980s and were replaced by positions in the oil industry.

“There was a guy who had been in the in canning industry for 30 years. And his wages, when he retired from the canning industry, were less than his 18-year-old daughter (was making) beginning in the oil industry,” Croker said.

The harbor is dotted with cranes and offshore oil platforms ready to float out to North Sea drilling sites, and the streets are lined with high-end fashion shops. In recent years, Stavanger has become one of the most expensive cities in the world.

The long term success of Stavanger is due to the country’s tight economic management. Norway has avoided the so-called “Dutch disease” that has befallen other countries when they’ve struck oil. Norway’s success, some say, is largely due to one man, Farouk al-Kasim.

Al-Kasim moved to Stavanger with his Norwegian wife and family in the late 1960s from Iraq where he worked as a geologist for the state oil company. When one of the world’s largest oilfields was discovered off the coast of Norway, Al-Kasim was hired by the government to help devise a strategy for managing the valuable resource.

Al-Kasim said one of the first things Norway did right was to control its newfound wealth.

“You don’t really benefit at all by allowing oil revenue to come onto you like a tsunami and flood everything. That will completely destroy non-oil sectors of the economy,” he said.

Norway had watched that scenario play out in The Netherlands in the 1970s. Following a a boom in oil exports, money flooded into the domestic economy inflating the currency. The Netherlands was loaded with price increases that destroyed exports and led to unemployment and inequality.

By contrast, Norway has held on to almost all of the revenue it earns in an ever-growing savings account, known as the “oil fund.” It now holds almost $600 billion and is one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world.

Petter Osmundsen, a professor of petroleum economics at the University of Stavanger, said the small amount the government withdraws from the fund for spending each year — four percent — is more than enough.

“We have been spending a lot of money so even this four percent is a very good increase in public budgets over the last years with good oil price and high oil production,” he said. “We are not starving.”

Norway is busy devising the best strategies to develop its wealth in the years to come. On Thursday, Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg and his British counterpart David Cameroon agreed to a new energy partnership between the two nations. The “Norway-U.K. Energy Partnership for Sustainable Growth” will ensure long term exports of Norwegian gas to the U.K.

But the success of Norway’s oil and gas industry has created some challenges. Osmundsen said the global financial crisis has made Norway almost too successful in comparison to its neighbors.

“We are having good times whereas the others are having bad times,” Osmundsen says. “So we keep getting pay rises whereas the other countries are getting pay cuts. If this lasts for a number of years the Norwegian competitiveness will be reduced in other industries than the oil.”

So earlier this month, Norway decided to cut its spending from oil income by a billion dollars to slow economic growth.

None of this seems to bother Norwegians. The fund holds more than one $100,000 for each citizen, but they seem content to save for the future and continue to pay high taxes.

Al-Kasim isn’t surprised by this attitude. He thinks the impact of Nazi occupation during World War II left a lasting legacy on Norwegian society.

“This sense of belonging together, being completely not only dependent on each other, but trusting each other, this solidarity in the nation was absolutely unique,” he said.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?