Businesses prepare for explosion in deep sea mining activities

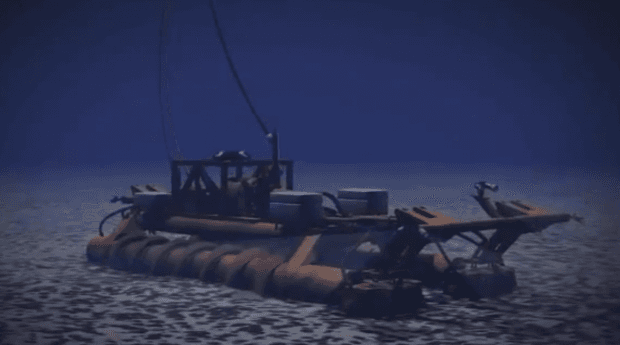

This computer generated image from Lockheed Martin suggests how the company could mine manganese nodules from the sea floor, using underwater vehicles that vacuum up nodules and transport them to a ship on the ocean surface. (Photo courtesy of Lockheed Ma

After decades of dreaming and scheming, companies say they’re finally ready to start mining the bottom of the world’s oceans for valuable minerals.

For Adrian Glover, a marine biologist at London’s Natural History Museum, the furthest depths of the seas are familiar territory.

He shows a photograph of a flat, seemingly barren terrain nearly two and a half miles down — part of what’s called the abyssal Pacific Ocean floor, off the coast of the United States.

Glover says it’s an area almost the size of the U.S., and the sea floor there is carpeted in potato-sized accretions known as manganese nodules.

He handles what looks like a lump of coal, but the material is surprisingly light and crumbly.

“They’re peculiar things,” Glover said. “They were first studied in the 1960s, and people quickly realized that they’re rich in minerals.”

Among the minerals are not just manganese but also copper, cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements — materials essential these days in the production of everything from high-grade steel to smart phones and tablet computers.

Stephen Ball of Lockheed Martin says the global appetite for these sorts of minerals is growing all the time.

Lockheed is a defense contractor that hopes to be among the first to get into the deep-sea mining game.

But the company has a long, strange history in the development of the industry. It’s an elaborate tale that involves a top-secret CIA mission during the Cold War, and the eccentric American billionaire Howard Hughes.

The short version of the story begins when Hughes was hired to go look for a lost nuclear-armed Soviet submarine that sank deep in the Pacific Ocean in 1968.

Ball says Lockheed worked with Hughes to help raise the submarine in the 1970s to collect intelligence on the Soviet military.

The official story at the time was that the mission was actually a search for manganese nodules.

Ball says the effort actually did involve surveying the ocean floor, which ended up giving the company detailed data on the nodules.

It’s only now — with rising mineral prices and new technologies — that mining the deep sea finally looks economically viable. And earlier this year, the International Seabed Authority granted a British subsidiary of Lockheed an exploration license for a huge stretch of the Pacific.

The company’s plan calls for vehicles to rove across the sea floor scooping up nodules like a vacuum cleaner and sending them up pipes to ships on the surface.

But of course this type of mining has never been done before, and it raises a raft of environmental concerns.

To begin with, although the bottom of the deep ocean looks barren, it’s actually teeming with life. And Rod Fujita, of the Environmental Defense Fund, says no one knows how long it would take these ecosystems to bounce back from mining.

“The recovery rates are likely to be very, very, very long,” Fujita said, “because biological productivity is very low, and growth rates are very low down there.”

In fact, some ecologists are very blunt on the matter.

George Woodwell, of the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, calls deep-sea mining “just plain crazy.”

Woodwell says the operations would be highly destructive and could disrupt the chemistry of large parts of the oceans at a time when they’re already under stress from climate change.

Lockheed Martin says it takes environmental concerns seriously. In line with international rules, the company says it’s collaborating with scientists like Glover to study its patch of the sea floor before it mines.

In fact, some marine biologists see teaming up with industry now as an opportunity to lay effective ground rules before full-scale mining gets underway.

Cindy Lee Van Dover of Duke University says the people involved “have to get it right.”

We don’t want a hundred years from now conservation scientists to say, ‘Oh my god, what they were they thinking?'” she said.

Van Dover has worked with a company that plans to mine another type of mineral-rich deep-sea ecosystem known as hydrothermal vents. She’s conflicted about the work, calling herself a tree hugger who’s spent her life studying the deep sea animals. But she says she has to be pragmatic. It isn’t a question of right or wrong.

“It’s going to happen. And I think it can happen in a way that we can get the minerals and still protect those animals,” she said.

If it is going to happen, it’s because there could be lots of money to be made — more than $60 billion over thirty years for U.K. businesses alone, according Lockheed Martin.

The company hopes to realize that bonanza in the next decade and plans to begin environmental research in the Pacific this summer.