American veteran of Spanish Civil War remembers life under suspicion of communism

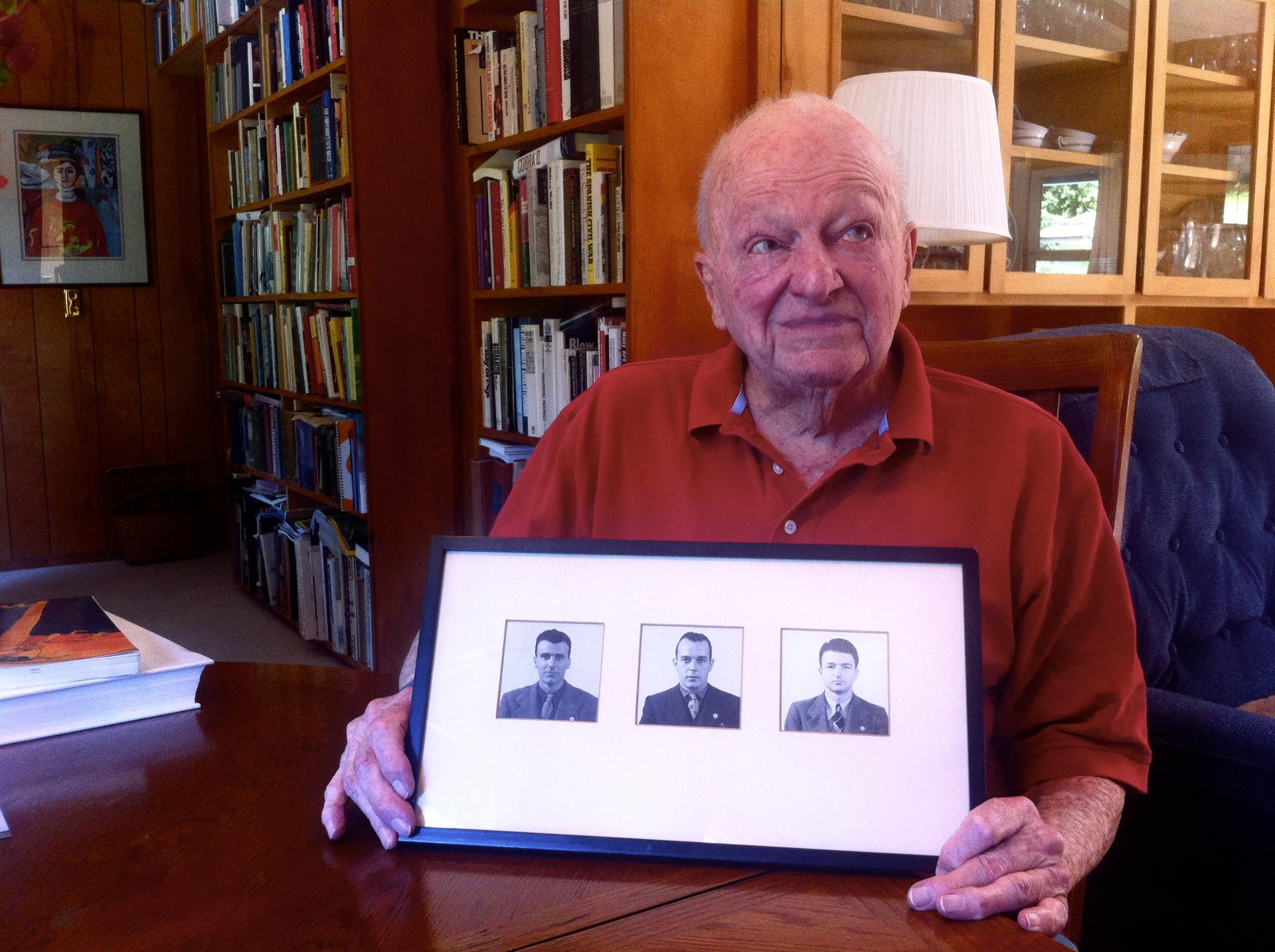

James Benét volunteered to fight in Spain’s 1930s Civil War. (Photo by Monica Campbell.)

In the 1930s, nearly 3,000 American men and women volunteered to fight in Spain’s Civil War, against General Francisco Franco and his fascist forces.

About 900 of these vets, known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, were killed in fighting. Today, only four are still alive to tell their story. One of them, James Benét, is now 98 years old, living in rural northern California.

From his home in Forestville, Benét recalls leaving for Spain in his early 20s. At the time, he was a journalist living in New York, a socialist raised in a military family. So when he heard about Americans united by their anti-fascist views heading to Spain, Benét boarded a ship to Europe.

“If the moment comes when it’s the obvious right thing and somebody’s got to do it, maybe it’s going be you,” he said.

Once he landed, he headed to northern Spain to meet up with Spanish fighters and get equipped.

“We were given these awful uniforms. They were woolen, so really too hot,” he said. “I guess they were leftover winter Army uniforms or something.”

He served as an ambulance driver on the front with other volunteers — shopkeepers from Brooklyn, musicians, mill workers from the Midwest — people driven only by their beliefs and without any training.

They became combatants overnight.

“Some of them adopted the soldier’s life as if they were born to it. Fortunately, I was in pretty good physical shape,” he said. “Some of the others just had a terrible time. You had these strange experiences with guys. You know, the toughest guys you’ll ever meet — they turned out to be quite chicken. I’ve seen a guy’s hair turn white. Strangest thing in the world.”

Benét also remembered seeing Ernest Hemingway.

“The thing we liked about Hemingway was that he liked soldiers. He’d been under fire. He knew that you didn’t want to talk about it,” Benét said.

After 18 months, Benét and many of the volunteers left Spain. They knew that with support from Hitler and Mussolini, Franco’s soldiers would win. But Benét says it was tough to go.

“You became so close to the Spanish people that you thought, ‘I ought to stick around,'” he recalled. “Some of them went to the mountains and said ‘OK, I’ll live and die here.’”

Back in New York, Benét continued writing about the war for leftist magazines and Tass, the Soviet press agency. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade vets also organized public talks.

“We tried to explain — sure, you’re not interested in politics but politics is going to be interested in you,” he said. “Even young men who were going to be drafted, a lot of these guys just didn’t have the faintest idea what was going on. They didn’t see it.”

Some of the vets, including Benét, were viewed with suspicion, especially after Soviet leader Joseph Stalin formed a pact with Hitler in 1939.

“There were the people who disliked the Russians anyway,” Benét said. “So they said, ‘Aha. This just shows you what rats they are.’”

Benét rejected the Soviet-Nazi pact too. But he was also dismayed the U.S. had left Spain to fend for itself while the Soviets backed Spain’s anti-Fascists.

After their time in Spain, Benét and his fellow vets were labelled as Communist dupes. During the Cold War, they were called to testify before Washington groups, like the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

But Benét says he’s never regretted what he did back in the 1930s.

“I always felt that I was on the right side of history in Spain.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!