South Africa: Rationing by Committee

In South Africa, the government puts limits on life-sustaining kidney dialysis, and that puts medical professionals in a difficult position. They are tasked with deciding who lives and who dies.

This is the story of two patients—and the committee that determined their fates.

In late August, Amos Phillips, 41, arrived by ambulance at Tygerberg Academic Hospital near Cape Town. His kidneys had failed. He was confused, struggling to breathe, and desperate enough to ask doctors to end his life.

Karen MacPherson, 43, was also treated at Tygerberg that month, and she desperately wanted to live. A widow with three children, she said she had been plagued by high blood pressure, a risk factor for kidney disease, since her children’s birth. “It’s because of the high blood [pressure] the kidneys don’t want to work anymore,” she said.

More than 200 new patients a year seek treatment at Tygerberg Hospital for severe, chronic kidney failure. The condition can come on suddenly and affect anyone.

Some forms of kidney failure are partial or reversible. Others are permanent and fatal without treatment.

To live, both Amos Phillips and Karen MacPherson would need ongoing dialysis treatment to filter toxins from their blood. But needing treatment didn’t mean they would get it.

“It is an extremely expensive disease to treat,” said Dr. Rafique Moosa, a kidney specialist at Tygerberg Hospital and head of the Department of Medicine at the University of Stellenbosch. He estimated that putting a patient on dialysis costs about $10,000 per year.

“Now, for our economy, that is really a substantial amount of money to spend on a single patient,” he said. “There are other major health challenges and priorities that we as a society face.”

To save money, public hospitals in South Africa strictly limit the number of dialysis treatment slots. It falls to the medical staff to ration.

The Committee

A committee meets at Tygerberg Hospital on Tuesday mornings to decide who will be accepted into the dialysis treatment and transplant program. The odds for new patients are not good. When the program is full, only about one in five is accepted for the program.

On a recent Tuesday, around a dozen medical professionals wearing stethoscopes around their necks gathered in a small conference room at the hospital. The list of patients to be discussed at the meeting included MacPherson and Phillips.

The question of how medical professionals choose who lives is particularly important given South Africa’s history. Tygerberg was built during the apartheid era, when the government mandated racial segregation. The vast hospital has hallways that stretch out east and west, in wings that are mirror images. One side used to treat white patients. The other treated nonwhites.

For decades, a committee at the hospital has decided who gets dialysis treatment. In a recent study of historical data from Tygerberg’s program, Moosa found that patient selection often fell along racial lines. “What we clearly discovered in that initial paper was that black patients were disadvantaged,” he said.

The apartheid era ended with the first multi-racial, democratic elections of 1994. However between 1988 and 2003, Moosa’s study found, white patients were nearly four times more likely to be accepted for dialysis treatment than nonwhites. During that period, there was little in the way of detailed guidance governing the selection process. That left patients and the public with limited insight into the basis for the committee’s decisions.

A recent effort has aimed to change this. Several years ago, the government announced cutbacks that would further squeeze the dialysis program. At the same time the number of new kidney patients was skyrocketing due to a growing rate of diabetes and other risk factors.

Moosa protested the budget cuts and sought to have government officials take more public responsibility for rationing. That meant working with them to establish government-approved guidelines for patient selection—essentially a more standardized and explicit rationing system. Ethicists and several patients with kidney disease also provided input.

“The main thrust of this was to be fair and equitable and transparent,” Moosa said. The provincial government adopted the new system earlier this year. It categorizes patients based on a variety of medical and social factors.

This was the system that would be used to evaluate Amos Phillips and Karen MacPherson, the two recent patients at Tygerberg.

Weighing the Factors

At the committee meeting, the hospital’s longtime social worker for kidney patients, Marietjie Swart, presided. She projected a photo of Phillips onto a large screen.

The image showed a man with closely cropped brown hair lying in his hospital bed.

Phillips’s doctor outlined his medical condition, and then Swart reviewed other aspect of his life that might have a bearing on the committee’s decision. She began with his age and where he lives. “He can read and write,” she said. “He speaks Afrikaans and Xhosa, as well.”

Committee members listened for the factors they’re supposed to consider when deciding whether to accept someone for the dialysis program.

Phillips “never smoked, never used any drugs,” Swart continued. “He only drank over weekends with his wife, but they would only buy about four bottles, 750 ml., between the two of them.” Phillips was, Swart said, “not a party animal.”

That was a point in his favor. Under the guidelines, active substance abuse automatically excludes a patient from receiving dialysis.

Swart also discussed Phillips’s living conditions. “It’s a one bedroom house, with a lounge, kitchen, and a bathroom,” she said. The bathroom had a tub, sink, and a toilet.

The guidelines call these “good home circumstances,” and they, too, improved Phillips’s chances of being chosen for dialysis. Doctors say having running water, sanitation and electricity is helpful for a certain type of dialysis performed at home. However, these criteria disadvantage the poorest South Africans, who often lack utilities at home.

Swart offered more personal details. “He is employed on a farm,” she said. “His income is more or less 1,200-1,500 rand a month.” He had “no criminal record” and was married to a 33-year-old woman. “They’ve got three children of 13, 9, and 4 years old, all three living with them.”

These factors—criminal and employment history, whether the patient is a parent—have little to do with the chances of benefiting medically from dialysis. They are, instead, a measure of social worth.

Dr. Moosa says the committee used to weigh these factors heavily when considering patients for dialysis. “I suppose we used a utilitarian approach,” he said. “The question that we used to ask ourselves—you know, if we put this patient onto our program, of what benefit can he be to the society?”

Today those factors are supposed to be given less weight. The ethicists who helped draw up the guidelines argued that medical practitioners should not judge which patients are the worthiest contributors to society.

Judgments are often wrong. For example, former prisoners might have been falsely convicted, especially during the apartheid years. Patients who lack their own children might be helping to raise others.

Most important, the ethicists said, are medical criteria. Is the patient healthy enough to undergo a kidney transplant? If so, he or she might someday no longer need dialysis, and that would free up a slot for a new patient.

The problem is, few actually are able to get transplants. There are far more good medical candidates than there are dialysis slots. Therefore, the committee falls back on subjective criteria—does the patient seem motivated? Does he or she have a good social support network?

The assessment committee weighed the factors in Amos Phillips’s case. They had to decide whether he should be ranked “category one,” the only category of patients guaranteed dialysis.

“I think he would almost be a category one patient if it wasn’t for his late presentation,” Moosa said to his colleagues at the committee meeting.

By “late presentation,” Moosa meant that Phillips had arrived at the hospital after his kidneys had already failed. He needed to be put on life support, with a breathing tube and emergency dialysis until he was stabilized. That bumped him to category two—not guaranteed a spot in the chronic dialysis program.

The Case for Karen MacPherson

The same day, the committee members also talked about Karen MacPherson, the widowed mother of three.

Her picture was projected on the screen. Her wide eyes peered at the camera through large plastic glasses. Dr. Yazid Chothia described her medical and social situation.

“She’s the only breadwinner,” he said, and she had been raising several children. Now other family members were caring for her. “Yesterday they brought her in here because she was nauseous, vomiting,” Chothia said. “It sounds like the family is struggling in terms of taking care of her.”

MacPherson’s case had come before the committee before. She had many characteristics that counted in her favor.

She was well below the age of 60, the cutoff for initiating dialysis under the guidelines. She didn’t have any other serious medical or psychiatric disorder, which could disqualify her. She had a home near the hospital with running water and electricity.

Before the new guidelines were adopted, the selection committee might have given great consideration to the fact that she was a mother with a steady job and no criminal history. But the committee had recently turned her down.

“We didn’t accept her for the program?” Moosa asked his colleagues. He had been on vacation and wanted to know why.

“It was mainly based on her BMI, prof,” Chothia said. “Her BMI was 39.”

BMI is body mass index. MacPherson’s was high. She was obese.

Although obese patients do better than average on dialysis, they have a poorer prognosis when it comes to kidney transplant. That, according to the new rationing guidelines, takes precedence.

Moosa accepted the committee’s previous decision. MacPherson had been assigned to category three—automatically excluded from dialysis treatment. She was already very sick.

“It probably won’t be for very much longer,” Moosa said. “Shame.”

The committee members took some steps to help her. They agreed to provide a letter that could be used to relieve a debt. They also referred her to Eagle’s Rest, an inpatient hospice located on the grounds of an evangelical church.

Grasping for Hope

The next day, MacPherson lay in bed at the hospice beneath a pink blanket. She trembled when she sat up. She was too nauseous to keep down her food.

Her father came to visit, and she asked him about her prognosis. “Did the doctor tell you how much longer I’ve got to live?”

“You’re going to live long enough,” her father, Richard MacPherson, answered. “Don’t you worry about that. You just get well. That’s all.” He smiled at her. “There’s no limitation. The doctor can’t say that.”

With her family’s support and the nurses’ prayers, Karen MacPherson tried to stay hopeful.

“I want to get better, I want to get out of here, get my life back on track—get back to my kids,” she said. “My daughter needs me.”

As she spoke, she seemed unaware that she had been turned down for dialysis, or even that dialysis could help her. Her doctor later confirmed that he didn’t tell Karen MacPherson about the program, although he said he informed her father.

According to the prioritization guidelines, patients are supposed to be fully informed of the committee’s decision and the reasons for denial, and given the opportunity to appeal.

But Dr. Rafique Moosa says despite the need for transparency in the new rationing system, being completely open is sometimes just too hard.

“The reality is that it’s very difficult to go to a patient and inform them, well look, there is this particular form of therapy which is available to you which will help you live another reasonably healthy life for another five to ten years, and then in the same breath say, well, unfortunately I can’t offer it to you,” he said. “I think it’s actually cruel to dangle that almost as a carrot in front of the patient.”

Local and Global Inequities

Perhaps even crueler is the fact that dialysis is rationed only in the public system, where about eight out of ten South Africans get their care. Patients who have medical insurance or who are wealthy enough to pay for treatment out of pocket can get dialysis at private clinics regardless of their age, most medical conditions, or social situation.

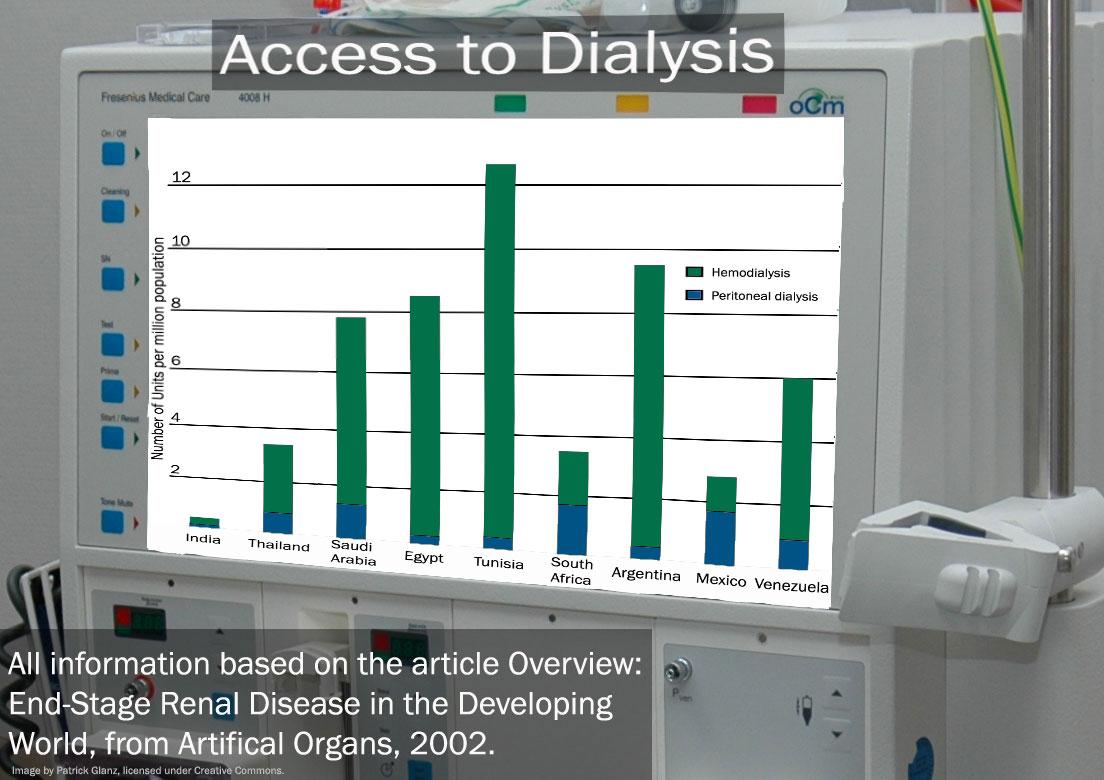

That inequity is mirrored in the larger world. In many countries, the vast majority of patients with kidney disease don’t have access to dialysis. In the United States, however, virtually all do.

Back in the 1960s, U.S. health professionals quietly rationed dialysis—much as South Africans do today. But Americans were so outraged when they learned about rationing based on perceived social worth that Congress eventually passed legislation that now provides dialysis through Medicare for patients of any age. It’s a massive program that costs US taxpayers around $20 billion a year.

South African physicians are looking to expand public dialysis programs by partnering with private clinics, campaigning for more funding and trying to cut costs. Still, any such plans will come too late for today’s kidney patients. Tygerberg Hospital has no free slots for dialysis.

Sometimes, however, even strict rationing has its wiggle room.

The day after the committee meeting, Dr. André Nortje went to the bedside of kidney patient Amos Phillips. “Mr. Phillips, we discussed you yesterday in our meeting,” Nortje informed him.

The committee had classified Phillips as a category two patient. Currently only category one patients are supposed to be accepted for dialysis and the chance of an eventual transplant.

But Phillips was borderline. The committee members hate turning anyone away.

They had accepted him for dialysis.

“We decided at our meeting yesterday morning that we will support you in terms of that,” Nortje said. “What I mean by that is that we will offer you, in future, a kidney transplant.”

Phillips looked up at the doctor from his hospital bed. “Yes. I understand.”

“You understand?” Nortje asked.

“I understand and am very happy.”

Phillips began receiving regular dialysis and soon returned home to his family.

Meanwhile, Karen MacPherson only grew weaker, more nauseous and confused. Two weeks later, she was buried—on what would have been her 44th birthday.