What do the words mutton, sheep and robot have in common? Translation!

Two translators on a ship are talking.

"Can you swim?" asks one

"No" says the other, "but I can shout for help in nine languages."

Okay, not the best joke, and even though translation won't exactly save you from drowning it is something that is all around us and that impacts our lives in many ways.

Okay, not the best joke, and even though translation won't exactly save you from drowning it is something that is all around us and that impacts our lives in many ways.

Over the next few weeks we'll be exploring what translation is all about in a series we're calling "In Other Words."

If you go by what's in the Bible, we've been in need of translators since the Tower of Babel. And this need has given rise to a whole host of interesting ideas — both real and fictitious — of how to better communicate with one another.

Remember the Babel fish? That small, leechlike fish that you stick in your ear and instantly translates any language. If only, Douglas Adam’s invention from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy did exist.

“Is that a fish in your ear? Well no, it's not, it’s a translator,” said David Bellos, translator and author of Is that a Fish in your Ear? “There’s something going on that is very clever but it’s not magic.”

Oral translation or interpreting is as old as language itself. Humans have always spoken different languages and there’s always been a need for a middle man or a go-between. However scholars have actually pinpointed a starting point for written translation.

Writing arose around 5000 years ago but it wasn’t until about 2500 years ago that anything like a translation came into existence. The two first examples of translation occurred right around the same period.

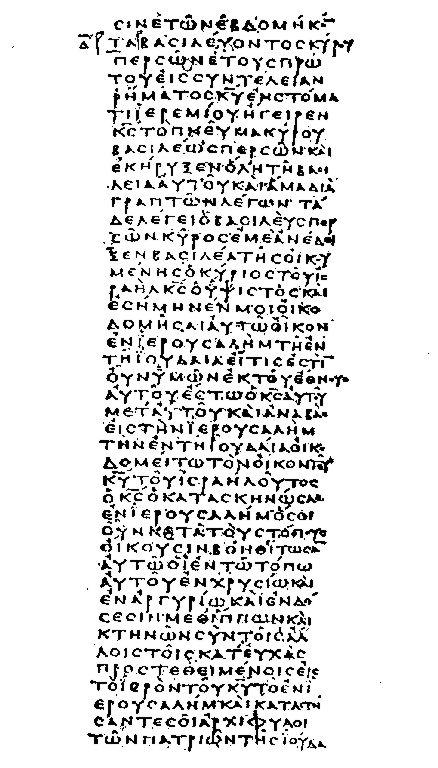

In the middle of the 3rd century BC, a community of Greek-speaking Jews in Alexandria, Egypt, which was then a Greek speaking city, translated the Torah into Greek. That translated text is called the Septuagint.

“There are lots of myths and legends surrounding it but there are no surviving texts of the Old Testament that are older than the Greek translation,” Bellos said.

There are different accounts of how this translation came to be, according to Bellos. In one story Ptolemy II, adding to the great Library of Alexandria, sought to collect every known book in the world and commissioned a translation of the holy book of the Jews.

Another story is that the Jews of Alexandria had lost touch with the language of the bible and actually needed the bible translated into Greek.

“A bit like American Jews now,” said Bellos, “not very many American Jews really can read the Torah in biblical Hebrew.”

Meanwhile within a few decades of the creation of the Septuagint, across the Mediterranean in the southern part of Italy, a Greek-speaking slave, Livius Andronicus, was commissioned to translate Homer’s Odyssey from Greek to Latin, launching, according to Bellos, the classical tradition.

“In a way you could say that translating of Homer is the beginning of an invention of the literature of Latin,” Bellos said.

“In a way you could say that translating of Homer is the beginning of an invention of the literature of Latin,” Bellos said.

So, Hebrew was translated into Greek, Greek into Latin, but what impact has translation had on English?

“English was made by translation — translation from Latin and above all translation from French,” Bellos explained.

A huge number of words came into English in the mash-up of the French the Normans spoke and the Anglo-Saxon the people spoke.

“And so English often has two words for the same things — one of French origin and one of Saxon origin, like, for example, sheep and mutton,” Bellos said. “Sheep is what the peasants looked after and mutton is what the masters ate.”

Mutton is the French word and sheep is the Germanic, or Saxon.

“We’re constantly translating between these two as we speak English and navigate the different registers of language that are more or less French depending on how high or low the register is,” Bellos said.

An example of one word that came to English purely through the translation of literature is “robot.” “Robot” is actually a Czech word and it came into English in the 1930s through the translations of the Czech writer Karel Čapek’s science fiction novels and plays. The word “robot” actually means “worker” in Czech.

Besides being a linguist, Bellos has been a longtime translator of French literature. And while he doesn’t quite believe that translation is a calling, the relationship between a translator and an author is a special one. For one, unlike the reader, a translator can’t skip over the boring parts of a book. A translator becomes intimately familiar with every single word.

“In a way the translator of a new book knows that book better than anybody else and that’s a great privilege and a great pleasure,” Bellos said.