Fixers are a foreign reporter’s best friend — and often their lifeline

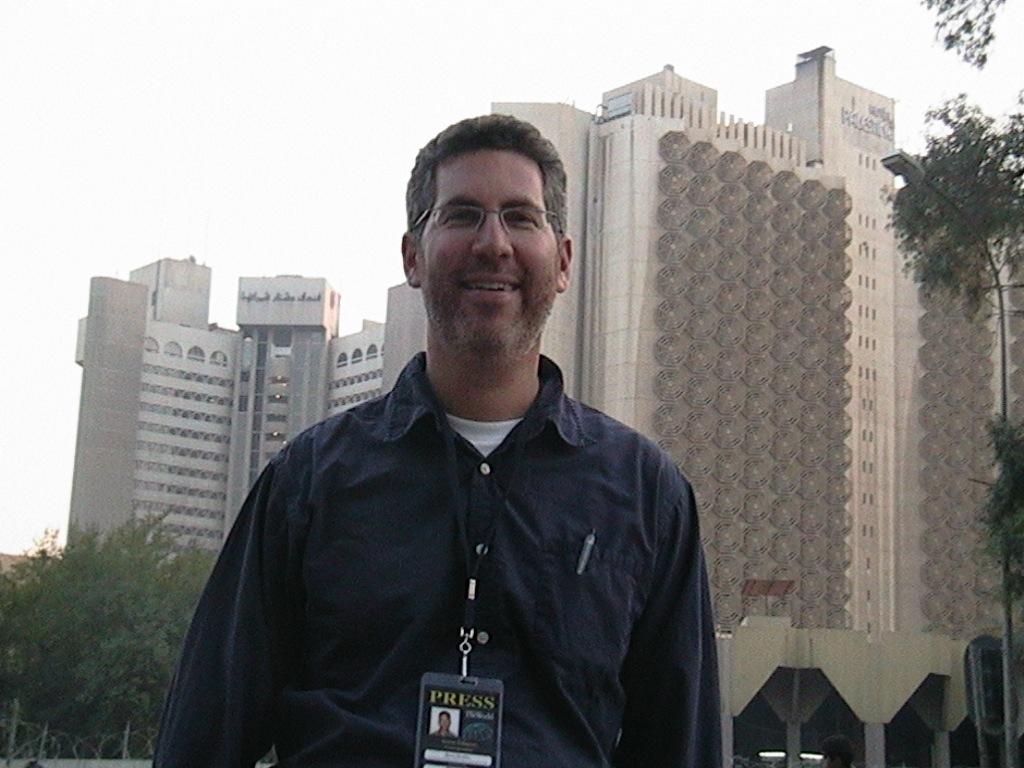

Translator extraordinaire Ayub Nuri on the right, along with reporter Aaron Schachter and their driver Abdulrazzaq Zanjeel at a street cafe in Baghdad in 2003.

Here's a dirty little secret of foreign correspondents: We don't do our own stunts.

Save for the linguistically-talented few — the late, great Anthony Shadid being among the most renowned — most foreign correspondents work in countries where we don’t know the language, let alone local customs, organizations or personalities.

So “fixers” and translators, often the same person, are vital to the work we do. Aside from a passing voice on the radio, you’d likely never know they exist.

I spent eight years reporting from the Middle East with the help of fixers. They translated interviews for me from Hebrew, Arabic, Farsi, Kurdish and Turkish. But just as importantly, they guided me through cultures that I couldn’t possibly have understood without their help.

Ayub Nuri was one of the most memorable — and the most fun.

I can’t remember our first meeting for sure, but it must have been in the bustling lobby of Baghdad’s Sheraton hotel. The towering hotel was trendy in the 1980s, but much less so by the time foreign journalists, US military types, NGO workers and dignitaries rolled in after the 2003 invasion. It turned out the hotel had been disowned by the Sheraton chain soon after the 1991 Gulf War — yet it still sported all the logos, including Sheraton placemats in the lobby cafe.

Ayub looked to be about 20 years old. He was giggly and impish; I wasn’t in the mood for giggly and impish. It was July in Baghdad, meaning the temperature tops 100 degrees in the shade. I was sweating more or less nonstop, even in my supposedly air-conditioned hotel room.

And I was fairly terrified to be in a war zone.

It was not an auspicious way to begin my six weeks in Iraq.

But the thing about being anxious at work is that it helps to work with someone giggly and impish, especially someone like Ayub, who also possesses an incredible command of history and culture — not to mention a duffel bag full of Agatha Christie novels.

Like the soldiers we often covered, a good amount of journalists’ time in Iraq was spent waiting. Or travelling somewhere to wait. It turns out the novels of Agatha Christie are a good antidote to the boredom.

Ayub helped me understand how greetings are done in Iraq; the proper way to conduct myself in a restaurant — grab table, beeline for the bathroom to wash hands, then eat communally; and about a culture traumatized by life under a despotic ruler. When you have to keep your mouth shut and disguise your feelings for decades, it isn’t natural to open up when a foreign reporter shoves a microphone in your face. Coming from a culture of confession like the US — or Israel, where I was living — there was quite a culture shock.

Perhaps the most incredible thing about Ayub was that he could talk himself into or out of any situation in a half dozen languages, including my native tongue. I don’t think we ever faced grave danger together, but I know that he’s worked with others, including our reporters from The World, where the decisions he made literally meant life or death. I was jealous of his ability.

Once, in the Kurdish area of Iraq where Ayub is from, our car was stuck in a traffic jam. Ayub told the driver to race down the opposite side of the street to get around the cars. It worked, but when we got to the next intersection a traffic cop ran up to the window and started screaming at us.

Instead of apologizing, Ayub started screaming right back. The cop got into our car, and when I asked Ayub where we were headed he said, “to the police station.”

“Aha!” I exclaimed to Ayub, triumphant. “Busted. You’ve finally been caught out. The first time.” Ayub just smiled.

When we got to the police station, the officer got out of the car, waved goodbye and wished us a nice day. “What happened?” I asked.

“I told him the reason we had to drive down the wrong side of the road was because instead of doing his job as a traffic cop, he was sitting on his behind, drinking tea and smoking," Ayub says. "And I said we’d be perfectly happy to go with him to the police station so I could explain to his superior what an awful cop he is.”

Once again, Ayub had saved the day.