‘We are helpless’: Protesting farmers in India pose challenges — and demands — to Modi

On a hot afternoon in March, hundreds of farmers gathered in an open field in Delhi, India’s capital.

Some sat in groups, listening intently to farm union leaders making speeches on a small stage. Others burst into angry chants. Their anger is laser-focused on one man: Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“We are sitting here because we are helpless,” said Azad Singh, a farmer from Haryana, a state neighboring Delhi. “Our harvest is ready in the fields, but we are here out of helplessness.”

Farmers have emerged as one of Modi’s loudest critics in recent years.

In 2020 and 2021, hundreds of farmers camped out on the borders of Delhi to protest against new legislation that they feared would hurt their incomes They eventually won — Modi made a rare concession by taking back the controversial laws, and the farmers returned to their fields.

But in February, hundreds of farmers, mainly from the northern Indian state of Punjab, began marching toward the capital, Delhi, with new demands for legal price guarantees and higher rates on crops.

The police stopped the group 125 miles outside the city, ending in clashes that led to the death of one person. The farmers have not been allowed to hold protests in Delhi, but farmer groups were allowed to hold a one-day mega rally in Delhi.

Two-thirds of India’s population depends on agriculture, but farmers are also among the poorest in the country. Rising debt, price fluctuation, and crop loss due to climate change have hurt farmer incomes.

‘Minimum support price‘

“Modi betrayed us,” said Satinder Singh, a farmer from Punjab, at the rally.

Farmers say Modi ignored a key demand to implement a minimum support price (MSP) — the guaranteed price for some crops the government sets to protect farmers against market volatility.

The system dates back to the 1960s, when India grappled with food insecurity. To incentivize the cultivation of cereals, the government introduced agricultural reforms, including MSP, essentially promising farmers that it would buy those commodities from them at a certain price irrespective of market uncertainties.

The move transformed parts of northern India, especially Punjab, into the country’s bread basket.

Economist Seema Bathla said minimum support prices act as a safety net — but there’s a catch.

The government declares minimum support prices for just 23 staples, including a range of pulses, cereals, oilseeds, jute, and more.

Due to lax oversight, only commodities procured by the government — mainly wheat and paddy— are typically sold at MSP.

Farmers want MSPs written into law and enforced better. They also want higher MSPs.

“Farming is no longer profitable, we’re barely able to make ends meet,” said Hari Singh Burdak, a farmer from Rajasthan.

Farmer incomes haven’t risen in proportion to the rising costs of cultivation, according to Bathla.

“Farming is no more remunerative for the majority of the farmers,” she said. But in her view. legalizing MSP is not an option.

“Legalization is not possible. If you legalize [MSP], private trade will not happen…then only the government will be buying,” Bathla said. Some experts say that is not feasible and could end up costing the government a lot.

MSP was a vital intervention when it was introduced, but Bathla said it has “outlived its utility.”

In Punjab, studies show that the introduction of MSP led to a focus on farming water-intensive wheat and paddy crops, which have caused severe groundwater depletion across the state.

Crop diversification is the need of the hour, said Bathla, but farmers need to be incentivized to make the switch.

Not all farmers benefit

Many attendees at the rally were Sikhs from the state of Punjab. Punjab farmers benefit most from the system, and they are the loudest advocates for the legalization of minimum support prices. In other parts of India, farmers’ struggles have little to do with MSP.

In the western state of Maharashtra, a major onion-producing region, farmers are railing against a ban on the export of onions, which has brought down prices.

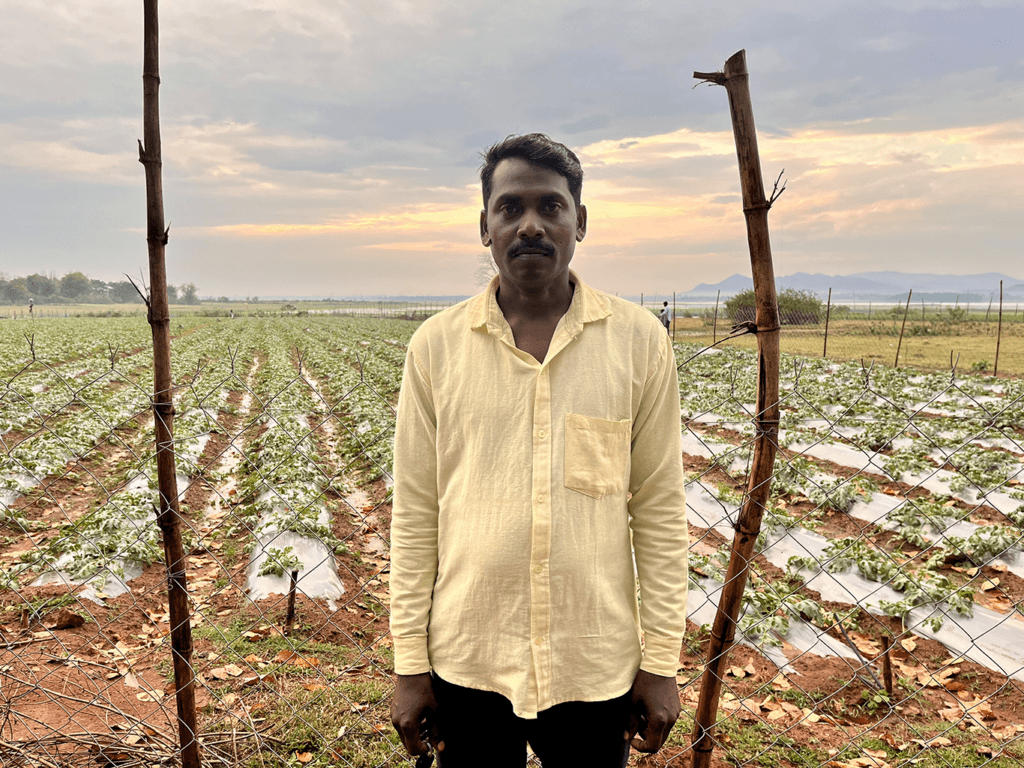

In rural Jharkhand, some 800 miles southeast of Delhi, most farmers haven’t heard of the recent protest in the capital or of MSP. Jharkhand is one of India’s poorest states. It doesn’t have sound irrigation systems, and agriculture is mostly rain-fed, so farmers can only grow crops in certain seasons.

“Farmers here have very little land,” said Nibha Devi, a farmer and community worker who teaches best practices to other farmers. “Our main problem is the unpredictable climate.”

One spell of rain or hailstorm can destroy the harvest. Farmers incur huge losses, and sometimes they just lose hope,” Devi said.

To boost incomes, the government of Jharkhand state has been helping farmers set up micro-drip irrigation systems and encouraging them to grow more lucrative horticulture crops.

Baburam Mahato, a local farmer, got his roadside farm fitted with drip irrigation in January and is growing watermelon. “I will now farm all year-round,” he said.

But when asked if he wants his son to become a farmer, he isn’t too sure.

“I hope he does something else, you can’t make much from this small farm,” he said.

Devi, the community worker, said farmers’ kids see their parents toil their whole lives but get little in return, which discourages them.

“Farming is back-breaking work. It’s not easy,” she said. “But without farmers, no one can survive.”

‘Teach Modi a lesson’

At the grounds in Delhi, a group of men sang an uplifting song to the beat of a tambourine, urging farmers to “keep up the fight, even though it is long.”

India’s general election starts on April 19 and will last several weeks.

“We will teach Modi a lesson,” said Burdak, the farmer from Rajasthan. “We made this government, we can destroy it, too.”

The Modi administration has held several talks with farmer union leaders, but there has yet to be a breakthrough. The government offered farmers a guarantee to buy five crops at MSP for five years, but the offer was rejected.

Meanwhile, Rahul Gandhi, a leader from the opposition Congress party and Modi’s biggest rival, has promised an MSP law if his party comes to power. He has said that doing so would not burden the state’s coffers.

India’s farmers forced Modi to meet their demand once. But experts say it’s unlikely he will meet their demand at this time.

And while farmers make up an important voting bloc, they are not a monolith. Political commentators say their dissatisfaction may not be enough to dent Modi’s electoral prospects.