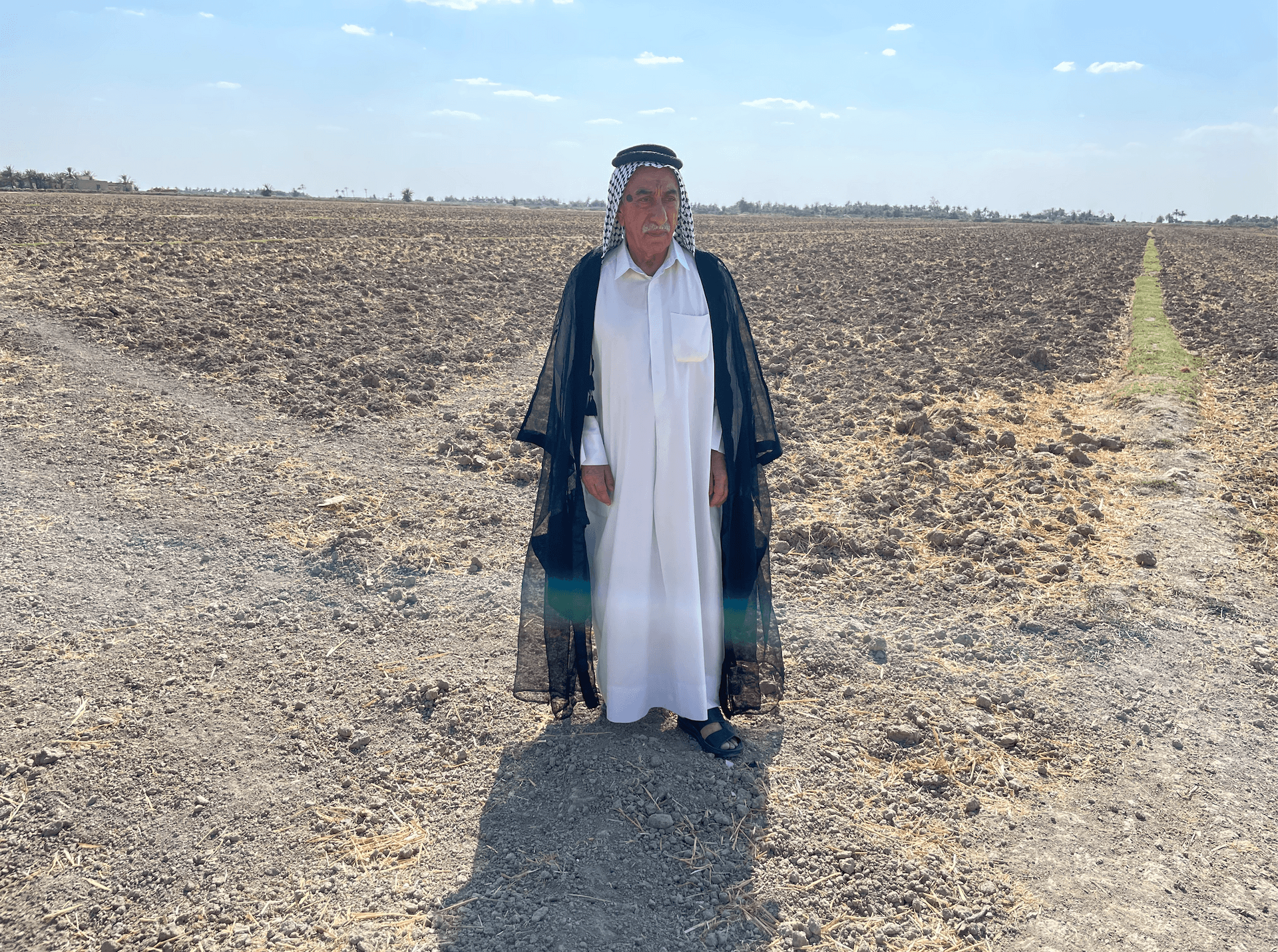

Salah Fareeq Al-Feroun and his family have been farmers in southern Iraq for generations.

In the living room of his house in al-Meshkhab in Najaf Province, his son Muhammad Ziyad takes out a photo of their 32-acre farm — located about five miles away from their home — which shows lush green grass as far as the eye can see, soaked in water.

But their farm doesn’t look like that anymore. It’s now barren and dry, with no one able to work the land anymore.

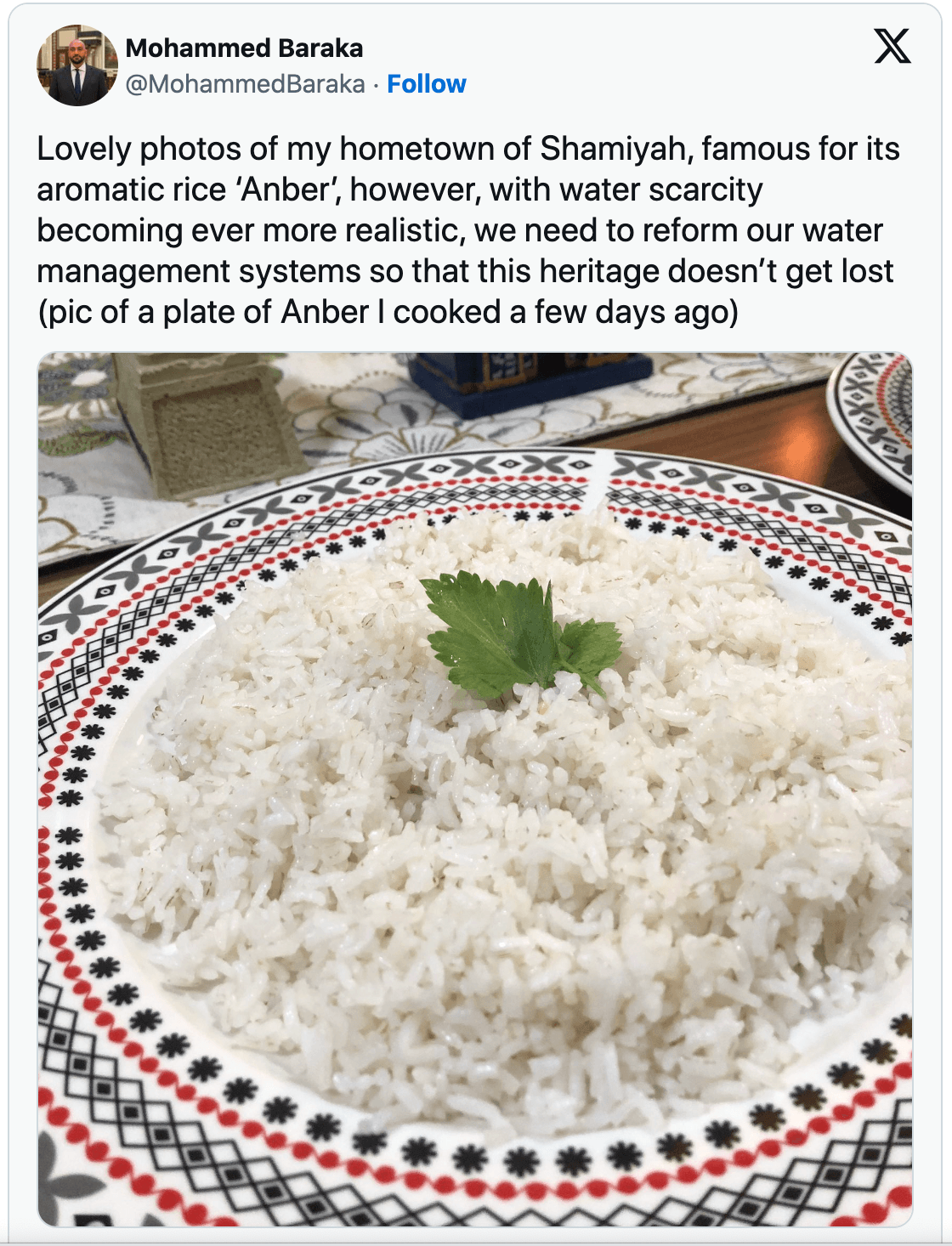

Severe water shortages in Iraq have been affecting the cultivation of the country’s signature anbar rice — Al-Feroun’s main crop. The water has been drying up because of a combination of climate change and geopolitics.

“[There’s] no rice, no vegetables, [nothing],” Al-Feroun said. “There [aren’t any plants], only wheat. This is the main river — dry.”

Al-Feroun used to grow rice in the summer and wheat in the winter. Now he can only grow wheat. Because of the water shortages, he can no longer grow anbar rice, a long-grain white rice with a high fat ratio that is unique to Iraq, and which is traditionally served with every meal. The word anbar — sometimes also written as amber in English — is an Arabic word that refers to the rice’s perfume-like fragrance.

For the past two years, though, the Iraqi government has banned farmers from cultivating the rice because it is a water-intensive crop. The paddy where the rice grows has to be fully submerged in water and takes around five months to mature. The government has only allowed for minimal farming of the crop in certain areas to preserve the seeds for future cultivation.

Importing rice

This has forced Iraqis to import rice from other countries, including Iran, Pakistan and India. The imported rice has a different taste than anbar.

“There used to be five types of anbar rice, but now there are only two,” explained Ahmed Salim, the manager of a store at Al-Warda Market in central Baghdad, as he poured out some rice into packets for weighing. “And the prices have more than doubled. We depend on Pakistani rice — Basmati.”

‘The Cradle of Civilization’

For centuries, Iraqis have relied on water from two main rivers: the Tigris and the Euphrates.

They are what gave Iraq — or ancient Mesopotamia — the titles “The Cradle of Civilization” and “The Land Between Two Rivers.”

But that land is drying up.

Achref Chibani, who is a climate journalist, says that climate change is one factor and that it has a snowball effect.

Extreme heat has also devastated crops in neighboring Turkey, which is where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers begin.

There are water-sharing agreements among the countries that surround these rivers: Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria.

Chibani says that the effects of climate change are exacerbated by poor governance and regional politics.

“The impact of climate change will make geopolitics more obvious in the near future because close coordination will not be an option, it will be mandatory.”

“It’s a combination of both, but the impact of climate change will make geopolitics more obvious in the near future because close coordination will not be an option, it will be mandatory,” Chibani said.

“And those decisions vis-a-vis projects in Turkey are affecting the quota of water in Iraq,” Chibani explained. Plus, the Iraqi government hasn’t been involved in close negotiations over regional water-sharing because it’s been preoccupied with its own internal security issues.

International collaboration

Al-Feroun, the farmer who can no longer grow anbar in his fields, agreed that climate change is a factor, but that geopolitics also plays a major role.

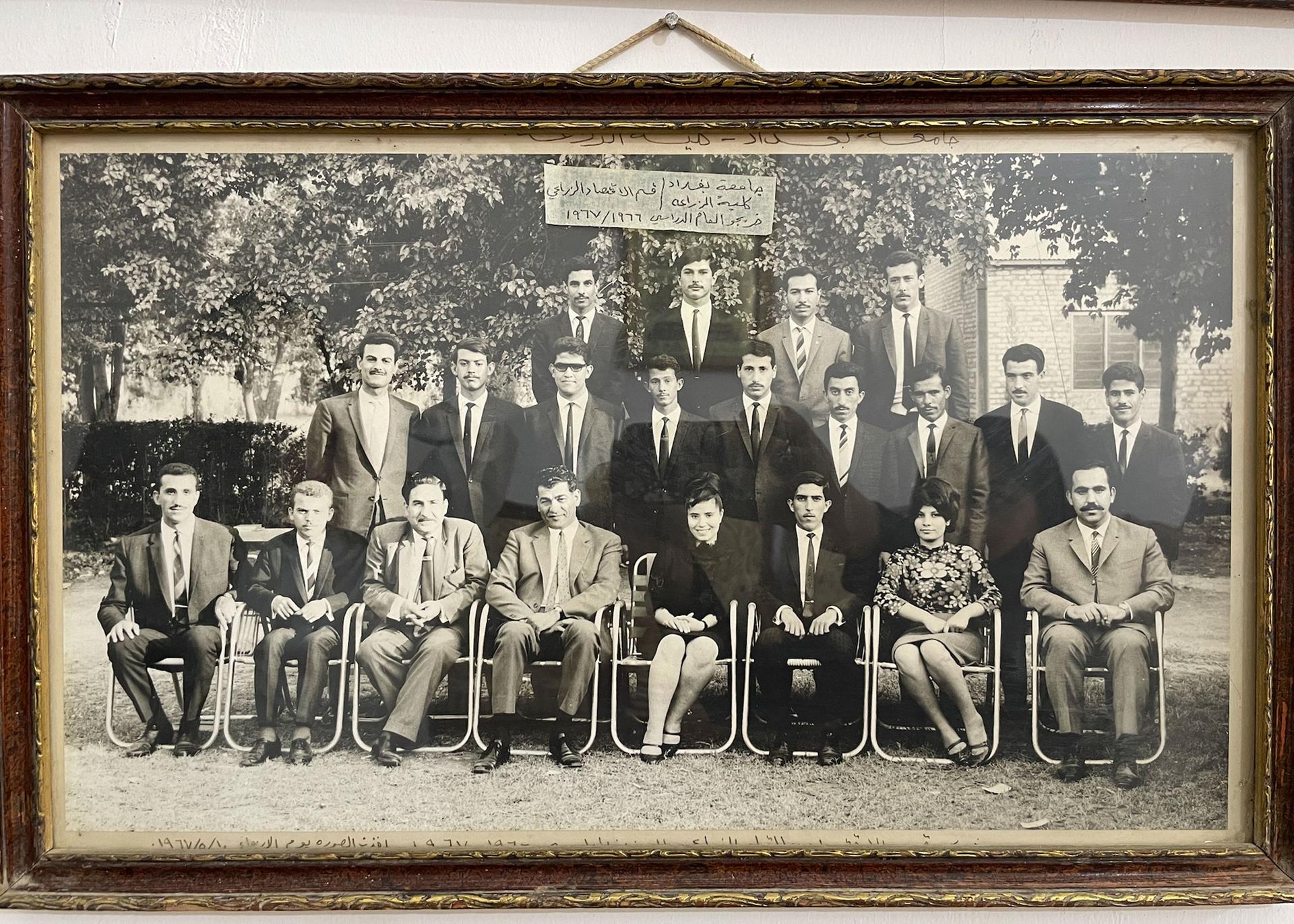

In addition to being a farmer, he spent 25 years teaching at an agricultural secondary school for the Ministry of Education, which has given him insight into how geopolitics has played into what’s happening on his farm.

Back at his home, there are large wooden cabinets filled with books and photos on the walls of his university graduation. And photos of himself, as a government employee, meeting with foreign leaders over the years.

Al-Feroun said that a government minister visited farmers recently, telling them they would be compensated for their losses, but they have yet to see any assistance. He said that the government has to move beyond making visits and promises.

“Our government has to have serious conversations,” he said, “not just with Turkey, but with the United Nations, the Arab League, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Non-Aligned Movement to get our rights.”

After generations of cultivating the fields, he hopes that his children will also have the chance to be able to continue the family legacy.

Enas Razak Ibrahim contributed to this report.

Related: This startup is fighting to keep Iraq’s palm trees alive