Swedish singer and songwriter Nea remembers inventing her own pop songs when she was just 6 years old.

Nea, who has written some of the most-popular hits performed by Swedish artists in recent years, said that dedicating her life to music didn’t seem like such a big deal growing up in Sweden in the 1990s.

Bands such as Roxette and Ace of Base were international stars, and the legacy of ABBA still loomed large.

“Having these role models was a huge factor in that I dared to approach music as a career,” she said. “I had those musicians in Sweden that I could look up to. And I thought if they can do it, I can do it.”

But Nea’s career wasn’t just influenced by Sweden’s pop icons, it was grounded in something far more fundamental: the education system. In Sweden, cultural schools, known as kulturskolan, offer free music classes where children can learn to play an instrument or sing. The schools, which are dotted throughout the country, are paid for by local municipalities.

Swedish music producer Max Martin, who has written more No. 1 hits in the US than any artist except for Lennon and McCartney, attributed the cultural schools to his start in music.

Last November, the newly elected, right-wing government in Stockholm, which depends on the far-right party Sweden Democrats for support, announced it was cutting the budget for cultural schools in half. Artists like Nea and Martin say the decision could be devastating for the future of Sweden’s music business.

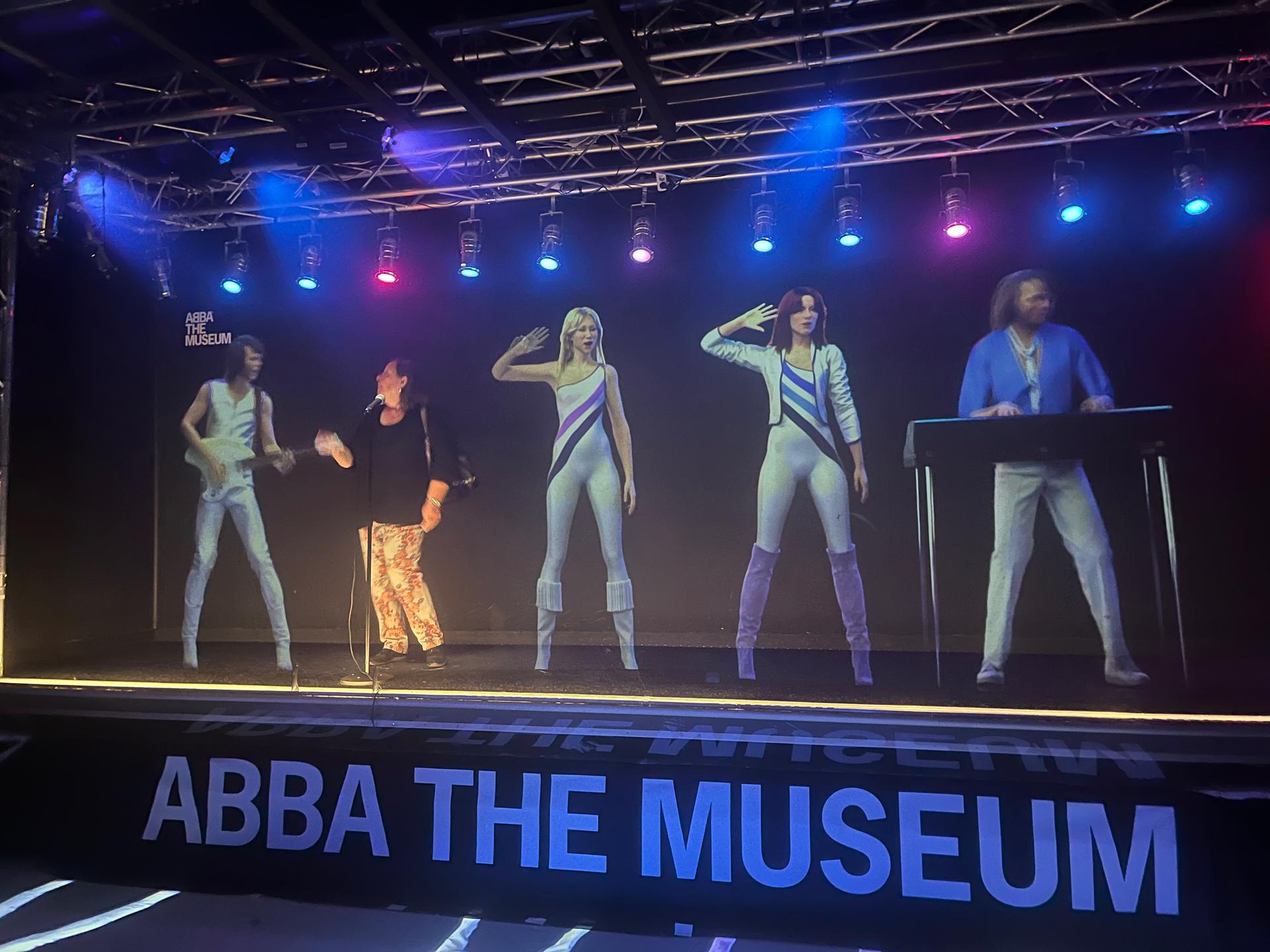

Sweden’s success in the pop music industry is nothing short of exceptional for a country of just over 10 million people. ABBA blazed a trail in the pop music field, and still today, long lines of people queue daily to visit the ABBA The Museum in Stockholm.

Producer Martin carved out a name for himself writing hits for Britney Spears, Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran and The Weeknd.

Linn Wexell, who runs record label Milkshake with her partner Petter Eriksson, said that while everyone appreciates ABBA’s unprecedented accomplishments, Martin’s success opened the eyes of younger musicians to the possibility of a different type of music career.

Singer Nea attended the music academy Musikmakarna in Örnsköldsvik, which specializes in songwriting and music production. Securing a place at the college is fiercely competitive, she said, but once you’re accepted, there are no fees involved.

“It’s not like in America where your parents may have saved money their whole lives so you can go to university.”

In Sweden, you can take a chance at a college course in song-writing and if it doesn’t work out, you’re not left with a lifetime of debt, she said.

Conductor Sofia Winiarksi also credited Sweden’s music schools for her choice of career. Winiarksi attended a choir school, another hugely popular option in Sweden, as a child.

An estimated 600,000 Swedes regularly sing in choirs.

Winiarski said when she was younger, children could take time out of school to attend music lessons and, as a result, many Swedes grew up playing an instrument or singing.

But Winiarski said that appreciation for the arts appears to have faded in recent years. Successive governments like to talk up the fact that Sweden is a world leader in pop music but artists are continuously forced to point out that this music wonder didn’t grow out of a vacuum, she said.

“There’s an ecosystem and an infrastructure that is pretty fragile, and if we start tearing down aspects of it, like the kulturskolan, we don’t know if we’ll still have this music miracle.”

Sweden’s oldest concert hall, built in 1877, Musikaliska, is facing closure because the government agency that owns the building has hiked rents by more than 60%, Winiarski said. The conductor launched a petition to try and save the institution, gathering almost 30,000 signatures.

But right now, she said it stands silent and any prospect of saving it looks bleak.

“Can you imagine if this was Vienna and the Austrian government was allowing one of its most famous opera houses to shut down?” Winiarski said. “There would be uproar.”

Winiarski and other musicians say that the current government is obsessed with students achieving higher grades in academic subjects like math to the detriment of the arts. The far-right Sweden Democrats party is more interested in promoting traditional Swedish music, Winiarski said.

Caroline Fagerlind, head of exhibitions at the Avicii Experience in Stockholm, agreed.

DJ Avicii, who was born Tim Bergling, is often credited with innovating electronic dance music (EDM). Avicii went from sleeping on friends’ couches in his early 20s to headlining dance music festivals within just a few years. His 2011 hit, “Levels,” propelled him to superstardom and he went on to collaborate with everyone from Madonna to Coldplay to Rita Ora.

Avicii took his own life in 2018 at the age of 28. The Avicii museum documents his journey, from the young teen mixing tracks in his bedroom to headlining festivals, taking home $250,000 for a single night’s work.

Fagerlind and the Tim Bergling Foundation are now calling on schools to include Avicii as part of the music curriculum. Avicii’s death is a cautionary tale about the pressures of unexpected stardom, Fagerlind said, but it’s also an important story about the mental health struggles so many artists endure. His work continues to influence music producers around the world, and young Swedes should be encouraged to learn about that, she said.

Wexell said Avicii’s work is also a reminder of how Swedes enthusiastically embraced digital technology in the music sphere. After all, Spotify was founded in Stockholm, Wexell pointed out.

Singer-songwriter Nea said that just saying you are Swedish appears to open doors in the music business internationally. Nea has written songs for many of Sweden’s most-popular artists like singer Zara Larsson and DJ Axwell as well as British rapper Tinie Tempah and South Korean pop group Twice.

In the last few years, Nea has found success as a solo artist. Her song “Some Say” has clocked up close to 400 million listens on Spotify. At meetings with music executives abroad, Nea said, she is often asked what’s in the water in Sweden that the country has managed to produce so much talent.

It’s great to know that we have this reputation within the global pop music industry, she said. But it would be nice to think our own government is as invested in supporting this great Swedish success story, she said.