A couple of weeks ago, millions of Brazilians received a text from messaging application Telegram saying that Brazil was about to pass a law that would “end freedom of expression.”

The app also claimed that the bill would give the government “censorship powers without prior judicial oversight.”

The legislation requires internet companies, search engines and social messaging services to find and report illegal material themselves, or face heavy fines.

Brazil’s Congress is debating the proposed law, which if passed, would be one of the world’s harshest laws against fake news. The bill has already been approved by the Senate and it’s now awaiting a vote in the lower house. But the “Fake News Bill,” as it’s being called, is extremely controversial.

Congressional leaders attacked the Telegram message on the floor of the lower house.

“They are spreading lies saying that the Brazilian parliament wants to approve censorship. That [it wants] to end democracy. This is scandalous,” said Orlando Silva, the sponsor of Bill 2630. “It’s a scandal that a multinational corporation wants to push the national Congress onto its knees.”

Silva added that lawmakers had specifically invited Telegram many times to participate in the debate over the legislation, but the company had declined.

Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes then threatened to take Telegram offline for 72 hours if it didn’t delete the message.

The platform finally complied. But it was a sign of just how heated the debate over this bill has become in recent weeks.

Censorship accusations

Analyst Alan Ghani, of the conservative news outlet Jovem Pan, has called the forced removal of the Telegram message: “Censorship, pure and simple.”

He added: “Would we punish a newspaper editorial, when many outlets have come out against the fake news bill in their editorials? It’s the same thing.”

But the head of the government coalition in the Senate, Randolfe Rodrigues, told the media that the platforms are very different. He said there are government regulations for TV and news outlets, and that the same is needed for social media firms.

“To the heads of the big tech companies and their shareholders anywhere in the world, Brazil will not be no-man’s-land,” he said. “You will not be permitted to do what you want here without punishment.”

David Nemer, a Brazilian media studies professor at the University of Virginia, has researched social media platforms for years.

“These platforms are not neutral,” he said. “These platforms are not just publishers. They are part of the message. And they curate the message.”

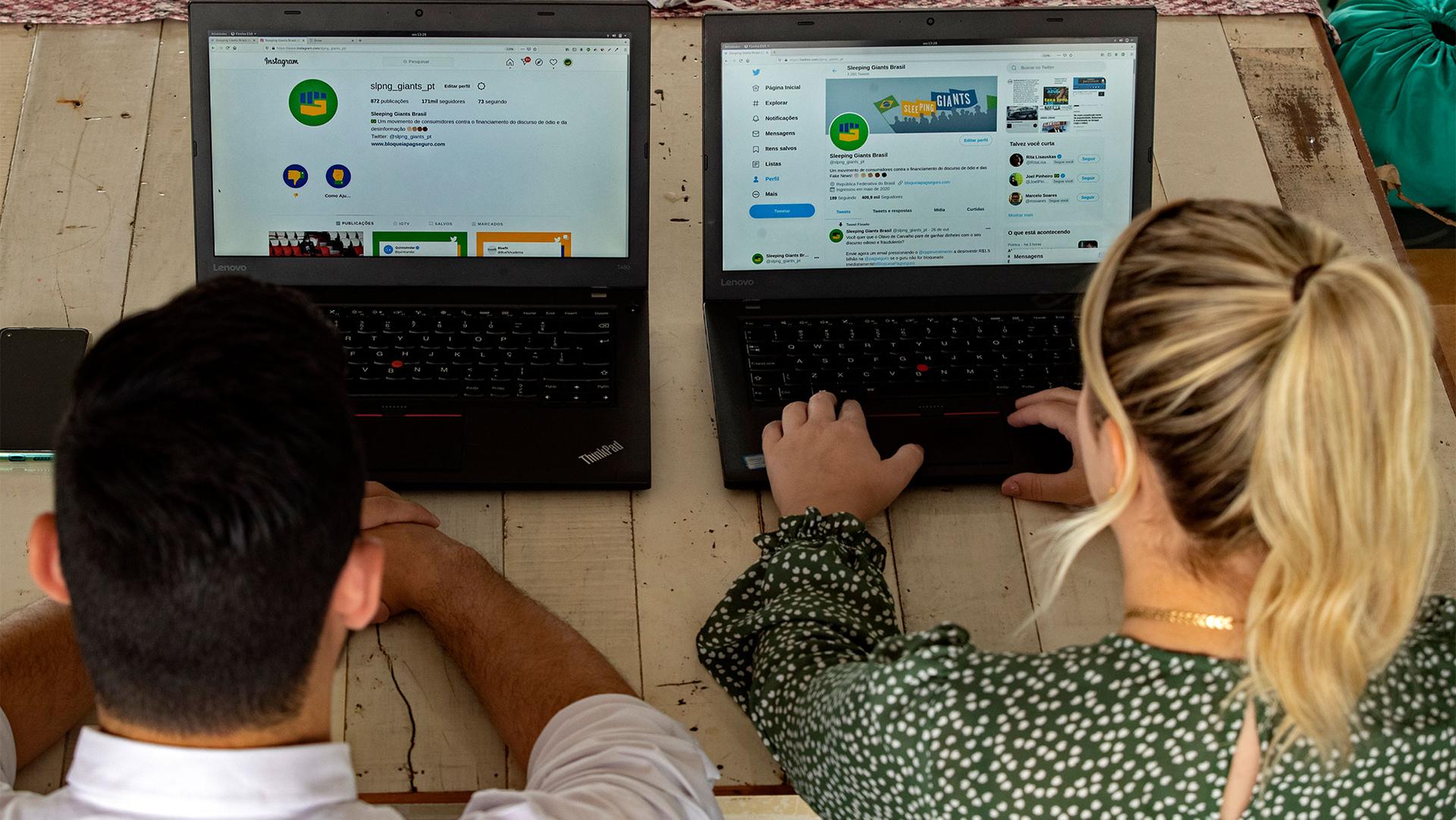

Fake news has been a major issue for Brazil in recent years.

“[Fake news] has harmed public debate,” said Luciana Santana, a political scientist at the Federal University of Alagoas. “[It’s] gotten in the way of serious discussions over public policies, and influenced political races in Brazil.”

Experts say it played a decisive role in the 2018 election of former President Jair Bolsonaro. During the pandemic, he told Brazilians that getting COVID-19 vaccines could turn them into crocodiles.

Creating transparency

But, this bill isn’t just about fake news.

“It’s more about bringing transparency, from the big techs in terms of access to the algorithm, access to reports about the algorithm, understanding how these platforms behave, so we have a more transparent way of understanding … the role of these platforms in everyday life,” Nemer said.

Brazilian journalism professor Rogerio Christofoletti said this bill is also about holding social media firms accountable when dangerous, hateful or misleading content is shared on their platforms.

“These digital platforms have the means to reduce the reach, to adjust their algorithms, to not promote specific content,” Christofoletti said. “The platforms can do more than they have. And a law like this can force these platforms to use their technical power to combat disinformation.”

Nemer added that these companies are pushing back for a reason.

“This is why the big techs are playing hardball in Brazil,” Nemer said. “Because they know that if Brazil passes this bill, then it sets the precedent and the other countries will follow as well. So, they’re trying to close the gate as much as they can so other countries will not follow suit and pass their own internet laws.”

Nemer is concerned that the bill may not find the votes it needs to pass, in part, because many politicians elected to Congress ran campaigns based on disinformation, and actually benefited from an unregulated social media.

And although the bill has already been approved by the Senate, the vote in the lower house has been postponed several times in recent weeks, as the governing coalition pushes to shore up more votes.

Related: The future of Bolsonaro in Brazil remains uncertain